What’s common between Mahatma Gandhi’s Dandi March of 1930 and the Stonewall riots of 1969? Well, both these events inspired 15 members of the queer community from across India to take part in a Friendship Walk in Kolkata on July 2, 1999 — an event that came to be recognised as the first Pride Walk in India.

Members of the queer community gathered yet again, 25 years later, at the same starting spot in Park Circus. Not only to revisit the moment that started it all, but also for the inaugural Queer Kolkata Heritage Walk, organised by gender and sexuality nonprofit, The Varta Trust.

Members of the Queer Kolkata Heritage Walk recreated the iconic photo at the same gazebo as the Friendship Walk in 1999

The queer movement in Kolkata

The Indian queer movement started in the late 1980s. However, the only events were private parties in people’s homes, and melas organised by Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee for transgender sex workers. “These parties were very underground, and even the people who did come were not very sure of themselves. There was always the risk of the police barging in,” explained Aditya Mohnot, who has been an active member of the city’s queer community since the 1990s. Apart from the parties, exchanges mostly happened at selected cruising spots like Minto Park and Park Circus Maidan. “Today, people often equate cruising with sex. But in those days, a lot of people, including me, just wanted to hang out with other queer people. We wanted to know that there were more people like us, and create a space where we could be ourselves,” he added.

An occurrence in 1998 mobilised this movement like never before. Queer activist, writer and archivist Pawan Dhall, who curated the Queer Heritage Walk, remembers it like it was yesterday. “A massive controversy sprung up around the screening of Deepa Mehta’s Fire. The queer community was enraged because of this clampdown on freedom of expression,” reminisced Dhall, who was a founding member of Counsel Club, which was one of the earliest queer support groups in Kolkata.

A major event that mobilised the queer movement in India in the late 1990s was the ban on Deepa Mehta’s ‘Fire’

In response to this controversy, LGBT India founder Owais Khan conceived the idea of a multi-city event, where people around the country would hold a small Pride March. For the Kolkata chapter, he approached Dhall. “We felt that it was time to emerge from the shadows and say that we are here, we are queer, and we are not going away,” added Dhall, who also edited India’s pioneering LGBT journal, Pravartak.

This march was inspired from both the Stonewall riots of 1969, and Mahatma Gandhi’s Dandi March. In addition to Kolkata, several groups from Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Delhi expressed interest. But as the day approached, all of them backed out due to political and organisational reasons. “We were on the fence about cancelling too, because Section 377 was a daunting reality at the time. Owais told us, ‘If you don’t do it, I will walk alone.’ Kolkata had never had an official pride event, so we decided to take the leap,” said Dhall, smiling.

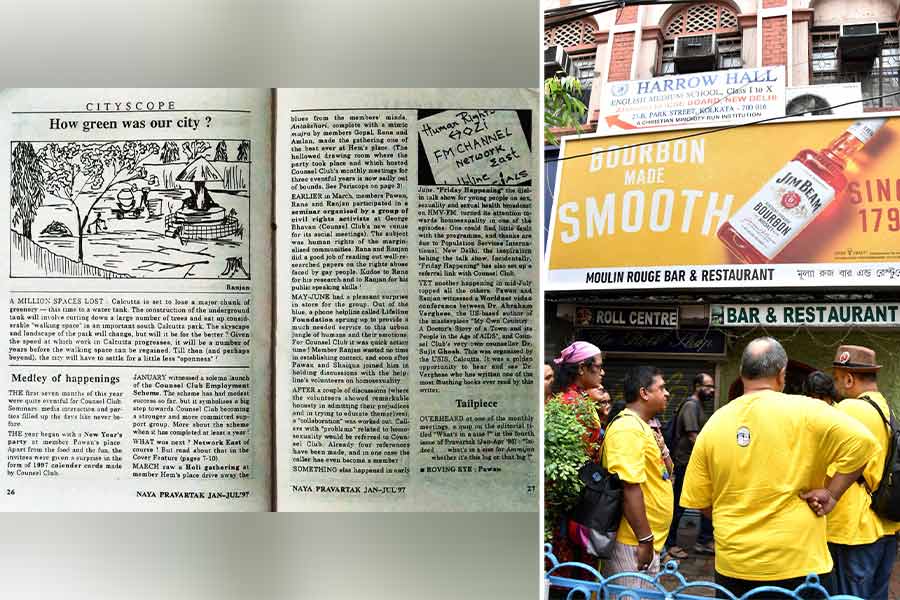

A snippet from Counsel Club’s journal, ‘Pravartak’, which was first distributed outside (right) Park Street’s Starlit Garden

