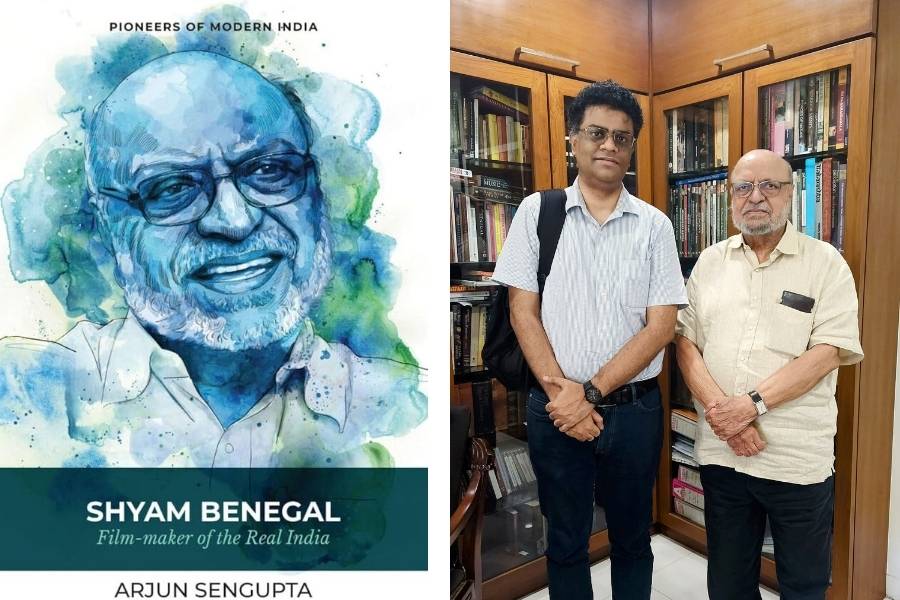

“Shyam Benegal opened up a space for serious cinema… he made films whose subjects were taken from all over the country. He was, in many ways, the first director who can justly claim that his one true subject was India — its present, its past and its possible future,” feels Arjun Sengupta, professor of English at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Sengupta’s third and latest book, Shyam Benegal: Film-maker of the Real India (Niyogi Books), was launched at the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival (AKLF) earlier in January, less than a month after Benegal passed away at 90.

A specialist in cinematic adaptation, Sengupta spoke to My Kolkata about his book, Benegal’s journey, the ideas embedded in his work, and more.

My Kolkata: Tell us about your writing process, how did you approach the subject of Shyam Benegal?

Arjun Sengupta: I did not want it to be a regular biography of Shyam Benegal. I approached it like a class, not chronologically but thematically. The book looks at not just his films, but has a separate chapter on his TV work as well — looking at the gamut of his work and then critiquing, rather than criticising.

To me, Benegal’s work seemed like something that was illustrative of what India as a country tried to be after Independence, a country trying to find its identity. And he became a kind of cinematic reporter of how this nascent post-Independence country was trying to make its way into modernity. So that was the governing idea. And then I went ahead and took up other themes, and I analysed his work in terms of those themes.

