Satyajit Ray’s 1977 film, Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players), based on Munshi Premchand’s 1924 short story, is his most complex, expensive and longest film. The story is woven around two chess addicts against the background of Lucknow under Nawab Wajid Ali Shah as his city was being taken over by the manipulative East India Company. General Outram would annex Oudh in 1856, on charges of maladministration, condemning the nawab as a “frivolous... irresponsible, worthless king” (The Chess Players and Other Screenplays, Satyajit Ray). The game of chess is thus being played at two levels that converge at the end of the film — but is handled differently by Premchand and Ray.

In an essay on Charulata, Ray explained how the demands of the cinematic medium compel a film-maker to make changes, sometimes major ones, to the literary original. Cinema has its own language and grammar that are distinct from those of the written medium. All his films, whether based on the works of Tagore, Premchand or Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay or Sunil Gangopadhyay and others, departed in design and detail from the acclaimed originals. While Ray invested them with his own vision and added new dimensions, as needed by the sensuous medium of sight and sound, he never took liberties with the spirit of the literary source.

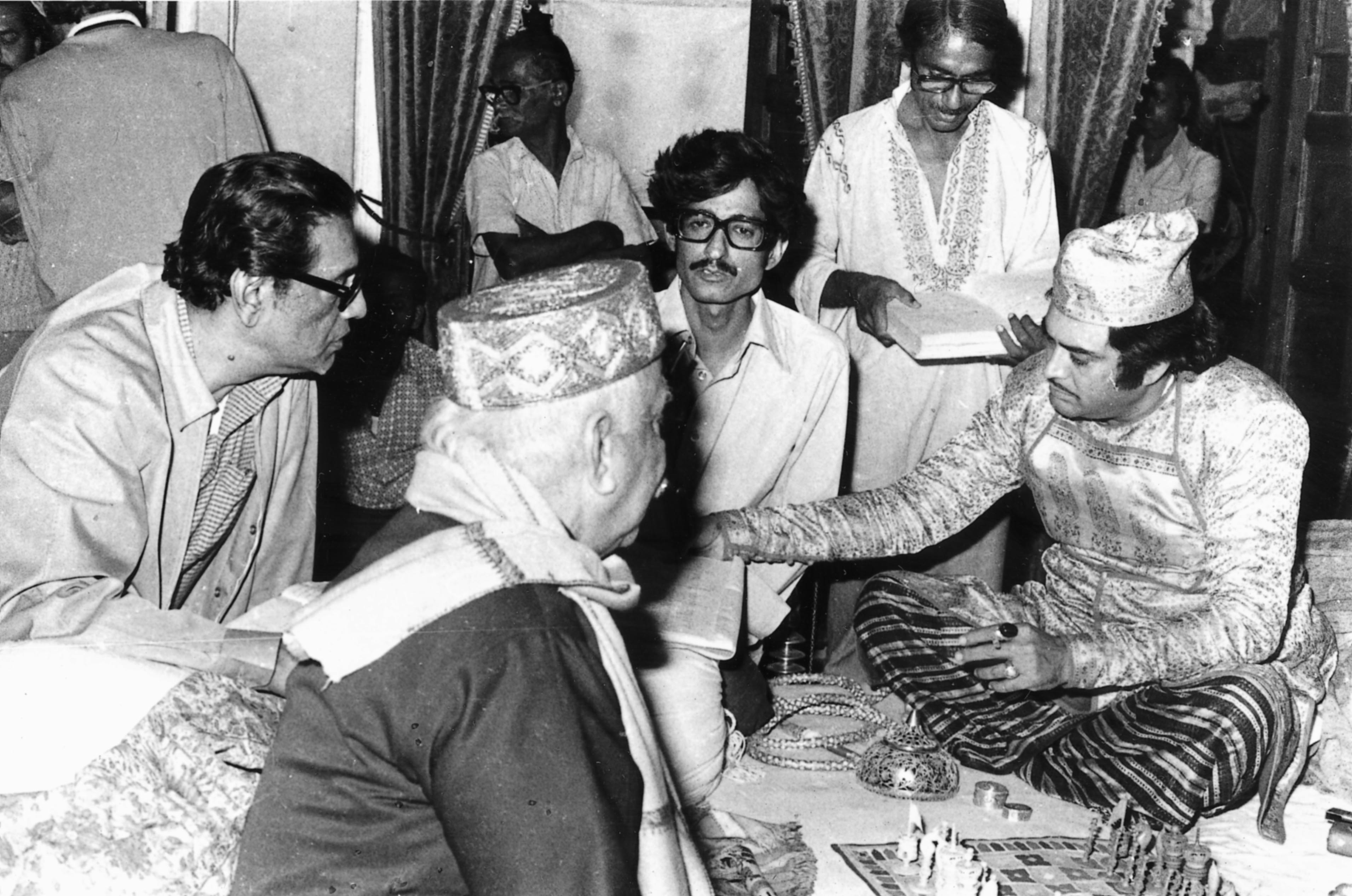

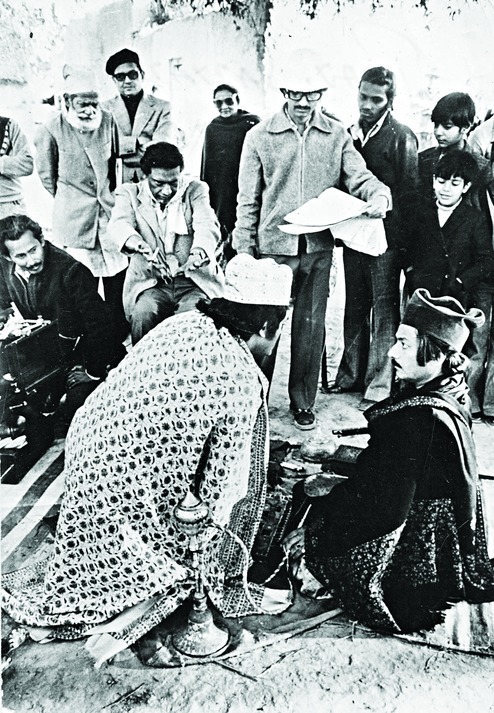

In Ray’s Shatranj, Wajid Ali Shah (played by Amjad Khan) and General Outram (Richard Attenborough) are as important as Mirza Sajjad Ali (Sanjeev Kumar) and Meer Roshan Ali (Saeed Jaffrey), the two chess-besotted noblemen. In Premchand’s original, the decadent atmosphere of Lucknow, “a cauldron of pleasures” where people “wallow” (translation by Nandini Nopany and P. Lal) serves as the canvas while Mirza and Meer remain passionately engrossed with the game. “Whole armies were lost and won — but only on the chessboard,” rues Premchand. Ray takes this story to a different level by contextualizing the issue — showing British power manipulating the self-indulgent, musically talented nawab in pursuit of its own goal. In the film, a documentary sequence, based on historical research, is interwoven with the fiction.

