Today, the sense of inevitability and the inexorableness of the Narendra Modi regime are obvious. It is strange to observe people recognizing a touch of Modi in them and confessing, almost quietly, that they were members of shakhas as students. Modi, to each of them, becomes a touch of nostalgia and a fragment of normalcy. A man once framed as outrageous now plays the next-door neighbour, benign, wise, someone whose qualities you took time to recognize. People even add that five years of rule have converted him from politician to statesman, adept at global governance, a companion to Shinzo Abe, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. Many Indians feel proud that Modi is shoulder-to-shoulder with these international figures. Indians feel a vicarious pleasure in such a status. We claim that we have arrived in the global world. One senses this smug satisfaction, this sense of celebration, as we traverse every newspaper today. The mass media has abandoned its sense of critique. In a spineless way, it has devoted its editorials to policy analysis and sociological comment, distancing itself from academic debates, allowing retired bureaucrats and think tanks to play second fiddle to current policy. It displays a voyeurism about power, which is tempting to psychoanalyse. Instead of critique, we have a chain of endorsements that might even embarrass the proponents of the regime.

However, while this festival of acclamation is widespread and the defeated parties are accused of playing sour grapes, one needs to take a deeper look at the polity.

A majoritarian government carries both the electoral halo of democracy and the vehicular competence of a totalitarian regime. Its numerical presence erases the power of rebellion, resistance or opposition. There is nothing as comic as the Opposition today. Except those who stick to vernacular politics satisfied with local control, the Opposition has cut little ice nationally. The Left is almost autistic in defeat, displaying its ineptness at both revolution and resistance. The Congress still presents a brooding picture of adolescence, pretending to be playing boy scouts at war.

Given the collapse of the party as opposition, given the general acclaim of the middle class for Modi, patriotism becomes an epic caricature of conformity. We have not only to agree, but be seen to agree. The very idea of uniformity becomes a visual performance where the crowd as a yea-saying chorus and the mob as an obsessive lynch squad are not very different. Populism and majoritarianism combine to create an epidemic of conformity, which is surreal to watch. Dissent is now seen as a perpetual act of pathology that every loyal citizen wants to exorcise. The NRI playing the citizen away from home is even more Modi-esque in his behaviour. Every breath he takes is presented as a loyalty count to the regime.

