The deep pleasure in watching the West Indies square off against England at Southampton was strange because international cricket hadn’t been gone that long. It was less than four months ago that the English tour of Sri Lanka was cut short in the middle of March. No, it wasn’t a lengthy absence that made the match at the Rose Bowl such an event; it was the simple joy of watching one of the swallows of a sporting summer, Test cricket in England, take wing in this Covid-stunned world.

There had been uncertainty about whether the West Indian tour would happen at all. Once it was confirmed, England’s cricketing press saw it as a tune-up for bigger contests later in the year. The West Indies have been cricketing minnows for more than a decade now and this English team, having won the World Cup and heroically drawn the last Ashes series, is a powerhouse. The tourists were weakened further when three of their better batsmen made themselves unavailable. Geoffrey Boycott suggested that England’s selectors use the tour to blood young batsmen.

Then, suddenly, the series opener acquired a resonance that seemed to come from outside of cricket. The aftershocks of the campaign against racism provoked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis had reverberated across the Atlantic. The statue of a slave-trader had been pulled down in Bristol and unceremoniously drowned. Cecil Rhodes’s smaller-than-life figure in Oriel College seemed destined to fall after the college’s fellowship voted for its removal. Keir Starmer posed stiffly for a photo while ‘taking a knee’. The Daily Telegraph harrumphed about how hard leftists had captured Black Lives Matter (the organization) and thus ruined Black Lives Matter (the cause). A spokesperson at 10 Downing Street made it a point to tell the press that Boris Johnson and his cabinet had not participated in the minute’s silence in Westminster against racism and police brutality.

In the middle of this came the news that the two cricket boards had agreed to pay homage to the BLM cause by taking a knee before the first Test began. Cricket’s dovecotes began to stir. The English Premier League’s embrace of BLM has deep roots, going back to the Kick It Out campaign against racism in English football that began in 1993. But the English cricket’s establishment isn’t just snow-white in its composition, it has, as Barney Ronay pointed out in an article in June, consistently embraced players, coaches and administrators who aided and abetted apartheid. Mike Gatting, who captained a rebel tour to South Africa and has never expressed any contrition, became president of the MCC and is currently employed as a ‘cricketing ambassador’ by the ECB. Geoffrey Boycott, another ‘rebel’, is now a knight. In a cricketing culture as blinkered as England’s, the news that the ECB had agreed to publicly perform ‘wokeness’ set off conniptions. The Daily Telegraph surpassed itself by running a parody-proof header: “Cricket should not associate itself with the offensive policies of the anti-semitic anarchists who run BLM.”

On the morning of the Test, the West Indian dressing room was decked with a banner that juxtaposed the team’s logo with a roundel printed with ‘Black Lives Matter’ in capitals. Before the first ball was bowled, everyone in the middle took a knee (including the umpires), and every West Indian player raised a black-gloved fist as well. For a brief moment, that pose, at once militant and moving, became a summa of the struggle of black athletes and their allies against racism. It invoked Tommie Smith and John Carlos and Colin Kaepernick, of course, but also cricket’s own redeeming cause, the sanctioning of South African apartheid. The shades of Learie Constantine, Frank Worrell, Clyde Walcott and Everton Weekes (who died recently) would have approved. So would the ghost of C.L.R. James, historian and socialist, who showed us how cricket became a vehicle for black self-assertion in Beyond a Boundary, the greatest book in the game’s canon.

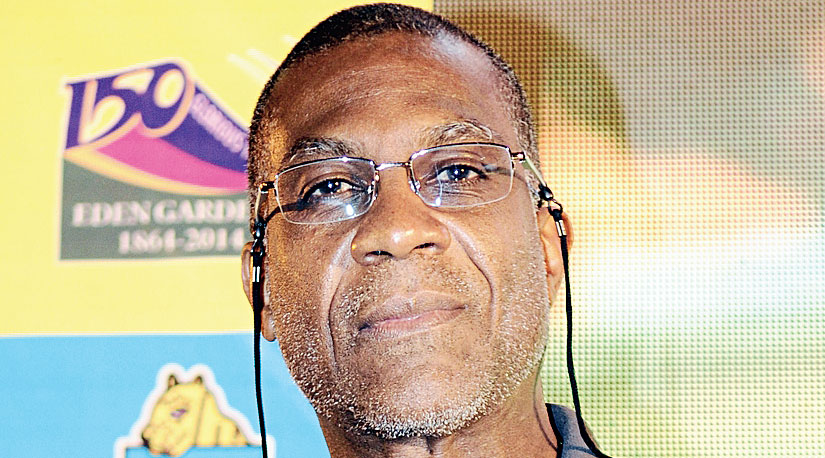

It’s not an accident that Tommie Smith and John Carlos and Muhammad Ali and Colin Kaepernick have helped to define and shape the anti-racist movement. There is something about sporting excellence that compels admiration. When an athlete you admire bears witness to bigotry and discrimination, it’s hard to be dismissive. On that first day, when Michael ‘Whispering Death’ Holding used his commentator’s perch as a bully pulpit to tell us why black lives mattered in an inspired, off-the-cuff homily, people listened. The next morning, every newspaper in England (including the BLM-loathing The Daily Telegraph) wrote reverentially about the legendary fast bowler’s great opening spell.

Given this build up, the cricket that followed could have been catastrophically anti-climactic had it followed the formbook... but it didn’t. Ben Stokes won the toss and decided to bat on an overcast day. His counterpart, Jason Holder, leading a four-pronged pace attack, cleaned up England for just over 200 runs in a style that Holding would have recognized. At close of play on the second day, England had conceded a first innings lead of 114 and the West Indies had given themselves every chance of winning the match. They performed like a team determined to rise to the occasion, to live up to the match’s framing moment.

Growing up in India where people of African descent were routinely called hubshees or, as Darren Sammy more recently discovered, kalus, watching Sobers, Hall, Gibbs, Lloyd, Greenidge, Richards, Roberts and Marshall play, was a lesson in colour-blind fandom. The English were the enemy and since India lost more often than it won, the summary way in which West Indian teams dealt with English sides was peculiarly satisfying. When Tony Greig promised to make the West Indians grovel at the start of the 1976 tour, Vivian Richards and his team mates weren’t amused. Richards with the bat and a young Holding with the ball pulverised England 3-0 in that five Test series. The last Test at the Oval was a kind of massacre. Richards smashed 291 and Holding racked up 14 wickets to record the best-ever performance by a West Indian bowler in a match. In India, we read accounts of the thrashing in the sports pages and resonated like tuning forks to their brutal music.

Champion West Indian sides taught my generation of cricket-mad Indians to love and admire black players. They showed us by example that black lives mattered before the phrase existed. They were an antidote to the casual racism of the time; they were often the first progressive influence that Indian schoolboys encountered. But I also loved them like a needy desi for letting me live, second-hand, their English triumphs. When Holder and his men took a knee in Southampton, and then took lots of English wickets, I felt an exhilaration that was both politically kosher and cheerfully base.