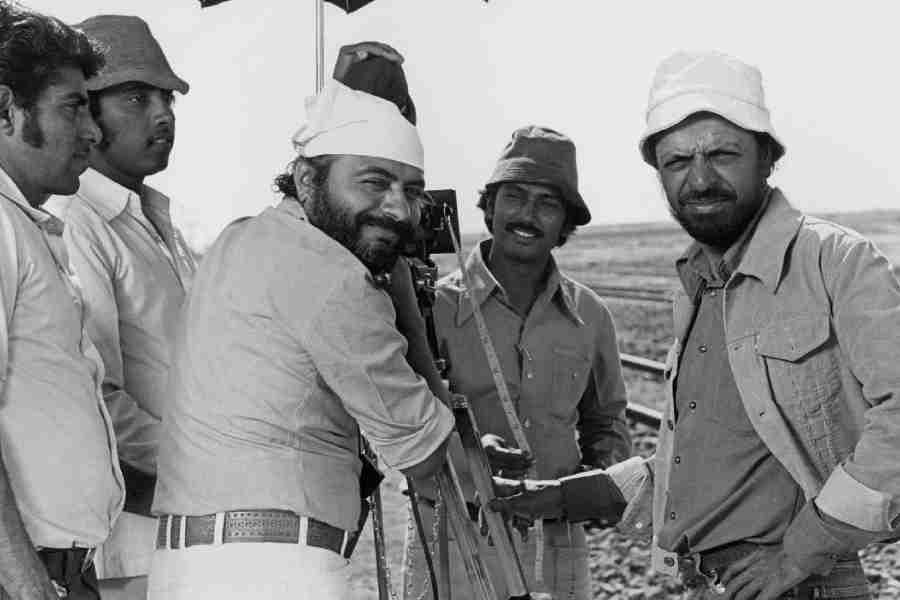

Guru Dutt had offered Benegal the role of assistant director, but Benegal refused

Benegal on the sets of ‘Manthan’ TT archives

When we look at Hindi cinema, we use the terms Bollywood and Hindi cinema interchangeably. So where does Shyam Benegal feature?

The Bollywood system was primarily escapist in orientation — a constructed, artificial time and space in which these stories would happen. While there were constant attempts to make more realistic films within the Bollywood context, whether it was Raj Kapoor or Guru Dutt, certain compromises had to be made, such as including a song. Benegal was related to Guru Dutt, and was keen to be a filmmaker from a very young age. Dutt had offered him the role of assistant director, but Benegal refused, because he simply did not want to be part of that system. He did not know what to do, but he knew that he didn’t want to do that.

After Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, Benegal saw that films could be made in an uncompromising way, which is why he did not make Ankur until he was in his late 30s.

Along the way, without deliberately doing so, Benegal created an entirely new way of making films, a new ecosystem, with bound scripts and new actors. One of them was Shabana Azmi, who transformed herself from being somewhat westernised to someone who could play a villager. Benegal’s process involved him taking his team out on location (not for dance sequences). And, because of that, all of them would live together as a family — the crew, the cast, everyone.

Decades later, when people like Anurag Kashyap do guerrilla style of filmmaking, they talk about Benegal. They take a camera and go out and make a film, and that’s something Benegal did. He pioneered what went on to become parallel cinema.

Being from advertising, Benegal already knew how to tell a story

The standout feature of Benegal’s early films was their simplicity TT archives

Was the audience for Shyam Benegal films always there, the kind that made Ankur a hit?

The audience was always there. But the mainstream filmmakers refused to believe that people wanted cinema to make them think. In the ’60s and ’70s, there was a proliferation of film societies, especially in the urban cities of India, where you would have films from Europe, Russia and the US being shown. A lot of discussions used to happen.

Benegal wanted to make a film in a regional language, but he was told by his producers to try a dialect called Dakhni (from Andhra Pradesh), which is very similar to Hindi. So that stopped Ankur from being a regional film. Being from advertising, Benegal already knew how to tell a story. When you watch films like Ankur and the first three films of Benegal, you’ll notice how simple they are. That came from his experience as an ad filmmaker — to tell the story in the most economical way possible.

Benegal believed that that art has a purpose

What was Benegal’s background like?

He grew up during a tumultuous time, when India was gaining Independence, and his family was a microcosm of all kinds of political leanings — someone from the RSS, somebody who was in the Forward Bloc, somebody who was a communist.

So, Benegal was always very serious about art. He believed that that art has a purpose, that it’s not there for entertainment alone.

Perhaps only two of his films were set in Mumbai. Tell us about his projection of the larger India, beyond the urban Mumbai/Delhi.

Most of his films were outside the cities of Mumbai, Delhi and Kolkata. I think this goes back to the fact that mainstream cinema’s representation of India was nowhere close to the real India. Benegal wouldn’t use background music, but he would have musicians singing local songs from afar. And that makes a huge point because one of the biggest elements of Bollywood is its music. And here he is, going from space to space, allowing each of the different traditions of music to imbue the space of his films, thereby telling us that India is not a monolith, that you cannot reduce the bewildering multiplicity of this country into one grand, governing narrative. Once you move away from the urban spaces, you can see the great variety that India is through all the choices that he makes.

Benegal sees through the Bollywood construct of women within the first 10 minutes

What was Benegal like when telling stories of women? In that context, do we need more female directors or more feminist directors like Benegal?