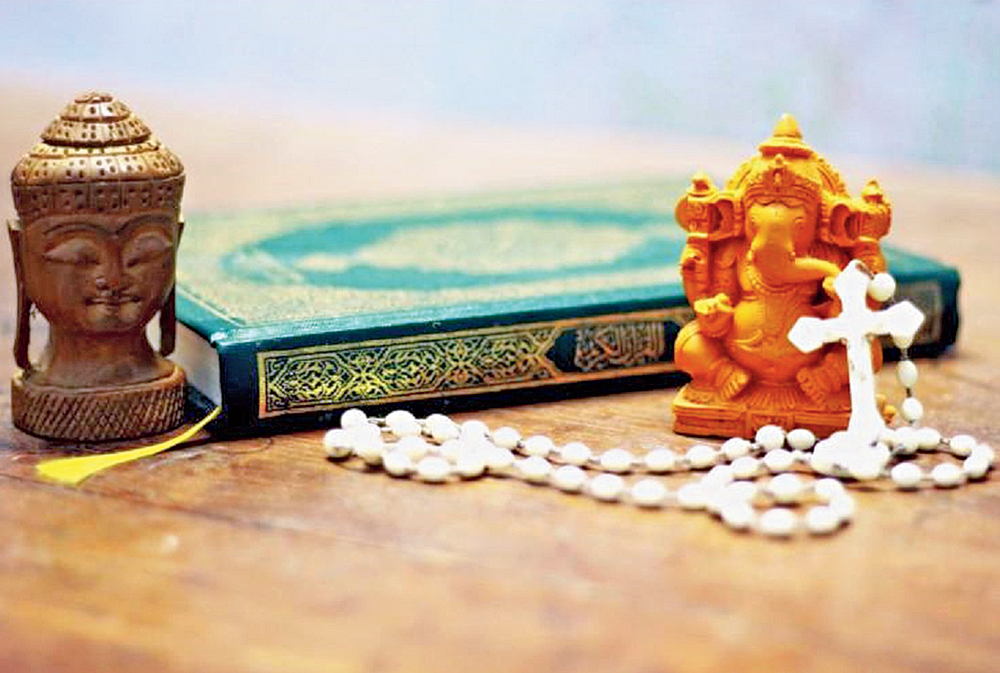

The picture from the dissenting side thus becomes surreal. It is almost as if ideas in India march in uniform and the diversity of our culture displayed civilizationally is forgotten. Sadly, it is at the spiritual level that the response to the regime is most abject and instrumental. Our spirituality at the popular level has, like Modi’s model of development, become managerial, a question of technique rather than a search for holism and meaning. The pathetic display of conformity on International Yoga Day has diminished yoga as a spiritual exercise, reducing it to a set of techniques. Yoga gurus have acquired a new respectability, a sight which would make any Bhakti movement pause in embarrassment. Modi is now seen as a secular Vivekananda, making one wonder what Bengal’s spiritualism and cultural renaissance was about. Today, there seems to be little difference among spirituality, plumbing, management and politics. In fact, the CSR of corporations pretends to be a source of sustainability, adding to the hypocrisy of development. As a Jesuit teacher told me, “CSR is one of the most pathetic oxymorons of the day, reflecting the current plight of ethics. In fact, one of the first consequences of conformity is a sense of mediocrity, a vociferous denial of alternatives, plurality, or the sense of the complexity of the everyday. Pseudo-spiritualism has overwhelmed the pseudo-secularism of the earlier era.”

The real challenge today is at the level of civil society. Yet, civil society has become the biggest casualty of the Modi regime as a result of its persistent efforts to belittle the dissenting power of the non-governmental organization. The breakdown of the NGO has been at three levels. First, NGO dissent has been repeatedly read as anti-national. Yet, realizing the power of the NGO, the Bharatiya Janata Party regime has created a mimic civil society around the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Bajrang Dal, where civil society pretends to be a serious extension of the State. This mimic civil society is one of the first challenges for a resurgent civil society as part of a democratic, rather than electoral, imagination. The other casualty of electoral majoritarianism has been the minority, the margin and the dissenting imaginations. The mainstream is almost convinced that the search for alternative imaginations and plural worlds is a puerile, if not futile, exercise.

The challenge before civil society is to extend the idea of civil society to a global scale where civil society and the dialogic sense of civilization can combine to challenge the arrogant predictability of the nation state caught in the procrustean vocabularies of development, security, border and models of economics which show little sense of ecology or the epistemic violence of the policy sciences. Secondly, ideas of the vernacular and the region have to combine to create a more playful sense of pluralism. Thirdly, since the regime has seceded from the future in its obsession with a fictive past, the future must become a source of alternative and dissenting imaginations as it did during the struggle against Stalinism and authoritarianism. We have to realize that we may not have crystalline paradigms, but we do have great exemplars in M.K. Gandhi, Bishop Tutu, Raimundo Panikkar, Ivan Illich, Václav Havel, allowing us a range of possibilities to combine the ethical and the political in a new pallet of dissenting imaginations.

One of the first things civil society has to do is to adopt Gandhi’s model of Swadeshi and Swaraj. Here, politics combines the local and the vernacular with the planetary and the civilizational, challenging the limits of the global paradigm. Nature now becomes a part of the constitutions the way the Maoris argued, but also the preoccupation with the Anthropocene, about man’s intrusion in nature, becomes central to the political and ethical act. As a result, the margins acquire a central place in our local and planetary imaginations. For example, the coastline has to be seen as a vulnerable commons. We cannot be captive to the mentalities of the current regime but think from sea to land. As a result, ecology, ethics and culture combine to create new acts of resistance where the constituency combines the margins and the future. Secondly, the frozen expertise of science is forced to be more ethical, examining new issues of suffering. One goes beyond the bandwagon of a developmental regime playing second fiddle to the corporation and the hegemonic West.

More critically, we treat democracy as an inventive possibility for every citizen, creating new experiments at every level. Dialogue as a search for difference can challenge the conformity of majoritarianism. Democracy becomes both playful and plural and citizenship loses its passive fixity, focussed on consumption and voting. The dismal science of development with its managerial pathos becomes open to new ideas, new possibilities, and alternatives become a serious act of trusteeship. As dissenting imaginations of civil society at the neighbourhood level add on the planetary scale, we challenge the poverty of the regime as an arid imagination. We literally have to rewrite a Hind Swaraj to challenge the dull modernity of the regime. Democracy becomes an exciting prospect again and this essay is an invitation to that ritual act of celebrating difference.

The author is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations