The Raja Rammohun Roy Memorial Hall in Radhanagar in Bengal’s Hooghly district is clearly visible from the main road. Radhanagar is the birthplace of Rammohun Roy, polyglot, social reformer, educationist, founder of the Brahmo Samaj, the original Renaissance Man of Bengal. Off the main road is a lane with two large walled compounds on either side. Compound 1 is where Roy’s father Ramkanta had built a house. Today, standing in its place is the Radhanagar Rammohun Memorial Hall. Compound 2 houses the Rammohun Library and a replica of Roy’s tomb in Bristol; he died in the United Kingdom in 1833.

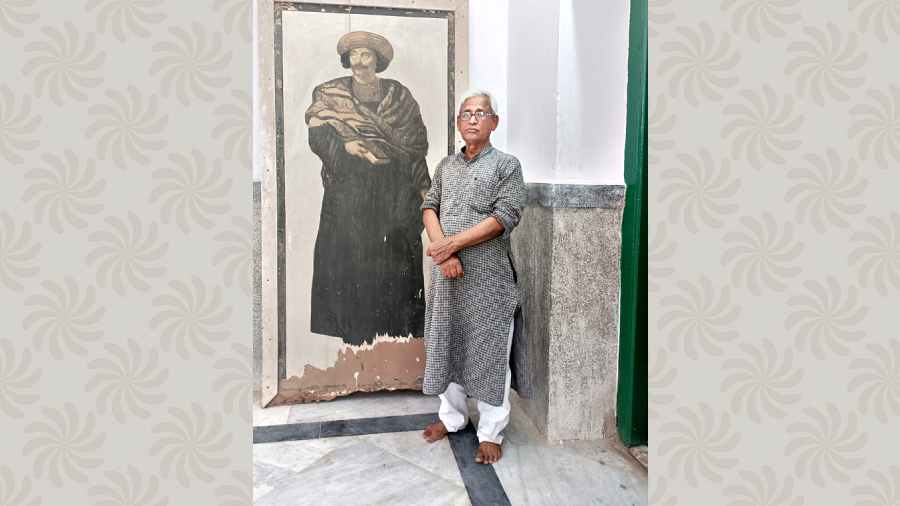

Nityabrata Mukherjee lives in Radhanagar and is a retired state government employee. His ancestors are from the same family as Roy’s. The 73-year-old keeps talking about how his family has done its best to preserve the memories of their illustrious forefather.

May 22 marked the 250th birth anniversary of Roy. I visited the place a fortnight before that. “In Calcutta there is a statue of him in one corner of the Maidan. It was inaugurated by Gyani Zail Singh in 1983, when he was President of India,” says Ananda Kundu of Radhanagar Palli Samiti, a 99-year-old organisation that has been working towards the preservation of the memories of Roy. Kundu continues, “Every other statue in Calcutta has an electric light glowing at the base, but not this one. We requested the mayor, Firad Hakim, to have it lit up before the anniversary.”

It is not too different a scenario in Radhanagar, 70 kilometres away from Calcutta. According to Kundu, Indira Gandhi was the last dignitary to visit the place. Two postal stamps were released on the 100th and 150th birth anniversaries of Rammohun and that was that.

Mukherjee and I walk into Compound 1. He points to a structure at the entrance. He says, “That was the room where Tarini Devi gave birth to Roy in 1772.” The memorial hall was constructed by the first members of the Palli Samiti — educationist Jatindranath Basu was the secretary, Nobel laureate Rabindranth Tagore was the president and poet Satyendranath Dutta was the treasurer. The foundation stone was laid by Haimanti Devi of Jorasanko Thakurbari and Tagore himself conceptualised the house — though the sketch by him was lost long ago. There is a temple to the left of the building; the arches are like those you see in mosques. There is a pentagonal altar on the rear side of the building. “It was supposed to represent Christianity but was not completed,” explains Mukherjee. Work on the building started in 1916 from donations by the people of Calcutta and Radhanagar. The highest donation was as much as one paisa.

Nityabrata Mukherjee with his illustrious ancestor’s portrait. Moumita Chaudhuri

Though completed in 1929, the memorial hall remained a blind spot. And then in 1977, Jyoti Basu, who was then the chief minister of West Bengal, decided to make a museum of it. He donated some sculptures. At some point in the 1990s, a clay bust of Roy was commissioned; now it stands purposeless in the middle of a passageway. In one corner of the hall there is a larger-thanlife oil painting of Roy by Sisir Pal. Someone, or more, has disfigured it. “Some child perhaps,” says Mukherjee. Possible, except that the portrait is taller than him.

No one ever goes to the library in Compound 2 that was opened in 2001 by the Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation, Calcutta, not even researchers. “They could not even pay the librarian the Rs 500-a-month honorarium,” says Mukherjee.

The Raja Rammohun Roy Mahavidyalaya in the neighbourhood was founded in 1964. It offers undergraduate courses in arts, science and commerce. It is closed for the summer vacations, but the cook at the college canteen, Pradip Ghosh, tells me that I must visit the Aambagan or mango grove. “Roy had planted a mango tree in the northeast corner,” says Mukherjee. Ghosh adds, “But it was Roy’s father who planted the trees. The grove belonged to him.”

What is today famed as the mango grove used to be the site of a crematorium till the mid-19th century. There is a pond close by; this is where the widows bathed and were “cleansed” before being led up to join the dead husband on the burning pyre. “If they resisted, they were beaten up and their limbs broken so they could not escape,” says Mukherjee, his voice nearly drowned by the cheerful chatter of the tourists around. He points to a marble altar inside an enclosure. It bears the following inscription in Bengali script — Satidaha Bedi.

Mukherjee continues, “This is where Alak Manjari Devi, the young widow of Roy’s elder brother, was burnt alive. They forced her to drink bhang before they led her to the pyre.” That was 1811, 176 years before Roop Kanwar, the last sati of India.

Deep inside the grove are the remains of the house Roy had built for himself when his father disowned him following his public critique of Hinduism. Through the broken pillars and arches, I can see couples chatting, clicking selfies, playing hide and seek. A young woman laughs out loud making two crows start and fly away.

No, Roy would not be entirely disappointed.