When Russia announced that it had named the coronavirus vaccine developed by Moscow’s Gamaleya Research Institute, Sputnik V, it brought forth an avalanche of memories. Growing up in the Bokaro Steel City, a part of Bihar until Jharkhand came into being in 2000, my association with Russia ran deep.

The Bokaro plant had been built in collaboration with the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or the Soviet Union, in the 1960s. But first the Sputnik story.

As children the very mention of Sputnik would set us giggling, and all because one day one of the mothers had threatened us with it. It was past dusk and we were still out in the playground and not home poring over school texts as was expected of us. One kakima said to the collective, “It will serve you right when in the dark Sputnik falls on your heads.” Much later we learnt that the USSR had sent up Sputnik 24 to Mars in 1962, but there was a snag and the spacecraft eventually fell back on Earth, in smithereens.

In 1961, my father had moved to Marafari, a village in the Chhotanagpur jungles in Dhanbad district to join the Bokaro Steel Project. Those days, the jungles were being cleared for the steel plant and the city, and I am told Baba and his colleagues lived in tents for the next couple of years.

As the project developed, the Russians were roped in. The township also grew beyond the design table. A portion of Sector IV was walled off for the Russians and came to be known as the Russian Colony.

No Indian could enter the Russian Colony without a special pass. Likewise, no Russian could step out or invite inside any Indian without permission from the concerned authorities.

Besides residential quarters, the Russian Colony had a club, a primary school, a shopping centre as well as a small playground-cum-park.

The Russian engineers and interpreters, who came on assignment to Bokaro — 40 to 50 of them, some with family and some by themselves — lived there for a maximum of three years at a stretch.

My father was the administrative and public relations officer in charge of the Russians. This meant my mother and I had access to the Russian Colony, including its market — Tejoomals Jewellers of New Market had a counter there — and the tailor, Damaiyya, a master craftsman who didn’t need my measurements as he had a daughter my age.

The year (1984) Rakesh Sharma flew into space aboard the Soyuz T-11, I got to catch the live telecast on the giant colour television installed in the colony club. The rest of Bokaro did not have television services till later that year.

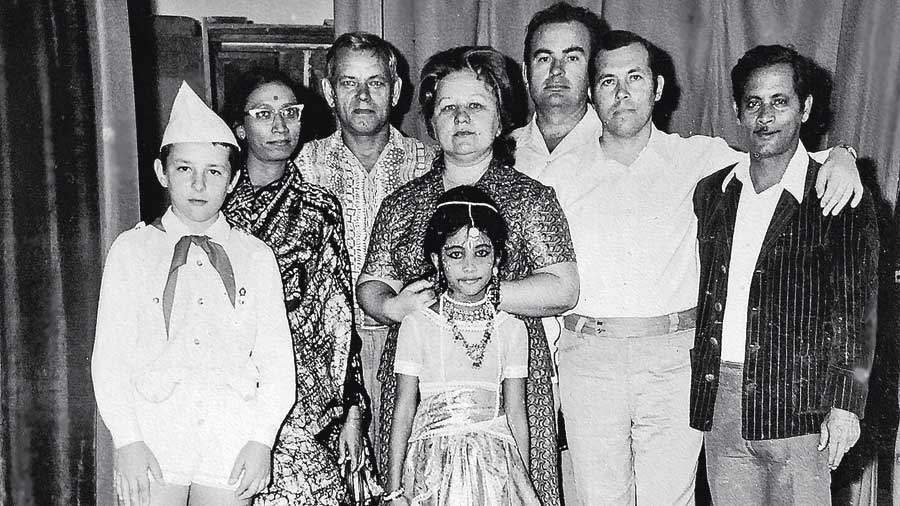

And it is at this club, many years earlier, that Mrs Kasalova declared that I was to be her daughter-in-law. I was in Class II, and the groom-to-be, whose name I cannot recall anymore, was in middle school back in the USSR. The announcement came on the heels of my Bharatnatyam recital on the occasion of Indo-Soviet Friendship Day — the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Co-operation had been signed on August 9, 1971. Master Kasalov was visiting his parents and had participated in a group dance earlier that evening. After my performance, both families posed for a group photograph.

Long after the family left Bokaro, Mrs Kasalova kept in touch through whoever was in town. And when the son took up English in college, she was elated that the language barrier between him and me would be transcended and no third person would have to play interpreter.

The only Russian I remember today are snatches of phrases and words — Kak vas zavoot; spasiba.

My parents would host dinners for the Russian families. Chefs from Bokaro Hotel — the company’s accommodation for its visitors — would be summoned for these dos. They whipped up Russian and select Indian dishes. I had to spend those evenings cooped in my room with my mother coming in frequently to check if I needed something. A different aroma would waft through the house that day, drinks flowed freely, glasses clinked...

There would be at least two to three Russian families at these get-togethers as individual social interactions were not allowed by the Soviet Union. A Russian interpreter was always present.

