A hot May afternoon in the early 1980s. Mr Chakrabarti had only just brought home his wife and the new-born baby, and he was in high spirits. But he was restless. He was waiting for someone; pacing up and down the long corridor of his bungalow in the small town of Jharia in Bihar (now in Jharkhand). At long last the large black iron gates swung open and a man drove in on a shiny grey-and-black Lambretta scooter. Mr Chakrabarti gasped at the sight.

It was a second-hand vehicle but there was nothing second-hand about what Mr Chakrabarti felt. He had spent weeks saving every paisa from the time he learnt that one of his colleagues had a relation in Delhi who wanted to sell a fairly new Lambretta. They found the scooter too heavy to manoeuvre and actually wanted to give it away to Mr Chakrabarti’s colleague, but he was not willing to drive a scooter.

Mr Chakrabarti had no such hesitation. You see, he knew a lot about the Lambretta from his assiduous readings. He knew that it was made in Milan in Italy, that it was named after the Lambro river that was adjacent to the factory site. He also knew that Lambretta was the name of a water fairy associated with that particular river. He was well aware of the advanced mechanics of the Lambretta and was delighted at the prospect of owning such an exotic steed. He decided to give it a shot. Three thousand five hundred and one rupees plus the freight charge was what he had to pay. That was quite a sum those days when a seer of mutton cost one rupee fifty paise.

The Lambretta had arrived from Delhi after two-and-a-half days on the Delhi-Kalka Mail. Mr Chakrabarti’s family was now complete — him and the missus, a boy, a baby girl and now the Lambretta. He was so excited that no sooner than the courier had left, he took the scooter out for a spin.

Mr Chakrabarti was a young manager at the Simla Bahal Colliery. Thus far, he bicycled to office and back, a good four kilometres distance one way. There was no public transport in the colliery and the adjoining areas. There were no buses, very few rickshaws plied and a handful of “trekkers” or jeeps could be spotted sometimes at the city centre.

On Sundays, after a breakfast of luchi-torkari, Mr Chakrabarti would walk down the narrow pathway that led to the main road to reach the lone local market, Jharia bazaar, which was at least five kilometres away. So, for good reason the Lambretta was much cherished by the Chakrabartis.

Mr Chakrabarti would make sure that the scooter was always squeaky clean. He also ensured that it got enough rest — so much so that in the initial days he would often walk to the office not wanting to bother the cucciolo. At home and to himself he would reason that he did not want to show off that he had finally managed to buy a private vehicle, that too only after eight years of service with the Bharat Coking Coal Limited. Years later, Mrs Chakrabarti would say in gentle tones with a soft faraway gaze in her eyes that most likely those days her husband was not quite at ease commandeering the heavy vehicle and feared that he would fall and hurt the dear purchase.

Jharia was nothing like Milan. It was not like Delhi either. The Simla Bahal Colliery area was very quiet. The bungalow closest to the Chakrabartis’ home was a good half-kilometre away. The “labour quarters” were one-and-a-half kilometres away from the officers’ bungalow cluster. For the longest time, the Lambretta’s sole playmate was Mr Chakrabarti’s five-year-old boy. He’d try to move the handles and make whooshing sounds with his mouth as if embarking on some terrific adventure scooter-back and at top speed.

Gradually, the Lambretta started getting used to colliery life. Mr Chakrabarti would make several trips from home to colliery in a single day. He would go out in a fresh shirt and shorts. The Lambretta would wait for him in the shed outside his office from where it could see the two giant pit wheels going round and round throughout the day. It got acquainted with the ghrrr ghrrr of the wheel working the lift, lowering people into the pit of the colliery and hauling up machinery and men.

The miners wheeled barrows loaded with coal, hoist them onto single gauge tracks from where they rolled down, reached an incline and toppled over — coal, barrow and all. The payloaders parked below would lift the coal and drop them into the waiting good trains on the adjacent railway track. At noon, when Mr Chakrabarti emerged out of the pit, his shirt would be drenched in sweat and his shorts and legs black from the coal dust. The Lambretta could feel his fatigue when he lowered himself onto its seat as he headed back home for a quick bath and refuel.

The Lambretta had heard whispers in the mines about how Mr Chakrabarti preferred to supervise the work of miners from inside the pit, instead of giving directives based on second-hand reports.

Whenever there was any accident, he and the Lambretta would head straight for ground zero. As he sat through the gheraos that were a regular feature of his job — collieries those days were beset with trade union issues — the Lambretta waited long and anxious hours. Their journeying continued.

The Lambretta witnessed Mr Chakrabarti deal with the coal mafia so omnipresent in the colliery. Once, at midnight, a man with a dagger hovered around the Chakrabartis’ bungalow. The Lambretta slunk out of the house through the backdoor with Mr Chakrabarti on its back. Only after they had reached a safe distance, did it stutter into a start, and thereafter flew to the local police station to seek help for the family still stuck in the house.

