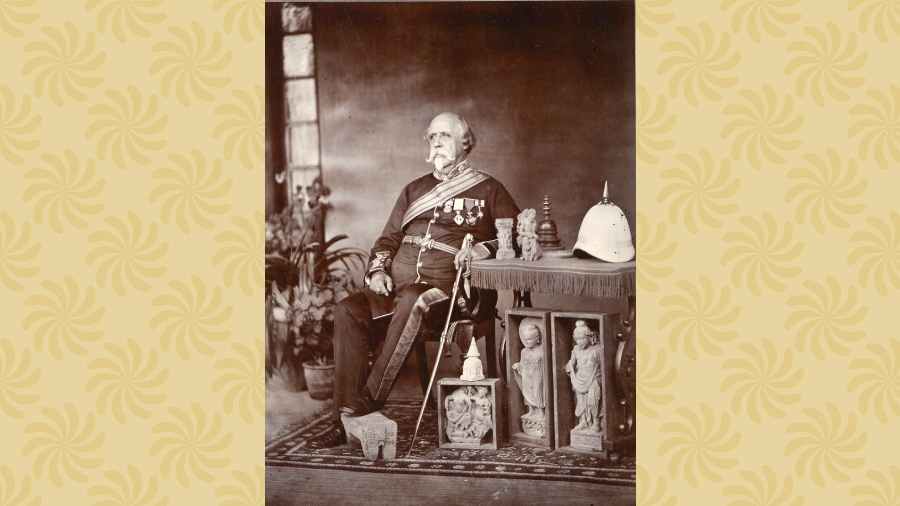

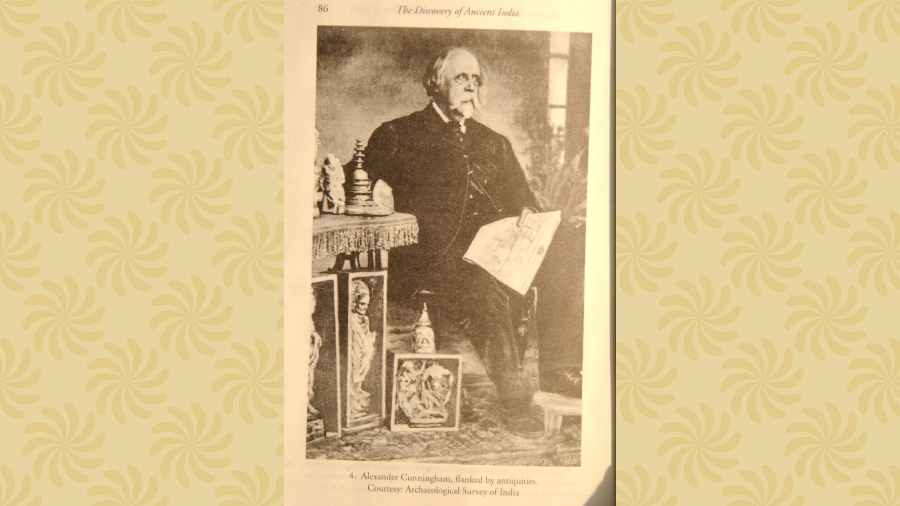

Alexander Cunningham was the first director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and J.D.M. Beglar, his assistant. The two, along with A.C.L. Carlleyle, were the first office-bearers of the ASI. That the Briton and the Armenian shared an enduring relationship was common enough knowledge. Then, in 2005, Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH) acquired a bunch of letters, mostly from Cunningham to Beglar.

“The letters (written between 1871 and 1886) revealed unknown facets of Cunningham’s personal and professional life and offered fascinating glimpses of the world he lived in. They are an enormously rich new source for the history of Indian archaeology,” says Upinder Singh. An ancient Indian history scholar, Singh has for long researched Cunningham and written about him and his work. When she came to know about the letters, she wrote to the VMH requesting permission to edit and publish them.

That was in 2006. The World of India’s First Archaeologist, Letters from Alexander Cunningham to JDM Beglar was co-published by VMH and the Oxford University Press in October 2021. Cunningham usually spent the winters in the field and the letters were written while he was on the move or from camps on-site. “Several letters were written from Fir Hill, Shimla. Some were written from Calcutta… Others were written in Roorkee where Cunningham’s son Allan taught. The last few were written after he returned home to Cranley Mansion on Gloucester Road in South Kensington,” writes Singh in the Introduction.

The first letter, written on January 28, 1871, was a formal invitation to Beglar, who was then a PWD engineer, to join his team. Cunningham had heard of Beglar’s interest in photography and he had asked for some of his photographs. “The letter had an urgency to it. He wanted Beglar to decide immediately if he wanted the job,” adds Singh. The second letter is dated 1874. By that time, the two men were better acquainted. Cunningham’s letters began with “My dear Beglar” instead of “Dear Sir”. The frequency varied and there were long spells of silence as well.

Joseph David Beglar Pictures, courtesy Leiden University Library

In the 1870s and 1880s, the ASI was a three-man team with a couple of support staff. “This single fact makes their achievements all the more remarkable,” says Singh. The two men planned their itineraries such that they could meet during fieldwork. Beglar sent drafts of his reports to Cunningham, who at times praised them and at times ruthlessly criticised them. But there was also personal warmth and humour.

The letters describe archaeological discoveries — several of major historical importance — as they were made in real time. In 1875, Cunningham reports : “ Carllyleh as found Kapilavastu at Bhuila Tal, a place described by Buchanan.” That autumn he writes: “I have got proof that Pataliputra was on the Son.” From Mathura in 1882: “I found only one sculpture of any value. This is however a really valuable one — a group of Herakles killing the Nemean Lion!”

The letters transport the readers into the hustle and bustle of archaeological expeditions. There are repeated references to the weather. Cunningham complains of the heat thus: “I am now melting away very fast.” There are references to Beglar’s fever and headaches, and Cunningham regularly makes enquiries about his health.

Cunningham, one gathers from the exchange, kept up the pressure on his assistants. He feared that if the Archaeological Survey reports were not published on time, he would face punitive action from the government.

Though surface exploration was what the ASI focused on, Cunningham was eager to excavate at Mathura, Garhwa, Bhitari and Kosam. He was keen on opening stupas for relics. Excavations were conducted at Bodh Gaya and Vaishali. Ashokan inscriptions were an abiding passion for him. Remains of the Bharhut Stupa were discovered by Cunningham in November 1873. He was also largely responsible for removing the Bharhut sculptures to the Indian Museum in Calcutta, which has a dedicated gallery to it. After Bharhut, it was the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya that both Cunningham and Beglar worked on.

Both men were widowed relatively early in life. They wrote to each other seeking comfort. Beglar moved between Chakdah and Chinsurah. Cunningham was joined by his sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren in Shimla.

Cunningham’s handwriting becomes smaller and untidy from the 1880s. In September 1884, he informs Beglar he will resign. He is ready to leave but the ship carrying his possessions sinks. He loses his wife’s portrait, papers, photographs and books. Beglar replaces as many books and photographs as he could. Cunningham writes: “I am afraid you will never be a rich man.” In February 1886, he sets sail for England.

The last letter in the collection reads thus: “I shall always be very glad to hear from you, and of your work. Believe in me to be always your sincere friend. Alex Cunningham.”