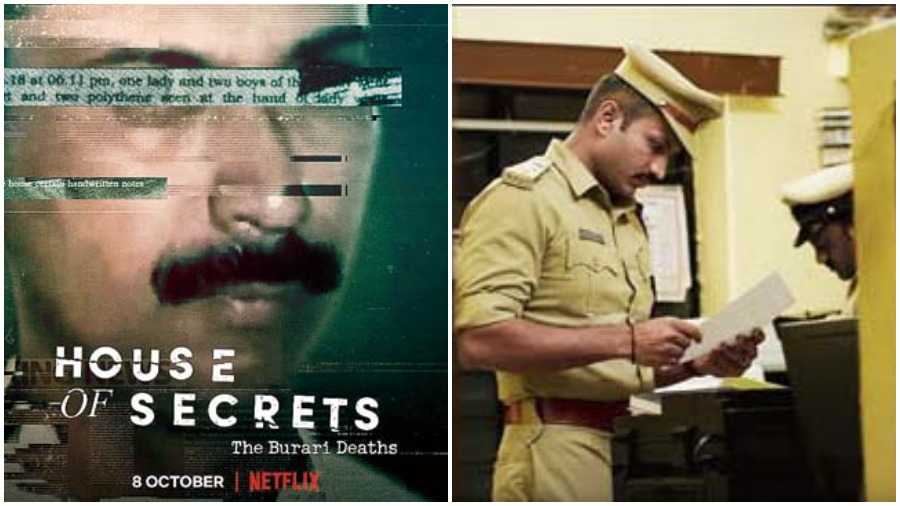

The documentary genre is well and truly taking off in India, all thanks to the boom of streaming platforms. Coming up next is House of Secrets: The Burari Deaths, a three-part docu series which focuses on the bizarre and unexplained deaths of 11 members of a family in Delhi’s Burari area, which took place in 2018 and flummoxed the nation.

Ahead of the release of House of Secrets on Netflix on October 8, t2 chatted with showrunner Leena Yadav (who has films like Teen Patti and Parched to her credit) and Tanya Bami, director, international originals, Netflix, to discuss the series and decode the documentary genre in India.

‘Why’ is pretty much redundant in this case, given the curiosity around the Burari deaths. So, how and when did the idea to make House of Secrets come about?

Leena Yadav: It was a case that got immediate attention. I was very, very curious about it, like everyone else. This happened in 2018, and in early 2019, I met the documentary team from Netflix and spoke about the case, and they were instantly interested and said, ‘Let’s explore this.’ That was the time India was getting into documentaries and I actually started shooting this series on July 1, 2019, which was the first anniversary of the Burari deaths, and I ended up shooting for 11 days. That was just the beginning of this crazy but amazing adventure of making this series.

Tanya Bami: I joined Netflix in 2019 and walked into such amazing titles that were being created, from House of Secrets to Crime Stories: India Detectives and even Bad Boy Billionaires, back then. It was an inspiring slate to inherit, and for us, it sets the path to take the documentary slate forward.

Leena, I understand that the challenges of making House of Secrets would be manifold. What were the biggest?

Leena: Right from the word go, I knew I had to get permission to interview the cops who had investigated this case. Without that, we wouldn’t have had a complete story. I met Amulya Patnaik, the then Delhi commissioner of police, and he gave me permission to interview cops across the board. I then started meeting the relatives and friends of the family.

The challenge lay in making people speak the truth about the case. As Indians, we generally believe ki ghar ki baat ghar mein rehni chahiye. It’s a tricky thing to say, but we do pay more respect to the dead than to the living. So, once someone is dead, no one wants to speak anything bad about them... ‘Bahut achhe log thhey, sab achha tha.’

Also, most people here are not very aware of the documentary culture. A lot of those we approached said: ‘Nahin, nahin, hum acting nahin karenge.’ And I was like, ‘No acting... you just have to have a conversation with me.’ So just getting people to the space of actually talking was a challenge. Another thing is that we, as a society, avoid uncomfortable questions. And there was no point of making this documentary if we were unable to have those uncomfortable conversations to reach whatever truth that is out there. As a team, the challenge was the emotional up and down that making this gave all of us.