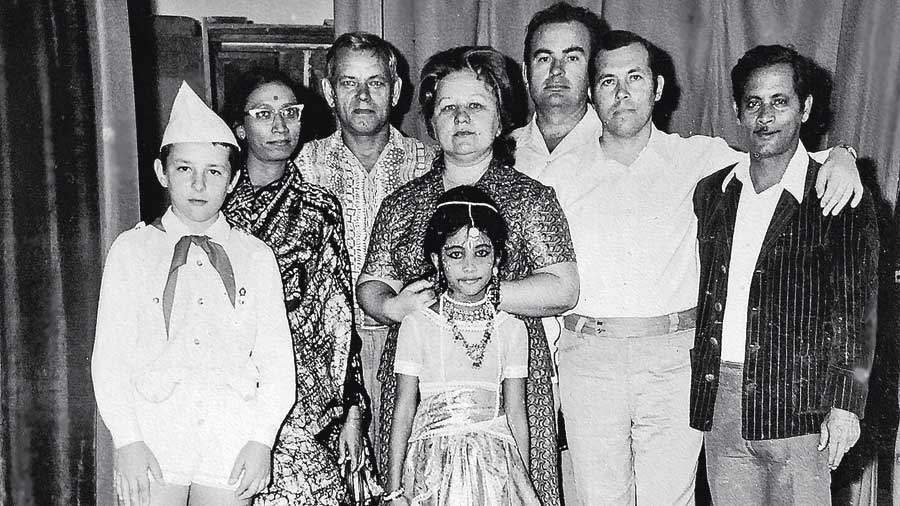

The Lambretta loved being a part of the Chakrabarti family. Mr Chakrabarti would take the whole family on rides to the local market or to some social function when there was one. The little boy would quickly wriggle into the space between the driver’s seat and the handles. Mrs Chakrabarti would ride pillion, the infant clasped tight to her breast. The Lambretta was keenly aware of its responsibility to steer them safely without a bump or jerk. Mr Chakrabarti was careful but the Lambretta was doubly careful.

On one such occasion when Mr Chakrabarti and his family were on their way back from a social visit, the Lambretta spotted a group of men in the middle of the road. The men were bare bodied, impressively moustachioed, gamcha tied around the head, torch in one hand and a long, thick staff in the other. The Lambretta heard Mr Chakrabarti whisper “dacoits”. His tone something between a warning and an exclamation.

As the scooter came closer to the men, the leader of the pack came forward and signalled them to stop. Mr Chakrabarti slowed down though the Lambretta wished otherwise. It said to itself, “If only Mr Chakrabarti would shift to fourth gear, I could scamper off the main road and into the bushes and hurry them to safety.”

It was as if Mr Chakrabarti had read the Lambretta’s mind. No sooner than the dacoit lowered his hand, Mr Chakrabarti shifted gear and raced. The Lambretta had strong and sturdy tyres and with added willpower it negotiated through an extremely difficult terrain, stopping only when it had reached the portico of the scarlet bungalow.

The next day Mr Chakrabarti patted the Lambretta on its back fondly. He also took it to the local technician, who gave the scooter a thorough check-up and a fit certificate.

The Lambretta stayed on with the Chakrabartis for a decade. It saw the infant grow up and go to school. Mr Chakrabarti shifted from Simla Bahal to Koyla Bhawan and then to Kirkend Colliery — both in the Dhanbad district. The Lambretta routinely ferried the little girl to her Kathak lessons and the boy to his tabla classes.

And all was well till one day, when Mr Chakrabarti was returning home from office. The Lambretta had a fleeting spasm and stopped. Nothing could revive it. Mr Chakrabarti took it to the technician. In all these years, the scooter had developed the occasional problem with the starter, the gear, the brake shoe, the accelerator wire, the carburetor, but this time there was some problem with the engine. A part had to be changed Mr Chakrabarti was told and he left no stone unturned to try and procure it.

But it turned out that the parts were not being manufactured any more. The technician tried to whip up a jugaad, some local make of the missing part, but the Lambretta was never quite its old self again.

After much thought, Mr Chakrabarti steeled himself and exchanged it for a red LML Vespa and, eventually, a four-wheeler. After his retirement several years later, Mr Chakrabarti shifted to a gearless scooty, but till the last years of his life he kept thinking about his Lambretta. This was years after his little boy had sped off to another world. Even after he was joined there by Mrs Chakrabarti.

The year Mr Chakrabarti’s baby girl got married, as he examined the son-in-law’s two-wheeler, he said unimpressed, “There can never be any gaari like my 1030, my Lambretta.”