The Friendship Walk of 1999

An active member of Counsel Club, Rafiquel Haque Dowjah, spoke to his contact in the police department for permissions. However, he was advised to not seek official permission, as the nature of the event would lead to Article 377 coming in. “Since we were just a small group, the contact advised us to do this in a camouflaged manner. They warned us that if we carried any big LGBTQIA+ banners, they would be forced to take action. While the cops were supportive, they just couldn’t be open about it,” Dhall added. As a means of getting the message across, the group decided to don yellow t-shirts, with a map of India and an inverted pink triangle. This triangle symbolised the markings made by the Nazis on gay people, who were to be sent to concentration camps. In the ’90s, it had become a popular symbol of the queer movement.

On the morning of July 2, 15 people gathered at the gazebo of Park Circus Maidan, about 15 short of the total number expected. They walked around the park, putting up stickers about safe sex and HIV awareness. Then, the group split into two, with one team going north and the other south. “The idea wasn’t just to make people take notice, but to have conversations with government officers, NGOs and allies. We called it a ‘Friendship’ walk because it wasn’t just about Pride, but starting a dialogue with people and organisations who weren’t friendly with us before,” smiled Mohnot. The issues raised that day weren’t just exclusive to the queer community. The group spoke about children's rights, STDs and sex workers’ wellness too.

For three years in the 1990s, the George Smriti Bhavan hosted fortnightly meetings of the queer community

After a long day, they drafted a press release at a restaurant in Park Circus, and went over to George Smriti Bhavan, where the Counsel Club used to hold its fortnightly meetings. “We had only invited six media houses because we weren’t confident. To our surprise, a dozen turned up, upset that they hadn’t been informed. They even requested us to do a ‘second’ walk outside George Smriti Bhawan to take pictures!” chuckled Dhall.

The group woke up the next day to overwhelmingly positive headlines. While congratulatory messages poured in from everywhere, Dhall believes that it took them years to see the larger impact. “Much later, people told us that while they couldn’t participate in the walk, watching us walk the streets with pride changed their lives. It encouraged a lot of them to come out to their families.”

Members of the community return to the iconic George Smriti Bhawan address

Walking down memory lane

The purpose of the Kolkata Queer Heritage Walk was to not just celebrate the iconic moment that propelled India’s queer movement to new heights, but also to introduce the younger generation to spots in the city that were integral to it.

Over two decades after the Friendship Walk, many of the original members (and some new ones) gathered at the iconic gazebo. Rain began splattering and a rainbow umbrella promptly emerged. Dhall addressed the nostalgic crowd, “Park Circus Maidan has been the starting or ending point of all our Pride Marches. It used to be one of the largest cruising zones in the city. A lot of romance brewed amongst its bushes and trees. The queer movement is equated with court cases and politics, but behind them are thousands of love stories and heartbreaks,” he smiled.

The walk commenced with a showering of flowers

From there, the troupe made its way to the George Smriti Bhavan, which hosted their fortnightly meetings for three years. Everything from the building’s brick-laden exterior to the colour of its walls remains unchanged. “Earlier, everyone used to meet in a friend’s living room in Tollygunge. Word kept spreading and the numbers kept growing. We finally had to look for a new place when 32 of us crammed in, and the landlord threw a fit!” chuckled Dhall. A community meeting by Durbar brought them to George Smriti Bhavan, and he realised that it could be a good replacement. “The monthly rent was Rs 100!”

