This year, the Calcutta Book Fair had Russia as its theme country. The outer walls of the boxy pavilion adorned with illustrations of the Kremlin Grand Palace and the Bolshoi Theatre against a spliced pastel blue and green horizon mimicked beautifully illustrated Russian children’s books such as those several generations of Indians have grown up with. Inside, there was a table laden with books on sale — Hindi, Bengali and English versions of Russian books — and another wall full of those in Russian, one of which was a translation of Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate. The curved back wall of the pavilion had a single row of foot-high illustrations from Afanasy Nikitin’s A Journey Beyond the Three Seas, the story of a Russian merchant from Tver who travelled to India in the 15th century. When Three Seas was translated into Bengali by Purabi Roy sometime in the mid-1990s, Teen Samudra Parer Kotha became one of the most popular Russian books in translation. To date, generations of Bengalis know the stories of Ma (Maxim Gorky’s Mother), Ispat (Nikolai Ostrovsky’s How The Steel Was Tempered), Juddho aar Shanti (Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace), Mishka Bhaluk (Misha the Little Bear), Anari (Dunno’s Adventures) and Altajoba (The Scarlet Flower), though they may have well forgotten the Russian connection.

Jessica Bachman of the University of Washington’s department of history has studied the Indo-Soviet literary exchange closely. She has explained in more than one interview how in the years after Joseph Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union made a concerted effort to distribute books to India and many other postcolonial nations, offering them at low or no cost. She said, “The Soviets translated texts from all the different Soviet languages into 13 Indian languages as well as English… They had the largest translation programme in the world.”

Post Independence, paper was in short supply in India and to own a book was to hold a privileged status. There was a great demand for books on maths, the sciences and education as developing these fields was top priority. The Soviets were more than happy to supply these books at minimal cost. Books on politics, economics and literary classics — translations of Gorky, Tolstoy, Pushkin, Chekov, Dostoevsky — followed. Beautifully illustrated children’s books were made possible by the offset printing press, which India didn’t have at that point. It was for the Soviets part of their soft power expansion.

“They were always beautifully illustrated,” says Aveek Majumder, who grew up in the 1970s surrounded by English and Bengali translations of Russian literature. He adds, “The average middle-class family could not afford English children’s books. But the English translations brought out by Russian publishers were absurdly cheap, as were the Bengali ones.” Majumder, who teaches comparative literature at Jadavpur University, recalls Raduga Publishers; some of the other publishers were Progress and Mir that published scientific and technical titles, including children’s science books. Progress published books such as Duniya Knapano Dosh Din (10 days That Rocked The World by John Reed), and Khnora Raajkumar (The Lame Prince by Alexie Tolstoy).

Of course, the Soviet books were reaching other parts of India as well. Rigvedita Parakh, now a pathologist working in Washington, was a little girl in a small town in Maharashtra in the 1980s. She says, “Chuk And Guk was my favourite. It resonated with me, I carried it everywhere with me until it fell to pieces.” Chuk And Guk was the story of two brothers who undertook a trans-Siberian train journey to find their father. Parakh remembers the short sentences and one sentence in particular got etched in her brain. “It read, ‘Their father worked very hard but he still couldn’t complete his work’. That reminded me of my own father, always busy,” says Parakh who has managed to procure a soft copy for her two young daughters.

Soviet books were not read by children alone. “Indian freedom fighters carried with them Gorky’s Mother,” says Gautam Ghose, programme officer of Gorky Sadan, the Russian Cultural Centre in Calcutta. He adds, “I will say it was a two-way street — a love for Communism which influenced the love for Russian literature and vice-versa.”

But oftentimes it was not about the USSR at all. “I bought the entire (Alexander) Pushkin collection for only Rs 2 from the People’s Publishing House in New Delhi,” says Girish Munjal who teaches Russian at Delhi University. It sparked in him a curiosity about the country and the language, so much so that he started learning Russian and, eventually, did a master’s in it after graduating in chemistry. Currently, Munjal is translating Zuleika Opens her Eyes by Guzel Yakhina into Hindi.

Zuleika is a popular contemporary Russian novel that revolves around a strong woman character, much like Gorky’s Mother. “I think it will resonate with Bengalis,” says literary critic Galina Yuzefovich, who was in town for the book fair. She says, “It never fails to amaze me that my Indian contemporaries grew up reading the same books that I did.” Books like Aelita, Volokolamsk Highway, Plutonia, The Storm, The Government Inspector, Yevgeny Onegin, Vladimir Illich Lenin and The Cherry Orchard. And there was all that wondrous children’s literature — Ukranian Fairy Tales, Tales from Russia, Kashtanka, Fennist the Falcon, Sister Alyunishka and Brother Ivanuska, Vassilisa the Beautiful...

The Mitten, a Ukranian fairy tale about a mitten that provided shelter to anyone who sought it in a snowstorm, was translated into Bengali by Nani Bhowmick. Dadur Dostana, as it was titled, was published in 1955. “It was one of my first books,” says Abhigyan Gupta, a media professional in his late 30s. He recalls the cover of the English version — black and in the shape of a mitten. The Bengali version, it seems, had a cream cover with the illustration of a mitten and a border of flowers. Each book was elaborately illustrated, with curlicue borders and multi-coloured pictures on saturated backgrounds of green or blue or yellow. Some publishers went to the other extreme with stark black and white sketches and lots of white space. The language of the books, whether they were in Bengali or English, was very familiar but the reality the stories were grounded in was totally foreign — snowfall and frozen rivers, pike fishing and herding geese, tunics (rubakhas) and sarafan (pinafore dress), mittens and fur caps, evergreens and grizzlies, Tootsie the Heir and Prospero the Gunsmith. The essence of the stories were contained in translation and the detailed illustrations ushered the readers into a little-known world.