I didn’t force anyone to talk, especially those who were close to the family. There were some who chose not to speak, and I understand that because they had already gone through that trauma. But then one of the family members told me, ‘Thank you for doing this. Talking about what happened feels like therapy because we haven’t even had that conversation among ourselves’.

I enter a true crime documentary with the perspective of wanting to play detective, like a lot of people do. We all think that we are smarter than the detective in the story, right? I am actually happy if content makes me see the world in a different way or gives me some sort of wisdom

LEENA YADAV

During the pandemic last year, we did see a spike in the uptake for comedy. The funny thing is that comedy was the most popular genre then, but just behind that was crime. I think it just boils down to the mindset of the audience, and our responsibility is to provide a diverse set of stories, ones that are compelling and engaging. Crime can also be comedic, it doesn’t have to be dark and gory —

LEENA YADAV

Tanya, Leena just spoke about how people here are largely unaware of the documentary culture, in terms of participating in it. But how would you say the audience here is placed in terms of consuming the genre?

Tanya: Any platform, and ours particularly because we are present across 190 countries, I look at us as a cultural conduit. And therefore, it is our responsibility to widen the aperture for the audiences within the country and beyond, to be open to receiving different kinds of stories, and in different formats. What we have gleaned from our data, between mid-2020 and mid-2021, 76 per cent of our user base has watched at least one documentary title. We look at it as very encouraging signs.

It’s an elevated form of storytelling to the documentary genre that Netflix brings. It makes us curious about our culture, situation and environment, and at the heart of it is a very rich story, narrated beautifully through great creative voices. And when you have such great narratives, I strongly believe that stories become genre agnostic. And that’s how the audience is looking at it too.

How would the two of you decode the spike in audience interest in the true crime genre?

Tanya: True crime, or crime in itself, becomes a vehicle to tell various other stories. If you compare Bad Boy Billionaires, Burari, India Detectives or Wild Wild Country, the entry point to each may be crime, but they are all different stories. In India Detectives, I think cops have been humanised for the first time and Burari is one of the most sensitive telling of a case that shook the nation. True crime is just an entry into understanding the world around us better.

Leena: I think people are just drawn to crime, and that’s a truth that came before us. There is a part in every one of us that just wants to watch something disturbing and gory... that’s a human thing.

Isn’t it true that content that was dark and disturbing was being shunned by audiences last year when the pandemic first came calling, just given the unhappy circumstances that we were living in anyway?

Tanya: You are right. During the pandemic last year, we did see a spike in the uptake for comedy. The funny thing is that comedy was the most popular genre then, but just behind that was crime (laughs). I think it just boils down to the mindset of the audience, and our responsibility is to provide a diverse set of stories, ones that are compelling and engaging. Crime can also be comedic, it doesn’t have to be dark and gory. When I went into to watch The House of Secrets, I thought, ‘Oh my God, I am going to be really unsettled.’ But the experience was emotional and was handled with great sensitivity.

When you watch a documentary, do you go in expecting to be entertained or educated or both?

Tanya: I am delighted with the job I have because I first hear a story, read it, watch it and experience it as a viewer. It’s magical to sit with creators and hear their vision. You know a good idea when you hear it, and it’s a very special experience from the get go. Inherently, it’s curiosity that a piece of documentary, or for that matter any kind of content, elicits. As long as the questions of who, what, why, when, how — which are the golden rules of journalism, but also apply equally to story writing — are lurking, you are hooked.

Leena: I enter a true crime documentary with the perspective of wanting to play detective, like a lot of people do. We all think that we are smarter than the detective in the story, right? (Laughs) I am actually happy if content makes me see the world in a different way or gives me some sort of wisdom.

Any recent documentaries that you loved?

Leena: I liked Allen vs Farrow. The thing is that with this kind of content, you can’t even say it was fun! (Laughs) But yes, it was interesting. I also recently rewatched Don’t F**k With Cats, which is such a thrilling narrative.

Tanya: You should watch Britney vs Spears. It’s really, really interesting.