The Drive Inn Restaurant became the hub for drafting a letter campaign against Article 377

On the way, Dhall narrated stories from his Counsel Club days, where he churned out Pravartak’s stories on a Remington portable typewriter, and printed out the first few issues from a xerox shop at Surya Sen Street. Working at a media house at the time, he realised the need for a proper layout. “I would use the computer and printer at my office to work on Pravartak, when my boss wasn’t looking,” he laughed.

As they passed Esplanade, Dhall identified several iconic spots. A Counsel Club member’s father was the manager at Paradise cinema, so people would gather at his place to play UNO and Scrabble, followed by movies. A toilet in the Maidan area was popularly known as the ‘Zigzag Toilet’, with a lot of male and trans sex workers operating there. New Empire cinema was another prominent cruising spot. People would walk up and down the arcade to ‘show themselves’. Prospective suitors would be suited in bikes on the opposite footpath. One could also purchase gay erotica CDs at Park Circus.

The evolution of the Pride Walk t-shirts, from (L-R) 1999 to 2024

The Park Street area was equally significant. Roxy at The Park Hotel hosted the first Pink Party a decade ago. Starlit Garden was a prominent spot too, with the first few copies of Pravartak being distributed outside it. “We’d normally enjoy a beer here before going to work,” Dhall joked. Towards the end of the 1990s, they shifted to Magnolia and Olypub.

Post 1995, The Drive Inn Restaurant at Middleton Street joined the list. The group drafted a letter campaign against Article 377 while meeting at its shed. The adjoining Earthcare Bookstore also became a prominent ally in the process. “Someone from our group asked the staff why they didn’t have any queer literature. The manager overheard this and invited us to stock copies of Pravartak in their bookstore,” Dhall smiled. The word spread to the point where people not only dropped by Earthcare to buy a Pravartak, but with the hope of meeting a fellow queer person.

The Earthcare Bookstore was one of the first to stock ‘Pravartak’

Finally, the walk ended with a scrumptious brunch at The Calcutta Ladies Golf Club, with a cake cutting ceremony.

Evolution since then

In the last 25 years, visibility has quadrupled, as has acceptance. The Kolkata Rainbow Pride Walk is among the largest pride marches in the country, drawing over 20,000 people last December. All of it started with the first 15 people.

“In our time, it was really difficult to mobilise people to express themselves openly. We would only find people like us at a cruising spot, or through mutual friends. In 1999, most people thought there was no one like them. A lot of groundwork has happened since, and the younger generation thankfully do not come from a place of feeling alone. The world is more connected and there is more information. It brings about a certain amount of confidence and allows people to express themselves, wherever they are,” said Mohnot.

L-R: Nitin Karani, Satish Kumar, Owais Khan, Aditya Mohnot and Pawan Dhall, who were a part of the original 1999 Friendship Walk

This has also been facilitated by the increasing number of organised spaces. Places like the Tavern behind Trincas, Porshi Qanteen and The Lalit have opened their doors and hearts to inclusivity, openly welcoming people across gender and sexual orientation. This is a sharp contrast from the clandestine meetings in the ’90s, where people gathered in someone’s home, hoping that cops wouldn’t storm in. “The community is making its presence felt, and showing the world that you can’t deny us,” Mohnot adds. He also reflects upon the Pride Month, stating how even though it is currently just a month, the lucrative economics of creating inclusive spaces and campaigns might push corporations to make it a year-long affair.

While things are looking up, Dhall does rue the lack of diversity within the community. He remembers how the Pride Walk used to be a haven for trans and gender non-conforming people, many of whom used to come from remote districts. The 2009 Delhi HC judgement decriminalising homosexual unions proved to be a turning point. “After 2009, we started seeing many more middle-class and upper-middle-class people in the marches, which was great. However, the participation from districts started declining. We must improve class and regional representation,” he said.

The walk ended with (L-R) Nitin Karani and Thomas Joseph cutting a cake to celebrate 15 years of togetherness

Mohnot agreed, adding that the division between the alphabets in LGBTQIA+ often take precedence over uniting the spectrum. He attributes this to the enduring patriarchal setup, where the cis-het white man remains the epitome of existence. “Until we accept each other within the community, how can we expect acceptance from the outside? Beyond our differences, we are the same.”

You can find more information about the Friendship Walk of 1999 on the official website.