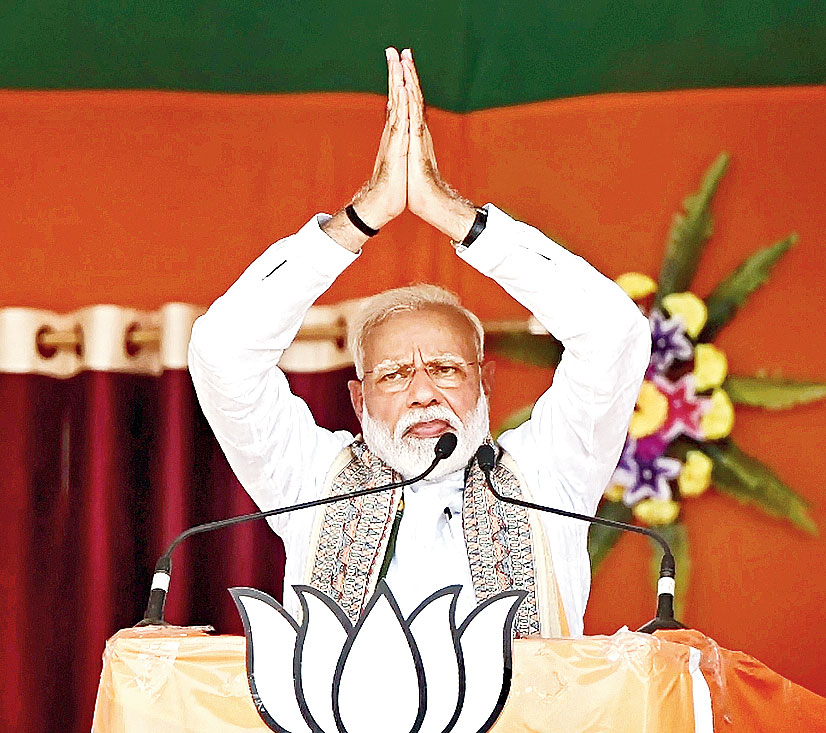

In 2014, with the emergence of Narendra Modi as a larger-than-life campaigner overshadowing his party, began the rumblings of electoral democracy in India having become presidential. Modi spoke in rallies across the length and breadth of the country, asked for votes in his own name, and where he couldn’t go, his humanoid holograms held fort. His first five years in power, characterized by a powerful Prime Minister’s Office, his direct outreach to the people through his All India Radio show, ‘Mann ki Baat’, a weak Opposition and his growing personal popularity made governance appear presidential too. Continuing with the same narrative, the 2019 election is widely seen as affirmation that the Indian electorate votes for, and expects, a presidential-style government — with sovereignty residing in a directly elected leader rather than the leader of a parliamentary party. Framed this way, it is not surprising that the Opposition failed in putting up a decent fight — with neither a united ideology nor a leader with similar popular charisma, the presidential duel was lost because only one side was in it.

While this analysis is partially simplistic, a close analysis of the actual operation of governance in India in recent times demonstrates that ominous signs for parliamentary democracy have been discernible for at least the last decade. A key indicator of the reducing significance of Parliament is the gross underuse of parliamentary time. The 16th Lok Sabha had 331 sittings totalling 1,615 hours. According to statistics released by PRS Legislative Research, this is less than half of the figure clocked by the First Lok Sabha, which sat for 3,500-4,000 hours. It is also 40 per cent lower than the average of all full-term Lok Sabhas.

Even for the time it did convene, it lost 16 per cent of its scheduled time to disruptions. This lack of productivity is not restricted to the Lok Sabha. A study by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy showed that two sessions of the Rajya Sabha spanning two different governments (Winter Session, 2013-14 and Monsoon Session, 2015) were disrupted for 72 hours each, compared to a total of only 41 productive hours across both sessions. Disruption rather than debate has become the default in Parliament, necessitating a more direct relationship between the executive and the people which is the cornerstone of a presidential system.

The clearest manifestation of such a direct relationship is the emergence of the ordinance State. During the term of the last Lok Sabha, 45 ordinances were promulgated by the president, most of the time on failure to pass a bill in Parliament. This is not a new development — the rise of ordinances as a tool for everyday governance was common in UPA II with 28 ordinances having been promulgated during the 15th Lok Sabha, with several of these being re-promulgated when the original ordinance lapsed. The proliferation of ordinances is testimony to the fact that the respect that Parliament ought to be accorded by the executive has waned to such an extent that governance now happens despite Parliament, not because of it.

The increasingly executive nature of lawmaking has also meant the rise of hand-picked ministers from non-political backgrounds, chosen from outside the party system. This is again typical of presidencies such as the United States of America where there is a real check on such appointments by the Senate through public confirmation hearings. In India, however, no such check exists — it is the Rajya Sabha that must accommodate such appointees by a political vote. Without having to go through the rigours of a general election or pass any real legislative litmus test, such appointees, despite their technical expertise, remain politically beholden only to the prime minister. This distorts the ‘first among equals’ principle that underlies the Westminster model and is much more akin to a spoils system that is characteristic of powerful presidencies.

Although each of these three indicators has been conspicuous in the last five years, it would be wrong to attribute the growth of presidentialism to Prime Minister Modi alone. The Achilles heel of every Constitution modelled on the Westminster form of government is its potential to slide into presidentialism-in-disguise when the prime minister is a more popular leader than anyone else on the political horizon. The Constitution of India is no different. When Indira Gandhi was prime minister, her ministers, erudite in their own right, were largely perceived as owing their position to her benefaction rather than to their popularity. The constitutionally mandated requirement of collective responsibility in such a system, when combined with a powerful prime minister, suggests a certain anonymity of cabinet ministers, irrespective of the reality of how deliberative the cabinet actually is.

Further, the primary constitutional check on an overweening executive is Parliament. It is here that the Constitution of India has actively pushed the country towards presidentialism through the adoption of the Tenth Schedule in 1985. Comprising provisions to prevent defection of MPs from one political party to another — the ‘Aaya Ram Gaya Ram syndrome’— the Tenth Schedule presents a gross example of constitutional over-correction. So overpowering was the need to prevent defection that the Constitution emasculated the office of the MP itself. Hereinafter, MPs could be expelled if they did not follow the whip of their political party. Inevitably, the only method of standing out as an Opposition MP became to disrupt the House. For government MPs, the effect was more insidious — a tenure of near-complete anonymity, as Parliament slowly but surely became ornamental, concomitant with the prime minister becoming presidential.

The merits of a presidential style of government can be debated, but what is of immediate concern is that we appear to have a presidential system masquerading as a parliamentary democracy. Any executive in a parliamentary system demands real checks and balances in its operation to stay committed to the public good — within the executive through the cabinet, and outside the executive through an active Parliament. If a majority of MPs owe their seats primarily to the overpowering popularity of their party leader, as is the case across political parties today, the massive investment of time, people and money that elections demand is unjustifiable. We need a real debate on how parliamentary democracy can be reinvigorated. Alternatively, we must accept that our governance system has changed and have a wider-ranging discussion on how a presidential system for India can be optimized for good governance. The country cannot remain a halfway House for long.

The author is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal.