Someday very soon someone will commission a poll on who will be India’s preferred pick for prime minister in 2019, and the answer won’t be worth either the wait or the bet. It will be the same man who has consistently led such polls since 2013 or thereabouts: Narendra Damodardas Modi. His most credible emerging challenger, Congress president Rahul Gandhi, will probably have added a few percentage points to his lapel but the overwhelming odds still are Modi will re-emerge frontrunner by a fair distance.

There doesn’t exist in the field yet a politician that can match Modi on vital counts — reach, resources, energy, focus, impact; the ability to intervene and disrupt and, very often, cynically and dangerously distort for political purchase; a flair for communicating to his constituency with things said and left unsaid; a whetted, and occasionally diabolical, determination to retain grip on his reign. Modi is a consummate and unsentimental power creature like no other about. He hasn’t come under the lee of last week’s reverses suffered by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), he continues to loom over them, still quite a raved, even ravished, reputation.

But here’s the thing about reputations and public ravishment with them: they tend to quickly unravel, and sometimes they unravel without revealing upon the victim the approaching fall of fates. As happened to Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2004, arguably the Leviathan of that time but one who had begun to gloat on the notion that he had conjured a Shining India. Or as happened to the Janata Party, so euphorically elected in 1977 as rap and replacement to Indira Gandhi and her excessive Emergency; the Janata jubilation soured so quickly and wholly, the widely despised and dethroned Indira Gandhi was brought back to power in 1980. Or even as happened to her son and successor, Rajiv Gandhi, who still holds the record for acquiring the largest-ever Lok Sabha kitty in 1984. It all got frittered in the space of less than a term; by 1989 India’s first pin-up prime minister had come unstuck. When the ground beneath shifts, the first it fells are those that stand tallest on it.

There will, justifiably, be arguments over whether or not the ouster of BJP governments in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh reflect on Modi, and if they do, to what degree. Modi, after all, was not a contender anywhere. Several reports off the field suggested that despite the adverse turn of public mood towards incumbents in the states, Modi himself appeared unaffected, that this was a local vote driven by local factors; the 2019 vote, with Modi at its centre, will be quite another in nature. Presidential, if one word can sum it up; if not Modi, WHO?

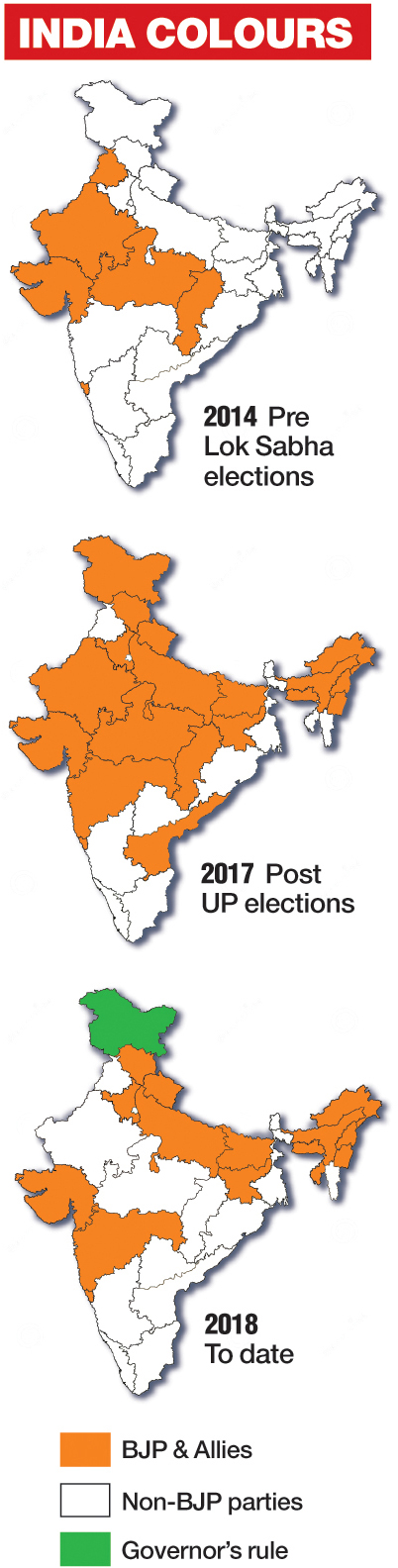

What there can be little argument about are a few other things that might also come to bear on the outcome of 2019. The first among them is this: a large chunk of the Indian heartland has now slipped under Congress rule and all of its governments will be freshly incumbent by the time Lok Sabha elections are held; power lends you key levers and in the three states the BJP just lost, those levers are with the Congress. For a party like the Congress, whose rank and file had turned infamously demotivated since 2014, three chunky handles on power will also likely mean an injection of energy and self-belief at the organisational level. At the leadership level, Pappu has already begun to fluster the authors of that moniker. And Pidi is no longer yelping or barking; Pidi just bit, not once but thrice. Rahul Gandhi is beginning to deliver what few reckoned he ever was capable of delivering: electoral victories and the shoots of a sense that Indian politics isn’t the unipolar deal that Modi’s raucous cries of “Congress-mukt Bharat” and BJP president Amit Shah’s claims of “ruling another fifty years” had begun to suggest to some. That question has been resoundingly asked as counter-echo to There Is No Alternative (TINA): Is There No Alternative (ITNA) ?

The Modi-Shah duo has suffered reverses earlier, in Delhi, in Bihar, in Punjab, in Karnataka. But this may be different. This is about a piece of real estate the BJP believed to have exclusive rights over, its core ground, the Hindi-speaking, overwhelmingly Hindu cow-belt. And the loss of it has arrived far too close to the 2019 contest.

There are yet more things there can be little arguing with. Up close to the end of Modi’s term, rural/agrarian anger swirls about its pocket-borough patch like never before, and the blame for that must lie at the Centre’s door much more than it lies with state governments. Seventy or more per cent of the populations of states the BJP just lost live in villages and depend on land — its produce and the buying power it generates or does not. The losses for the BJP in rural belts has been stunning as a slap. Thirty four per cent rural seat-share losses in Chhattisgarh, 30 per cent in Madhya Pradesh, 49 per cent in Rajasthan. Those numbers turn darker when set in a Venn diagram to depict the overlap with the desertion of SC/ST votes. The BJP lost more than 61 lakh votes in just those three states; the Congress gained close to a crore and a quarter. A projection — purely mathematical as opposed to political, it must be emphasised — suggests the BJP stands to lose as many as 44 Lok Sabha seats across this geography.

The ground was adverse, angry. Which brings us to another, and probably critical, issue not many can argue with: Modi’s inability to turn things around this time. It’s what the BJP has come to invest great faith in — the knack Modi has of landing in the midst of a tough battle and extracting victory from the jaws of defeat, of turning things around single-handed, of turning the public mood with his oratory, of unleashing a surge of energy nobody else can. The Prime Minister barn-stormed the battlegrounds aggressively and provocatively, but he could not swing it. Whether the razor verdicts of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan were achieved because Modi was able to push and spur with his rallies or whether it was down to how popular local leaders like Shivraj Chouhan remained is a matter the BJP will best grapple with internally, but on the outside the patent truth is Modi could not make a significant difference.

What can he do to intervene more decisively in the coming months, as he has often done in the past? Does he have a record to boast of, feathers to pin into his flamboyant pugrees? On the evidence of the campaign he just finished, there exists a poverty of positive talking points in his quiver. In the absence of credible claims he could make, he chose to rely on blame, on attacking the Nehru-Gandhis in particular. He often sounded surreal, as if they were still in saddle and he were launching into battle against the Nehru-Gandhi establishment. He no longer brags about demonetisation or GST, aware that the widespread verdict on both is palpably negative. The hope he generated in 2013-14 has turned to heated hype paid for mostly by the public exchequer. His fancy flagship initiatives have barely gone beyond claims and sloganeering. Unemployment is soaring, purses across the nation are pinching. (Or, it could be argued that farmers don’t carry purses.) Key institutions he has turned to a shambles over the course of his reign — Supreme Court judges found themselves compelled to call an unprecedented press meet and raise alarm over executive interference, the Reserve Bank lies wracked, the CBI is controversially riven and headless, the Central Information Commission has complained of manipulation, the armed forces, well they have never ever before been encouraged into overt ultra-nationalist political discourse as today.

Modi did play hard at his default mode on the side — Hindu Hriday Samrat. He commandeered the VHP-Bajrang Dal and UP chief minister “Yogi” Ajay Singh Bisht “Adityanath” to wage battle for him. The VHP-Bajrangis renewed their oaths to a Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, and were volubly endorsed by Shah and Ram Madhav. Bisht himself choppered about the campaign, addressing 74 rallies at reliable count. He had come from lavish Dussehra celebrations and the renaming of Faizabad as Ayodhya. He had come from rococo declarations of erecting a lofty Ram statue. He spouted such gems as calling Hanuman a Dalit; we know the Dalits were hurt, we haven’t heard what Hanuman thought of it. He forsook Ali for Bajrangbali. He wanted Hyderabad changed to something that few Hyderabadis had ever heard of. The BJP lost wherever he went.

When the public mood turns averse, not even God can help, much less the fabled poll mechanics and machineries Shah has put in place. Democracies live by another god, goes by the name of Voter.

PS: If it at all is an aid to perspective, India’s first cow welfare minister, Otaram Devasi, lost to an independent Congress rebel from Sirohi district in Rajasthan.

Graphics: Sabyasachi Kundu