A vital debate is raging across India and across the India that lives overseas, particularly in the United States of America. What makes people and nations fulfilled? Work or relationships? Labour or culture? The professional or the personal? This is a formulation where the personal and the professional must exclude each other. It is a definition of labour that eliminates the work of culture, or the work of communities or relationships. Limit your definition of work, therefore, to the materially productive and the swiftly profit-generating in the free market. What is the combative importance of such work against the wasteful training to become athletes and prom queens? Or staring at one’s partner on weekends?

The debate arose, as debates do these days, with provocative comments made in the media and on social media. The American politician, Vivek Ramaswamy, cast the opposition between productive labour and recreational culture in a clear binary: “A culture that celebrates the prom queen over the math Olympiad champ, or the jock over the valedictorian, will not produce the best engineers.” The poorly disguised reference to the STEM education excellence of Indian immigrants and their children — Ramaswamy’s own social group — triggered a spate of racist anger from the White right-wing that is Donald Trump’s voter base, shaping its own life and spectacle in the Trump-ant America that was formally inaugurated day before yesterday.

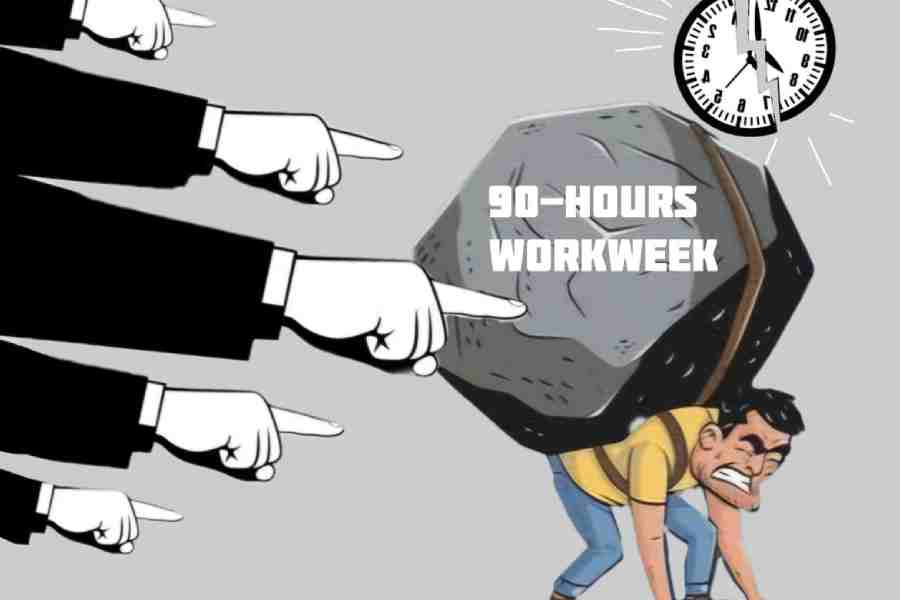

In the meantime, recreation and leisure have been vilified in favour of a productive corporate culture right here in India. The chairman and managing director of Larson & Toubro, S.N. Subhrahmanyan, called for an expansion of the workweek to 90 hours per week. This was destined to be provocative, coming not too long after the Infosys founder, N.R. Narayana Murthy, called for an expansion of the work to 70 hours per week, just as the four-day workweek dawns across patches in western Europe, North America, and Australia/New Zealand. Pungency was added to the provocation by Subhrahmanyan’s bizarre comment that employees should come to work on Sundays rather than spend it ‘staring at their wives at home’. The sexism of the remark recalls the recent attempt at witticism by the industrialist, Gautam Adani: while spending four hours daily with family is a good idea, if one does that for eight hours every day, the wife will run away — “toh biwi bhaag jayegi!” The choice between work and personal life is also inevitably gendered, where the onus is always on the man.

These quotable quotes have broken the internet and sent spasms through social media. It’s easy to miss the fact that they point to the most fundamental questions about personal happiness, the building of communities, and the formation of nations and national images. At the same time, they raise questions about the production of economic value, profitable employment, the competitive edge of countries, companies, and markets. All overarching concerns that shape the lives of individuals and nations.

Together, they rephrase that classic question: What is a good and meaningful life? As well as a modern one: What is progress?

Modern markers of humanity as well as productivity derive from watershed moments in European history — the Renaissance and, more crucially, the Enlightenment. These markers include reason, science, technology, capitalism, the modern nation-state, even conceptions of individualism, privacy, and interiority. These yardsticks of human progress, globalised through colonialism, have long since made the world beyond the West look lazy, unproductive, and primitive. Tropes of the lazy Black, the backward native, have thrived — quickly called lazy and backward when not working hard on plantations and factories and supporting Western capitalism. The story of wealth-production on the back of Empire, economic neocolonialism and the consequent construction of ‘progress’ is well-known to anyone who has studied history with a critical eye. But it’s also impossible to deny the skewed position of decolonised cultures on the quest for modernity, through crime and corruption, the violation of democracy and human rights — be it the highly unequal societies of South Africa and India, or repressive regimes in the Middle East and Latin America.

Immigration changed the narrative in intriguing ways, particularly when it became voluntary and got coupled with education and professional aspiration — as in North America after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. People with aspiration and talent (often nourished and reared by their birth countries), moving from the Global South to the Global North, enacted a culture of work, merit, and productivity that upset their traditional positions in the North-South hierarchy. This was most sharply evident in immigration from Asia to Europe and North America. While the former placed strong value on education, particularly in science and technology, the latter offered greater access to the free market and accompanying personal freedoms that were far scarcer in the hierarchical and authoritarian cultures of Asia. The upset equation of these values is the context of the American debate — while the still-uneven import of corporate capitalism to India is the context to the second debate.

As sobriety returns to the name-calling, hashtag-hurling rounds of acrimony, realisation also returns that the actual debate is about the quality of work, not its brute volume. And the true quality of work mysteriously loops back to the true quality of life. Headway in industrialisation, progress, and technology has increasingly removed humanity from basic forms of labour, particularly in capital-intensive economies that have spurred this debate, even though the scenario remains starkly different in labour-surplus economies that still define this country. In the former context, it is no longer enough to work hard — it is more crucial than ever to work smart.

For the natural yet shocking conclusion to the advances in productive labour is that of Artificial Intelligence that may very well take over a good deal of these projected 70-90 hours. As it does so, humanity will be more pressed than ever to find new ways of creating value, or redefining value altogether. In that great artificial atmosphere, economic value will have far lesser cause to fight the human value of life, for that may be the only kind left to us.

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent book is The Amateur: Self-Making and the Humanities in the Postcolony