“Gender is like water, it can take the shape of whichever vessel you pour it into” — these are the thoughts that define Sayantani Ghosh, West Bengal’s first trans woman advocate. From school to the courtroom, and even in her own home, Sayantani’s life has been fraught with challenges. But giving up was never an option.

Last year, her life changed when she entered the Calcutta High Court as a lawyer for the first time. Outside this regal structure, Sayantani shared her story with My Kolkata.

Growing up as the ‘other’

As a child growing up in the 1990s, Sayantani had no understanding of sex or gender. Conversations around orientation were not common either. However, she always felt an attraction to things that were traditionally ‘feminine’. “While other boys played cricket and football, I enjoyed applying makeup and dressing up. Few men learn classical dance, but I trained in Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi. By the time I turned 14, I had realised that my gender assigned at birth didn’t match my psychological gender,” she says.

When she started her legal career, Sayantani faced a lot of discrimination from fellow lawyers for not being ‘traditionally masculine’

Except her mother, no one in her family accepted her. That’s where her fight began. It extended to her school, where her posture, walk and mannerisms were ridiculed. “Some of my seniors even tried to physically and sexually abuse me. I spent so much of my childhood crying, but now I understand things better. Effeminate boys are catcalled and humiliated. That’s just how society works,” she sighs.

On the family front, there were even conversations about throwing her out of the house. “I never left home, because I knew that I had to strengthen the soil beneath my feet. With education, no one has the power to discriminate against us or underestimate us. No one can question our achievements, because they are purely through capability,” she adds.

In order to empower herself, Sayantani decided to study law. She felt that if an effeminate boy became a lawyer, it would be a major win against society, and also give her the strength to break barriers and reclaim her narrative. After school, she cleared CLAT and got admission in Hazra Law College. “I was mocked there too, but gradually made friends who supported me to be who I was. Those five years in Hazra Law College saw my transformation, not just with hormonal treatment, but also in how I started perceiving myself,” she beams.

Switching paths

Unfortunately, Sayantani didn’t find a fairytale ending after graduation. While she did join Alipore District Court as a junior lawyer in 2012, the discrimination and mockery she faced from fellow lawyers severely impacted her mental health. She recalls, “The place that was supposed to get me justice, was making me question my own identity and I couldn’t take it anymore. In 2015, I left law.”

When everything was dark, it was dance that brought back light into her life. She founded the dance group, Rudrapalash, and started teaching at her home in Sonarpur, and at another space in Moulali. “Middle-class families often believe that men learning classical dance have a woman within them. I saw so many of my queer friends never being able to leave home in their dance costumes, and instead, changing into these beautiful dresses in class. I never understood this stigma, because so many of our gurus are male and Shiva’s Nataraja avatar is the very personification of power,” Sayantani says, adding that much like the concept of Shiv-Shakti, we all have masculinity and femininity within us, referring to how every individual has testosterone and oestrogen. “I believe nobody is straight. We’re all bisexual to varying degrees,” she states.

Over the years, Rudrapalash has staged dance dramas not just in Kolkata, but all over India and even in Bangladesh. Many dancers from the transgender community have been part of the performances. The flagship event of Rudrapalash is Ritu Utsav, which commemorates Rituparno Ghosh’s birthday every August 31. “Rituda always said that gender is an ever-growing and ever-changing concept, which can’t be stifled within boundaries. Ritu Utsav is a space for queer individuals, who aren’t allowed to perform at traditional spaces, providing them a stage to showcase their talent,” she says.

Sayantani’s father wasn’t supportive, but her students have instilled her with creative energy. “My family kept asking, ‘Tumi keno meye hote chao?’ But they didn’t realise, ‘Ami kemon kore achhi, seta boro kotha noy. Ami kemon hote chai, seta boro kotha’.” Sayantani beckons society to rise above the boxes it breaks people into, and see everyone as a human being first.