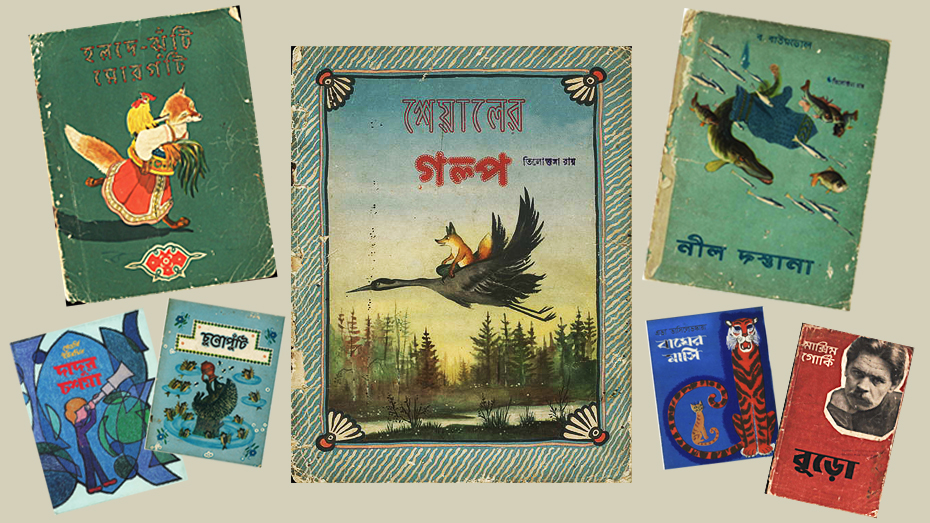

In the 1970s, 80s, right through to the 1990s, the book stalls put up by the Left parties on occasions such as the Durga Puja and various melas always stocked Russian children’s books in translation. Naam Chhilo Tar Evan, Bahadur Pnipre, Morogchhana, Pith Danaber Puri, Dhaala Knukur, Shamla Kaan. And the everyman or boy was almost always an Ivan. If he wasn’t Tsarevich Ivan or Prince Ivan, it was Ivan the fool, incapable of doing any work and yet emerging victorious in the end. There was Baba Yaga, the green-hued witch who lived in a revolving hut that stood on a chicken leg. There was the wily fox and the brave goose, Eushka the cat, and the princess with a foot-high headdress, richly embroidered in gold print. Some characters were mischievous, some saintly, some quarrelsome, some jealous and many cowardly. The books moulded the imagination of children, worked on the value systems, and perhaps taught them to appreciate art.

The Russian pavilion at the book fair had framed covers of many such children’s books on display. Very many visitors enquired if they were for sale. Unfortunately, with the publishers having shut shop, no one knows who holds the copyright of these books anymore, which is also why legitimate reprints are impossible. Some of these books, however, are now available online. In 2012, Somnath Dasgupta, Prosenjit Bandyopadhyay, Nirjon Sen, Souradip Sinha and Farid Akhtar Porag launched a website (sovietbooksinbengali.blogspot.com) where the Soviet-published children’s books are scanned and uploaded. In the last eight years, Dasgupta and his friends — all of whom are in different professions — have managed to upload around 400 such books.

Fond as he is of Russian literature, Dasgupta regards these works as “propaganda literature”. Bachman, however, believes that the Soviet Union’s efforts to translate and distribute its books went beyond politics and reflected its genuine interest in protecting and supporting the diversity of national linguistic identities in the world. The truth possibly lies somewhere in between.

To facilitate a global presence and have people read these books in their own languages, the Soviets needed translators. Most of the translators were drawn from the students at the Indo-Soviet Cultural Society set up in 1951. “That was the only place then in India where you could learn Russian,” says translator and alumnus Arun Som. The books were translated and printed in the USSR and then shipped to India. The price usually covered only transportation costs. “The publishing houses did not choose which books to translate; it was decided by higher authorities. Most of the chosen books were political and occupying second spot were literary works; 80 per cent of these was children’s literature,” says Som, who lived in Moscow and worked for Progress and later Raduga Publishers.

According to Som, 82, the translators earned a lot of money. He himself had taken up the study of Russian in his youth because he wanted to translate books by authors such as Pushkin into Bengali. “The Bengali translations of Pushkin’s works available then were translated from the English version, not the original,” he explains. According to him, after the creation of Bangladesh, the volume of Russian to Bengali translations increased. “Bengali was one of the biggest departments in Progress,” he says.

“Till 1991, the Soviet government had a special programme for translation of Soviet literature into various languages, including English, Hindi and Bengali. The books were highly subsidised, making them extremely affordable,” says Hari Vasudevan, who teaches history at Calcutta University and is an expert on Indo-Russian relations.

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union nearly 30 years ago, the money that subsidised these books dried up. The publishers shut shop. But it seems Russia has started subsidising translations again. Natalya Volkova’s young adult fiction, Multicoloured Snow, was recently published in Bengali by Dey’s Publishing — Rong-beronger Borof, which also brought out Anna Goranchova’s children’s book Enya r Elyar Kotha (The Story Of Enya And Elya).

Goranchova, who is a psychologist, tells The Telegraph, “The best way to teach children is to tell them stories.” She has two of her own, Ivan and Alyunushka. Names anyone who has read Russian tales will be quite familiar with.