My mother tells me how on one rare occasion the families had been invited children et al. It seems the little ones had no idea of life and town outside the colony walls and were so overwhelmed with the experience that they had wept.

That day, while the adults partied in the big drawing room, four of us were relegated to the adjacent room. According to my mother, when she came to check on us, she found us playing and chattering away merrily although they didn’t know my tongue and I knew nothing of theirs. “It struck me that the problems and barriers develop as we grow older,” she tells me now so many years later, and adds, “the innocence and ease of communication of children are lost.”

The visitors would always come bearing gifts — the doll-within-doll matryoshkas, a blue-eyed baby in woollen overalls with two pompoms tied at the neck, smaller wooden dolls and miniature Russian folk dancers. They went home with curios and Lipton’s Green Label tea packs. In fact, the Russians so loved this tea that they would carry home as many packs as they could when returning to the USSR.

Not everyone was a tea fan though. Mr Likutin the interpreter, for instance, loved his tipple a bit too much. A jolly and affable man, he had struck a friendship with my father. One morning, Mr Likutin stepped into a watering hole in the adjacent and olden town of Chas and came out so sloshed that he slumped onto the road before he could reach his car. The next day my father had to see off his dear friend at the city aerodrome. Mr Likutin had been “deported to Siberia” as punishment. The Soviet state wouldn’t tolerate the slightest misdemeanour from its citizens outside the Russian Colony.

The Russians were not allowed out, but all their provisions came from outside. A blue pick-up van would leave for Ranchi before sunrise every Wednesday and Saturday. It would return by sunset laden with provisions — beef and vegetables from Doranda, pork and sausages from the Bacon Factory in Kanke.

Many a time I would tag along either to visit Thama, my grandmother, or my aunt and her family. Later, when the plant was ready and the number of Russians had dwindled, only an Ambassador car would suffice for the procurements.

The Russians had their clothes and accessories sourced from Delhi. And that’s how I got my first pair of jeans, way before the fad reached Bokaro. When a Russian family left, they’d give away some of their belongings. That is how I got my first cycle, a blue beauty with over two-inch thick tyres and support wheels, and a few years on, a regular sky-blue lady’s cycle with curved handle-bars. It was so “cool” that all I had to do was back-pedal and the cycle would come to a halt. My first wristwatch, a square thing with a silver matt-finish dial and a black strap, when I was in Class VII, was a Russian hand-me-down. And so was my second — a golden, longish timepiece with narrow, black bands — which saw me through middle school to university. The list was endless — a two-foot high brown bear that would moan when turned face down, a guitar...

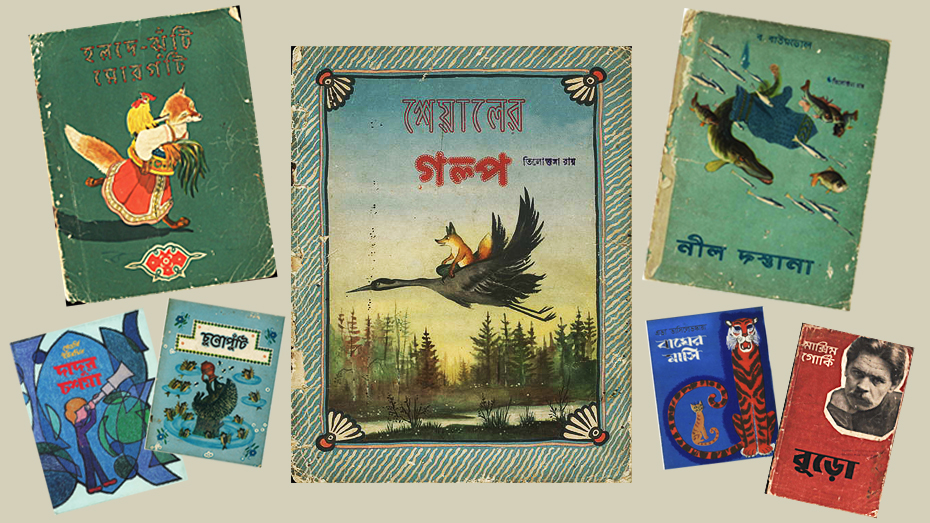

The magazines, Sputnik and Soviet Land, arrived by book post every month and the English translations of Soviet literature — Tolstoy, Turgnev, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, Gogol — by Progress Publishers were available in the Russian colony bookshop. And yes, they also sold beautifully illustrated and colourful children’s books.

In 1987 my father opted for a transfer to Ranchi. The USSR broke up in 1991 and soon after, the last of the Russians left. The walls of the Russian Colony too came down.

Sometime between our leaving and the Russians’ final goodbye, I visited Bokaro. I met an old neighbour, who was also four years my junior from school, and her classmates remembered my Damaiyya-tailored dresses. I met my classmates who remembered me for the Russian bicycle with fancy brakes.

That trip I learnt one more thing — Mrs Kasalova’s son had got himself a girlfriend and gone and broken his mother’s heart.