Master storytellers can let the power of their narrative impel the reader into imagining what remains unwritten. But the film-maker has to situate the dramatis personae in a defined space-time context. Every detail has to be worked out and arranged in a manner that is credible yet moving. For example, Premchand writes a few short paragraphs on the frustration of Mirza’s wife and how Meer’s wife encourages her husband to stay away from home. But in a film, such cursory treatment won’t suffice. Ray, therefore, had to develop these women characters in order to bring out their motives. Similarly, the introduction of a Hindu character, Munshi Nandlal, enabled him to depict the amiable relationship of the two communities. The film is full of such new characters, situations and subplots.

In Ray’s humanist oeuvre, no character is truly a villain. Both Wajid Ali and Outram, caught in a clash of cultures, are portrayed with richness and empathy. In long sequences, the two men are seen struggling to justify their course of action. The musical talent of the nawab has been given full play while Outram comes alive as a man torn between the demands of his conscience and the call of duty.

Premchand ends the story with Mirza and Meer killing each other with swords in a quarrel over the game. “These are the same heroes who, living, never shed a tear over the tragic fall of their sovereign; they are now happily dead, defending the honour of their chess vizier” (Nopany and Lal). In the film, this finish would have appeared melodramatic. Ray changed it and left it open-ended. According to him, “[T]he idea of two friends killing each other was abandoned because I felt it might be taken to symbolise the end of decadence.” The game goes on.

Lucknow falls without resistance. Meer laments, “If we can’t cope with our wives, how can we cope with the British army?” Both men admit they need darkness to hide their faces. The film ends with the “two friends playing their first game of British chess in the wan light of a late winter afternoon, as the sound of azaan mixes with that of a bugle, sounding the retreat” (Ray).

The film has been criticized for being somewhat ambivalent, with Ray taking no clear side, and its complete absence of anger. He said, “The condemnation is there, ultimately… I was portraying two negative forces, feudalism and colonialism… I wanted to make this condemnation interesting by bringing in certain plus points of both sides…”

Premchand’s story derives much of its charm from its simplicity. He is judgmental and emotional, his tone tongue-in-cheek, sometimes sarcastic, even angry. Ray’s treatment makes the film complex, multi-hued; its tone is polite, restrained, contemplative. That may account for the film’s less than enthusiastic response outside of Bengal. It is Time magazine that commented, “Ray still remains one of cinema’s best poets for a lost chance and a vanishing culture.”