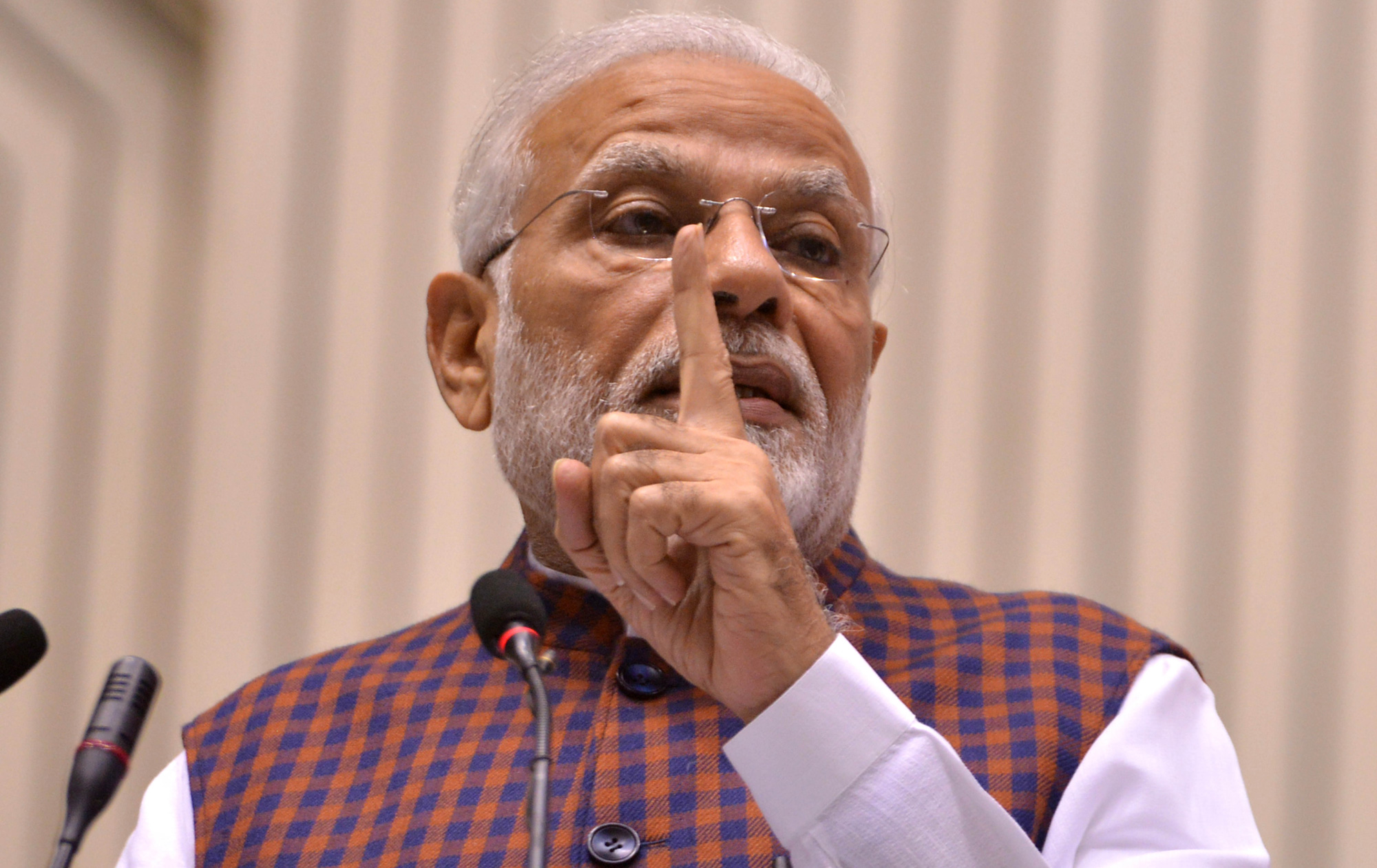

One of the first public acts of the Narendra Modi government after the Bharatiya Janata Party lost the three assembly elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan was to reduce the goods and services tax on a clutch of items. The move was quietly welcomed in all circles — including the Congress that said it had suggested it first — but there was also a corresponding feeling that the move had come too late to shake off a growing impression that the Modi government was fast losing its momentum. Indeed, if the buzz in Opposition circles is any indication, there is an emerging consensus that the BJP may not reach the majority mark in next summer’s general election. The speculation in Lutyens’ Delhi centres on whether the BJP by itself will cross the 200-seat tally. Of course, there is no corresponding agreement over what or who will replace Modi.

Writing premature obituaries is always hazardous. The consensus prior to 2009 was that the days of the United Progressive Alliance were well and truly over. This was broken by two factors. First, the unexpected departure of Naveen Patnaik and his Biju Janata Dal from the National Democratic Alliance, an exit that put a big question mark over the ability of L.K. Advani to emerge as the next prime minister. Secondly, the frenzied nationwide campaign by Mayavati, the then chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, to project herself as the third front alternative. More than anything else, this aggressive — although ultimately ineffectual — campaign by the Bahujan Samaj Party chief had the unintended effect of invoking widespread fear of political instability and contributed immeasurably to securing support for the UPA, particularly the Congress, in urban constituencies. Apart from the BJP, the Left parties were among the casualties.

