Joymoni became a liability after August 15, 1947. All kinds of assets were being divided between India and Pakistan, and Joymoni, the government-owned elephant, was no exception. At last it was decided that she was to go to East Pakistan and her mahout was to walk her across the border.

But, the mahout refused outright. He was scared of being imprisoned in a “foreign” country. Ten months later, two officials came from across the border to Malda, to take her away. The angry Indian District Collector threw them into prison for not paying the Rs 1,900 spent on the upkeep of a “foreign” elephant for 10 months.

Joymoni, in all likelihood, never got to cross the border.

This episode, sourced from the government archives in Bangladesh, finds place in Annwesha Sengupta’s book Desh Bhag, which is about Partition. It was one of three books around which a discussion titled “Itihase Hathe Khari” was organised at Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall not long ago. The other two books were Tista Das’s Desher Manush and Debarati Bagchi’s Desher Bhasa. While the former is a narrative about those displaced by Partition, the ensuing refugee crisis, detention camps and the deeply discriminatory citizenship laws, the latter is an attempt to examine the profound impact of languages on the socio-political orders of the subcontinent.

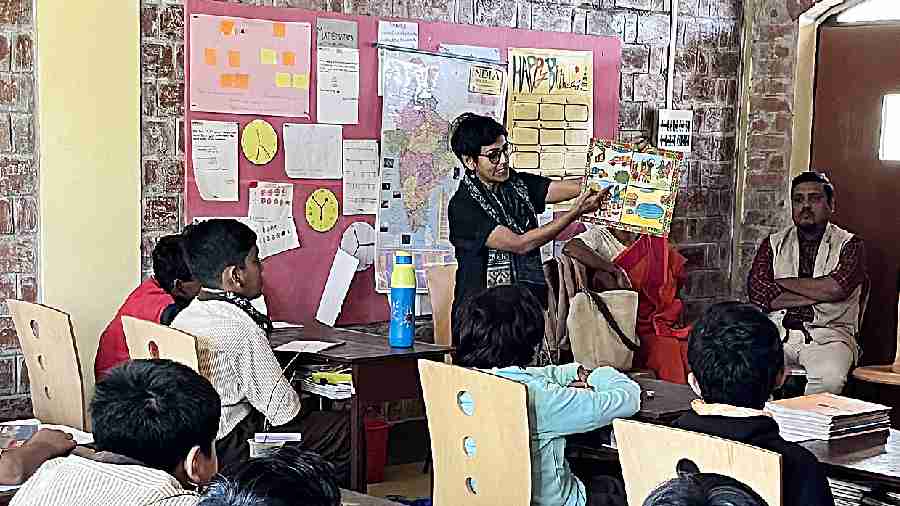

The books are the products of the ongoing project Revisiting the Craft of History Writing for Children, funded by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung South Asia foundation, housed at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata. The books published in Bengali and Assamese are aimed at teaching history with a more intimate and critical perspective, to students in the age group of 12 to 14. Their aim is to disentangle complex episodes of history, while still conveying their essence that children may read them as supplements to their school texts and learn to ask pertinent questions.

To return to Joymoni, tales such as hers almost never find their way into the straitjacketed world of academic curriculum. Das points out how children are unlikely to hear the story of Gangadhar from Bengal or Hasina Bhanu from Assam, who were forced into transit camps. Sengupta recounts the poignant tale of the farmer Nasir, standing at the border and looking longingly at the paddy fields of Assam from where he was deported to Mymensingh in 1964.

In discussion that evening at Victoria Memorial Hall were journalist Swati Bhattacharya of Anandabazar Patrika and Hia Sen who teaches sociology at Presidency University. Sen said there have been some attempts at writing about “difficult” pasts for children, as in Abanindranath Tagore’s Raj Kahini or Leela Majumdar’s fictionalised works on ghosts of refugee children. In a candid discussion, Sen drew attention to the fact that there have always been debates or disputes around questions of language and the themes considered to be “child-appropriate”. She said, “The three writers here have experimented with acquainting the children with ‘difficult histories’ by deliberately avoiding the usual didactic tone, and gently introducing them to critical perspectives with which they can look at the past and the present.”

Bhattacharya said, “Undoubtedly there is a need for such an effort, but it could also throw up a situation of equivocation because of the large number of possibilities explored”. She added that without opening up the premises for doubt, history as a subject tended to become just a preset sequence of events, to which students are to conform passively.

Bagchi recalled the example cited by a history teacher of a government school in an online workshop conducted for the school teachers of West Bengal. The teacher, who is also a member of the syllabus committee of the state, said that while Mohammed Ali Jinnah is generally portrayed as the “villain” of the Partition, many historians have come forward with not-so-incriminating theories which propose that initially he did not support the Partition at all. Eventually though it became imperative to put forward Jinnah as the villain or hero, for the creation of the distinctive national identities of India and Pakistan.

This is possibly the kind of trope in history Bhattacharyareferred to when she spoke about the tendency of the administrators of civil society to promote an undemocratic unilateral perspective of history in order to infantilise society. She invoked Gayatri Chakravarty Spivak and how she has often said that the kind of education which is essential for democracy is teaching children to ask questions to imagine situations that are not apparent.

Bagchi stated that at such a time as this when history has become a domain of violent contentions in the country, the purpose of the “Itihase Hathe Khari” series is to disseminate an enhanced understanding of critical histories of the Indian nation-state, nationalism and promote a sense of national belonging among children, parents, educators, activists and community artists.