Ideally both, because there’s always the question of stories of women told by men. Benegal was always aware that he was a man telling women’s stories. He used his position as one of the leading voices of Indian cinema well, to bring to light the systems of oppression across India, not just in the rural spaces. Benegal himself was a feminist director — take Bhumika for example. He used the metaphor of playing roles in the Indian film industry to illustrate the different roles that women have to play in their lives. And if you see the first scene of that film, it opens with the camera showing Smita Patil all dressed up and starting a typical Bollywood song. The scene cuts, and immediately, we see Patil standing outside waiting for her car, and she’s wearing a regular saree. She does not have a smile on her face anymore. She’s looking grumpy. And that’s tremendously powerful. Shyam Benegal sees through the Bollywood construct of women within the first 10 minutes. She’s not always happy or always crying. She’s irritated. She is waiting in the heat for the car to come. She is constantly trying to find happiness and love, and all the men in her life reveal themselves to be hypocrites. The last scene is of her in her own space, but Benegal shows you that the space is lonely.

Today, naturally, there should be more women telling women stories, but also more feminist directors.

‘Junoon’ was a passion project and it had to be made

According to Sengupta, ‘Junoon’ was a complicated take on the role of history

What was the Shyam Benegal and Shashi Kapoor collaboration like?

Shashi Kapoor was never entirely happy with the kind of roles he had to do, because he always wanted to be an actor who would be tested and make films that would make a difference. Junoon was a passion project and it had to be made. The film didn’t give a straight answer, like British bad, India good, or India bad, British good. It gave a complex, nuanced view of this very important moment in India’s history. The people were not ready for that at the time, and they went in thinking that there was going to be a jingoistic celebration of the War of Independence, and that’s why I think Shashi Kapoor did something very useful at that point, by lending star power, influence and money, allowing him to make one of the most interesting films in this country. It was a complicated take on the role of history and how history creates narratives.

What used to be the battle for Hastinapur has now become the battle for corporate supremacy

Do you think Benegal uses mythology deliberately, or is it a part of his psyche?

For Benegal, mythology is always the foundational way in which a culture sees itself, especially the Ramayana and Mahabharata. He either uses these mythologies to tell us that the same rhythms are going on, or their essence has been incorporated into a new framework. What used to be the battle for Hastinapur has now become the battle for corporate supremacy.

On the other hand, Benegal also critiques it. In Nishant, he critiques the role of women. And in Bharat Ek Khoj, there is a particular story of Kannagi. He tells you that this is the story of a woman who gains power or is celebrated because she conforms to what a woman should be. So, at one level, he shows you that this is how we construct our idea of womanhood, but he also shows you that it is, in a way, restrictive. It rewards you, but that reward only comes through submission.

Is Benegal breaking constructs of identity in his trilogy with Khalid Mohamed (Mammo, Sardari Begum and Zubeidaa)?

Benegal was moved by what Khalid Mohamed wrote about his mother, and because that was based entirely on the idea of memory, from then onwards, memory became a core element in all his films, especially Zubeidaa. Sardari Begum is about trying to reconstruct a woman’s identity. And for Mammo, it is more about finding an identity. Post-Partition, she finds herself neither there nor here. In the end, she comes back because she gets a death certificate saying she’s no longer alive. Ironically, the only way she can be alive is by dying.

It is mostly about women in the margins. It is about women who belong to a certain minority. It is about the consequences of partition. What ties these three together is the question of identity.

Lastly, how does Benegal pave the way for future filmmakers, and also become a subject for literary or cultural studies?

Benegal inspired a great number of people, including Govind Nihalani, who used to be a cinematographer, and director Sudhir Mishra. He also allowed the likes of Ram Gopal Varma to bridge the gap between commercial cinema and serious cinema. Benegal was also full of praise for the work that is being done on streaming, like in Panchayat and Kohra.

Ultimately, in my book, I’ve tried to see how his films lend themselves to critiquing in the larger context of cultural studies. I’ve tried to look at his films as texts that can be used to illustrate the culture from which they emerged, and what they tell us about that culture within the broad framework of a post-Independent nation trying to forge its own identity.

You can purchase Arjun Sengupta’s book on Shyam Benegal here.