After the era of Jawaharlal Nehru, who completed three full terms in office with relative ease, only three prime ministers have returned to power after completing a full five-year term: Indira Gandhi, Manmohan Singh and, now, Narendra Modi.

Indira Gandhi was appointed prime minister after the untimely death of Lal Bahadur Shastri in January 1966 but she faced her first general election the following year. The Congress party’s hegemony received a blow in 1967 when it lost power in several states across India. But in the Lok Sabha, it still managed to win a majority with 283 seats.

The next five years were turbulent. The famous Congress split took place in 1969, following which Mrs Gandhi took a decidedly socialist turn, marked by a series of measures such as the abolition of privy purses and the nationalization of banks. Arrayed against a “Grand Alliance” of Opposition parties in the general elections of 1971, Mrs Gandhi coined the “Garibi Hatao” slogan and rode back to power triumphantly — securing a 352-seat haul for her party.

In 2009, the unassuming and unheralded Manmohan Singh became the second post-Nehru prime minister to achieve the same feat. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, according to record books, was prime minister three times. But his first term, in 1996, lasted 13 days and he had to resign when the Bharatiya Janata Party failed to win any allies. He headed the government for two consecutive terms thereafter, but the first (1998-99) lasted barely 13 months.

Manmohan Singh, the “accidental prime minister” who assumed office after Sonia Gandhi refused to head the government in 2004, completed a full term. The Congress did not have anything near a majority in 2004, winning only 145 seats compared to the BJP’s 138. But it managed to stitch up an effective coalition named the United Progressive Alliance which secured the “outside support” of the Left parties. When the Left withdrew support in 2008 in protest against Manmohan Singh’s insistence on signing the Indo-US nuclear deal, the government managed to survive with the unexpected support of the Samajwadi Party. A year later, the Congress surprised its friends and foes alike by winning 206 seats — way higher than its 2004 tally — and resuming power for a second straight term as head of a wider coalition, despite the absence of the Left in UPA-II

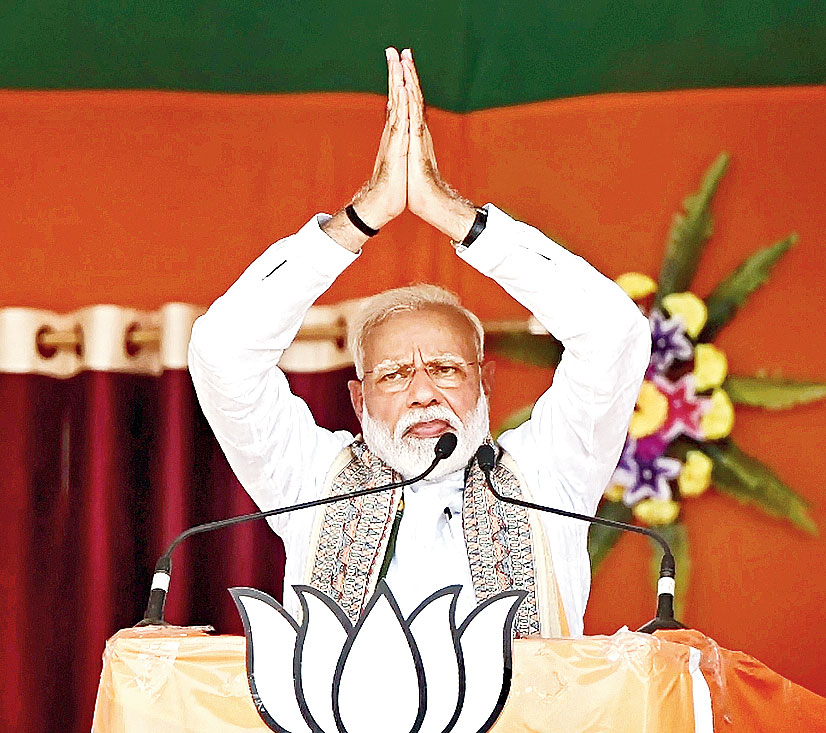

Narendra Modi, like Indira Gandhi and Manmohan Singh, has returned to power for a second consecutive term with a bigger haul of seats than his party and alliance won the first time around. We are still in the midst of the hype and the hoopla conjured up by his army of supporters and an adoring media about the “unprecedented” nature of his feat. His ideological and political adversaries, similarly, are in the throes of despair over the BJP’s back-to-back big victories.

