On a meandering mushroom hunt at NorthSouth Lake in the Catskill Mountains of New York in the United States, Jessica Rosenkrantz spotted a favourite mushroom: the hexagonal-pored polypore. Rosenkrantz is partial to life-forms that are different from humans (and from mammals generally), although two of her favourite humans joined on the hike: her husband, Jesse Louis-Rosenberg, and their toddler, Xyla, who set the pace. Rosenkrantz loves fungi, lichens and coral because, she said, “they’re pretty strange, compared to us”. From the top, the hexagonal polypore looks like any boring brown mushroom (albeit sometimes with an orange glow), but flip it over and there’s a perfect array of six-sided polygons tessellating the underside of the cap.

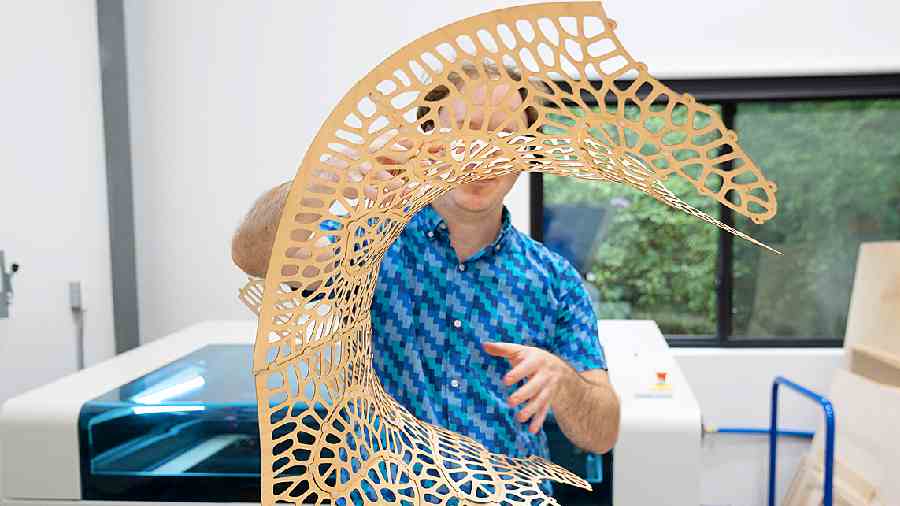

Rosenkrantz and Louis-Rosenberg are algorithmic artists who make laser-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles at their design studio, Nervous System, in Palenville, New York. Inspired by how shapes and forms emerge in nature, they write custom software to “grow” intertwining puzzle pieces. Their signature puzzle cuts have names like dendrite, amoeba, maze and wave.

Beyond the natural and algorithmic realms, the couple draw their creativity from many points around the compass: science, maths, art and fuzzy zones between. Chris Yates, an artist who makes hand-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles (and a collaborator), described their puzzle-making as “not just pushing the envelope — they’re ripping it apart and starting fresh”.

The day of the hike, Rosenkrantz and Louis-Rosenberg’s newest puzzle emerged hot from the laser cutter. This creation combined the craft of paper marbling with a tried-and-true Nervous System invention: the infinity puzzle. Having no fixed shape and no set boundary, an infinity puzzle can be assembled and reassembled in numerous ways, seemingly ad infinitum.

Nervous System debuted this conceptual design with the Infinite Galaxy Puzzle, featuring a photograph of the Milky Way on both sides. “You can only ever see half the image at once,” Louis-Rosenberg said. “And every time you do the puzzle, theoretically you see a different part of the image.” Mathematically, he explained, the design is inspired by the “mind-boggling” topology of a Klein bottle: a “non-orientable closed surface”, with no inside, outside, up or down. “It’s all continuous,” he said. The puzzle goes on and on, wrapping around top to bottom, side to side. With a trick: the puzzle “tiles with a flip”, meaning that any piece from the right side connects to the left side, but only after the piece is flipped over.

Rosenkrantz recalled that the infinity puzzle’s debut prompted some philosophising on social media: “A puzzle that never ends? What does it mean? Is it even a puzzle if it doesn’t end?” There were also questions about its masterminds’ motivations. “What evil, mad, maniacal people would ever create such a dastardly puzzle that you can never finish?” she said.

A ‘convoluted’ process

Rosenkrantz and Louis-Rosenberg trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US. She earned two degrees, biology and architecture; he dropped out after three years of mathematics. They call their creative process “convoluted” — they get captivated with the seed of an idea, and then hunt around for its telos.

A project that came to fruition this year, the Puzzle Cell Lamp, built upon research about how to cut curved surfaces so the puzzle pieces can be efficiently flattened, making fabrication and shipping easier.

“When you try to build a curved object out of flat material, there’s always a fundamental tension,” said Keenan Crane, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, US. “The more cuts you make, the easier it is to flatten but the harder it is to assemble.” Crane and Nicholas Sharp, a senior research scientist at NVIDIA, a 3D technology company, crafted an algorithm that tries to find an optimal solution to this problem. Using this algorithm, Rosenkrantz and Louis-Rosenberg delineated 18 flat puzzle pieces that are shipped in what looks like a large pizza box. “By snapping the shapes together,” the Nervous System blog explains, “you will create a spherical lamp shade.”

Recreating Earth

The Puzzle Cell Lamp takes its name from the interlocking puzzle cells found in many leaves, but this lamp is not a puzzle proper — it comes with instructions. Then again, one could ignore the instructions and organically devise an assembly strategy.

Nervous System’s most challenging infinity puzzle is a map of Earth. It has the topology of a sphere, but it’s a sphere unfolded flat by an icosahedral map projection, preserving geographic area (in contrast to some map projections that distort area) and giving the planet’s every inch equal billing.

“I’ve gotten some complaints from serious puzzlers about how hard it is,” Rosenkrantz said. The puzzle pieces have more complex behaviour; rather than tiling with a flip, they rotate 60 degrees and “zip the seams of the map,” she explained. Rosenkrantz finds the infinity factor particularly meaningful in this context. “You can create your own map of Earth,” she said, “centering it on what you’re interested in — making all the oceans continuous, or making South Africa the centre, or whatever it is that you want to see in a privileged position.” In other words, she advised on the blog, “Start anywhere and see where your journey takes you.”

NYTNS