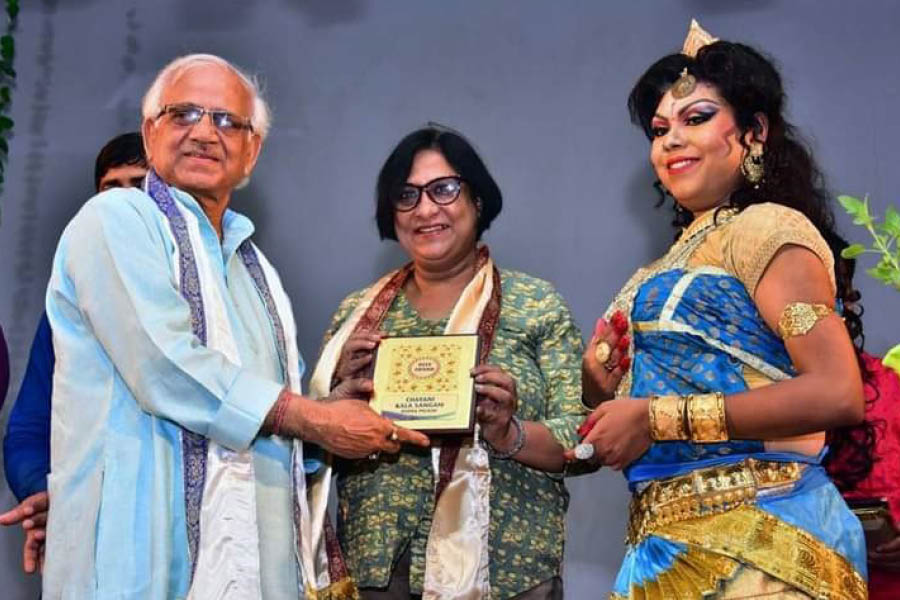

Her dance group, Rudrapalash has performed around the country

Rejoining law

In 2018, law re-entered her life, when a friend approached her with a divorce case. The recognition she received upon winning it pushed her to return to court. With her mother’s support, Sayantani completed her Masters with a specialisation in criminology and criminal psychology from Adamas University, Barasat. In 2023, she finally entered Calcutta High Court as a legal associate.

This huge feat didn’t just lead to familial acceptance, but societal appreciation. Sayantani’s face lights up when she talks about how friendly people have become, and how much respect she receives. it “When I needed people the most, I felt extremely lonely. A lot of people who would discriminate against me now want to know more about my journey!” she chuckles.

As a lawyer, divorce cases are her favourite, simply because of the poetic justice they deliver. “As a trans woman, making a man and a woman reconcile who want nothing to do with each other, feels like a blessing from god,” she says.

Her success also acquainted her with the hypocritical practices, where trans people who have achieved something in their domains are called to cut ribbons during Durga Puja and Pride Month, but forgotten for the rest of the year. “We don’t need sympathy, we want empathy,” she states.

Every August 31, Rudrapalash honours Rituparno Ghosh’s legacy with Ritu Utsav, presenting a dance drama

Despite her hectic legal commitments, dance continues to be her oxygen. Sayantani has an immense sense of gratitude for the performing art, which supported her when her degree hadn’t. When she is in court, she tasks her senior students with helping out beginners. Regular classes are held at her home, and she supervises them during the weekends. “Now that I’m in the High Court, people often tell me to give up dancing. I simply cannot do this, because it is a creative outlet that allows me to express my thoughts and feelings. I never just danced for sustenance. It was always for my mental liberation,” she says.

While there has been progress on many fronts, Sayantani maintains that three primary struggles never end for the transgender community — the struggle against family, the struggle against society and the struggle with their own selves.

She believes that sensitisation is still the need of the hour and the only way forward. For this, she has taken initiative by conducting several gender awareness workshops at prominent institutions like Surendranath Law College, Rabindra Bharati University, Jayaprakash Institute of Social Change and Syamaprasad College. “Mainstream society doesn’t realise that sex and gender are different. Sex is biological, while gender is psychological. I hope to keep fighting for grassroot awareness, even if this fight won’t be won anytime soon,” Sayantani signs off.