No historical precedent is ever faithfully replicated. It is entirely possible that after five years, the grim memories of a coalition government that struggled to take difficult decisions owing to competitive political pressure — including from within the Congress — may have faded. Additionally, the horrible experience of the two United Front governments may have faded entirely from the collective imagination. This may be a reason why quasi-scholastic articles upholding coalitions as representative of India’s diversity are often to be found in the media. The underlying rationale is that the BJP and Modi must be prevented at all costs from having another five-year term at the Centre.

It is instructive to explore some of the reasons why a section of the elite is unduly anxious to secure a change of government. Just before and just after the BJP under Modi stormed to power in 2014, the fear was that such a government, without the restraining influence of the benign Atal Bihari Vajpayee, would transform the very nature of the polity. Fears were expressed that majoritarian impulses would see minorities cowering inside their ghettos and there would be tampering with the Constitution.

Despite the strictures against beef and the handful of excesses by cow-vigilante squads — functioning, it should be added, without any official sanction — the social fabric of India has not really undergone any meaningful change since 2014. Yes, there is now some measure of official patronage for yoga, Sanskrit scholars don’t feel completely marginal in universities and a greater willingness of Hindus to assert their Hinduness without fear of inviting social condescension. Some academic institutions have also witnessed changes that invariably come about with changes in government. But there has been, for example, no saffronization of education in the same way as there was a red takeover of education in West Bengal under the Left Front. The anticipated changes in history books, too, have not materialized, much to the dismay of some saffron revisionists. As for institutions, the judiciary is today more powerful than it has ever been, the Constitution is firmly intact, the Election Commission robust and the Comptroller and Auditor General’s office spared of controversy. The controversies over the Reserve Bank of India are, of course, real but they involve genuine disagreements over liquidity and interest rates, issues that don’t jeopardize the much-touted Idea of India.

The Modi government has witnessed profound changes in governance. There has been a greater reliance on technology and a greater emphasis on delivery. Some of the schemes, such as direct transfer of subsidies to beneficiaries and the road building and power generation programmes, have yielded fantastic results and others less so. Indeed, Modi has been criticized for emphasizing incremental shifts and managerial efficiency, rather than promoting systemic shifts in favour of a minimalist State. Modi has not emerged as a doctrinaire Margaret Thatcher. Indeed, if he secures another term, he will be best remembered for complementing economic growth with social welfare. If successful, the Ayushman Bharat health programme will be a landmark achievement.

So what explains the quantum of visceral hate — as opposed to normal disappointment that often creeps in with governments —against Modi?

The first has to do with the decision-making process. If there is one thing that marks the Modi government from its predecessors, it is the fact that it has shown that it cannot be pushed around. Normal political resistance to specific legislation — as with the land acquisition bill and the citizenship (amendment) bill — is understandable and a part of democracy. But what has invoked the ire of a small section is that the government is remarkably insulated against discreet lobbying by interested groups. Delhi used to be at the centre of a lobbying industry dominated by fixers who could get decisions moulded in a particular way. That is now a sunset industry, desperately seeking a rehabilitation package with the return of the ancien régime.

Secondly, while the demonetization of November 2016 may be contested, Modi’s big achievement is that he has, for the first time since 1947, rolled back the tide of corruption. There is a quiet acknowledgement that while lower-level corruption may still be rampant, corruption in high places involving the government has virtually come to an end. Modi’s role as a strict disciplinarian may be resented in quarters used to permissiveness but it has resulted in the government steering clear of anything smelling of irregularity. The Congress tried to reverse this impression by creating a furore over the purchase of Rafale aircraft from France. But, as the Supreme Court verdict showed, there is nothing remotely irregular involving the government. As of now, the taunt that the chowkidar has turned a thief doesn’t carry credibility beyond the circle of those who loathe Modi for reasons other than dodgy integrity.

Finally, Modi has effected a fundamental social shift in the global role of India. Previously, despite occasional bouts of muscle-flexing in the neighbourhood, the tone of Indian foreign policy was governed by the principle of niceness. Under Modi, this has been replaced with hard-nosed calculations based on the promotion of national interests and building the foundations of a future when, with greater economic advancement, India can play a more active global role. Thus, we have witnessed a deepening of ties with some of the wealthier Arab states being complemented by a more uninhibited relationship with Israel. With Pakistan, following unsuccessful attempts to reach out, India’s policy is more muscular and encapsulated in the principle: if you cause pain to us, we will answer by inflicting greater pain on you. No wonder Pakistan is awaiting a regime change in India. Then there is the conscious incorporation of the Indian diaspora as unofficial ambassadors of India.

Maybe it is not Modi’s sole contribution, but today carrying an Indian passport is not associated with the same disabilities and suspicions it once was. It is indicative of a larger but quiet change India has witnessed.