What we tend to forget is that Indira Gandhi’s 1971 victory and the UPA’s return to power in 2009 were also hailed as great achievements, as “historic” turning points in India’s political journey. It is not just the media which made such over-the-top assessments. The victorious leaders and parties, too, bought into the hyperbole. And that, we must recall, led to over-confidence, bordering on hubris, which marred their second term in office.

Take the case of Indira Gandhi. In 1971, she won the hearts of India’s impoverished masses with her singular courage and charisma. After her victory, she cemented that appeal by winning a real war — the only unequivocal victory India has achieved on the battlefield — towards the end of 1971. But while her personal stature grew, and she became synonymous with the Congress party, her government and party weakened.

Less than two years after the Bangladesh victory, as the economy failed to create more jobs or marginal prosperity, Mrs Gandhi lost her sheen. Street protests by students and workers against corruption and joblessness began in Gujarat and quickly spread to Bihar. The veteran socialist leader, Jayaprakash Narayan, was called out of retirement by the protesting students to give leadership to their inchoate frustration against the “system” —leading to what is known as the JP movement that rocked much of north India. The Allahabad High Court verdict unseating Mrs Gandhi from office came in the midst of this turmoil, leading her to impose the Emergency — prolonging her second term in office but robbing it of all legitimacy.

The Manmohan Singh-led UPA-II did not resort to such extremes. But by the end of its second term, it had lost much of the goodwill and credibility that it had accrued in the first five years in office.

The Manmohan Singh regime did not become as haughty as that of Mrs Gandhi in the first half of the 1970s. But it too fell victim to the second term syndrome, of overinterpreting an enhanced mandate as a license to ride roughshod over the pulls and pressures of a fractious democracy. In its first term, perhaps because it was dependent on the support of the Left, the UPA government heeded voices from without and within. It worked out a Common Minimum Programme with the Left and other allies, and held regular meetings to thrash out differences and to initiate path-breaking rights-based initiatives.

After the 2009 victory, the CMP was abandoned and the Congress had little time for its non-Left allies. There were no regular meetings, no collective decision-making. The victory also made the UPA leadership dismissive of criticism levelled against the perceived corruption around coal allocations, the Commonwealth Games and 2G. Since these “scams” had taken place during the UPA’s first term, they argued, the 2009 mandate showed that the allegations had no substance. The UPA-I government’s ability to resist the global financial crisis that rocked the capitalist world in 2008 also made it less vigilant about the delayed effects of the economic slowdown on India’s economy. In the end, the complacency and arrogance stemming from winning an unexpected second term may have contributed to the ignominious defeat of 2014.

Narendra Modi stormed back to power with an enhanced majority barely ten days ago. As such, it would be premature and foolhardy to predict his future course. For one, he has far greater dominance over the polity, the media and institutions today than Indira Gandhi ever did. Manmohan Singh came nowhere close. The BJP also has the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s deep tentacles into civil society that no other party can match.

Yet, the signs of hubris and mistaken lessons from a mandate are already visible. And the clearest indication of that is the Modi 2.0 cabinet which gives a de jure status to the hitherto de facto Modi-Shah duopoly.

By appointing Amit Shah the home minister of India and the virtual Number Two in the government, the prime minister has sent out a signal that could prove damaging for his regime and his party in the long term. Amit Shah may have done wonders in turning the BJP into an election winning machine, but he lacks the appeal or the vision to be a pan-India leader that he so wants to be. Narendra Modi has the ability to assume different guises to appeal to different audiences. But Shah exudes the harshness and menace of a henchman that sit ill at ease with the requirements of the home minister of a dizzyingly diverse and complex democracy.

Shah has championed the citizenship (amendment) bill, threatened to extend the National Register of Citizens across the country, described allegedly illegal Muslim immigrants as “termites” who must be “exterminated”, and dismissed all civil liberties and human rights adherents as members of the “tukde tukde gang”. As home minister, he has the power to implement these dark and dismal proclivities.

The elevation of Shah to the highest forum of decision-making marks the end of the inner party democracy that once characterized the BJP. Nirmala Sitharaman and S. Jaishankar, members of the high-powered Cabinet Committee on Security, have no base of their own and are unlikely to challenge the Modi-Shah hegemony. Anyone who could do that has been cut down to size or removed from the new dispensation altogether.

As BJP president, Amit Shah complemented the prime ministerial outreach of Narendra Modi. Shah has often boasted that the BJP will rule India “from panchayat to Parliament” for 50 years. The bigger challenge for the vainglorious duo, perhaps, is to overcome the second term jinx...