While finalising the cast of Shatranj Ke Khilari, when Satyajit Ray met Richard Attenborough in London in the fall of 1976 to request him to play the role of General Outram, he told him, albeit hesitatingly, that it was a bit part. Sir Richard, who was then in the midst of editing A Bridge Too Far, said, "Satyajit, I would be happy to recite even the telephone directory for you!"

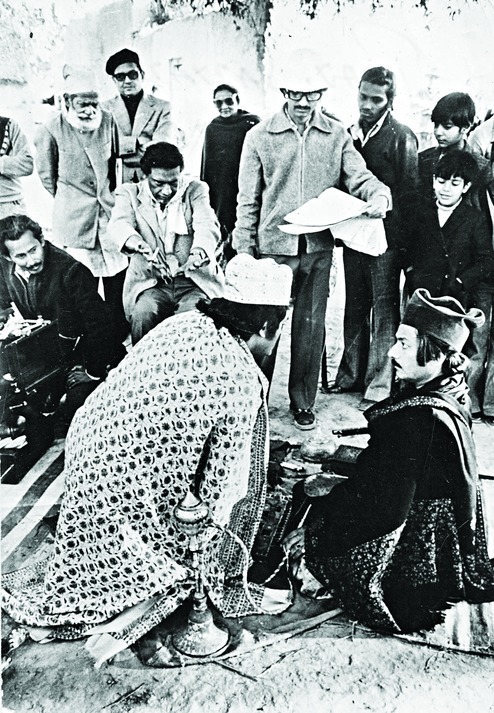

With them at the time was Suresh Jindal, producer of the 1974 sleeper hit, Rajnigandha, who would end up producing what would eventually be Ray's first Hindi film, and also his most expensive. Jindal chronicles his time with the master in a new book titled, My Adventures With Satyajit Ray: The Making of Shatranj Ke Khilari ( The Chess Players), a heartfelt account of fact, anecdote and, above all, letters Ray and he exchanged during an era when there was no email and booking trunk calls that would take hours to come through was the only way to converse across cities; in his case, Bombay, Delhi and Calcutta.

The book works as a welcome prod to jog our memories and revisit the film. Cast your mind, if you will, at the opening close-up of a chess board, cloth really. A hand reaches out and moves a white bishop. Another hand, this time from the left, moves a black knight and captures a white pawn.

The narrator lays out the pieces. It's The Voice.

Mirza Sajjad Ali, Meer Roshan Ali lad nahi rahe hain, khel rahe hain. Woh asli nahi naqli ghode daurana pasand karte hain. Tabhi shatranj jaise purane aur azim khel ko apna maidan bana rakha hai.

Much later, Biryani pasand ayi?

This time, it's Mirza mimicking his begum Khurshid, reacting to urgent summons from her from the zenana behind the chik curtains.

Then there's the cherry story in animation. The Voice tells us about Lord Dalhousie's designs on the kingdom of Awadh, Oudh in the movie after the way the English masters pronounced it.

This is a cherry which will drop into our mouths one day.

Soon after, General Outram lets it rip about Nawab Wajid Ali Shah.

We've put up with this nonsense long enough. Eunuchs, fiddlers, nautch girls and muta wives and God knows what else. He can't rule, he has no wish to rule, and therefore he has no business to rule.

Shatranj Ke Khilari, adapted from Premchand's eponymous short story, hit the screens a year after that London meeting. It was an art-house period film that received mixed reviews in India as well as overseas. Those who hailed it did so because of its sophistication, restraint and nuanced portrayal of India on the eve of the 1857 Mutiny, while the others panned it for a lack of epic sweep.

That was 1977, exactly 40 years ago. Indira Gandhi's Congress had been unseated in Delhi by the Janata Party, she having had to pay for the excesses of the Emergency; and in Bengal, months later, the CPM-led Left Front went on to win the Assembly elections that would be the beginning of its 34-year tenure in the state.

When I was taken to see Shatranj, I remember being fascinated to know that two of Sholay's key adversaries, Sanjeev "Thakur Saab" Kumar and Amjad "Gabbar Singh" Khan were in the film. In Class VII then, I confess their casting worked as an added incentive, although none of us really did need any special motivation to see a Satyajit Ray film. Amitabh Bachchan (who else?) as The Voice was a delightful surprise. The hero of Sholay no less!

Jindal's account, insightful and frank, reverential yet clinical, is a treasure trove of information and nostalgia as such remembrances usually are. He and Ray were professionally cordial all through, save the one time when the relationship soured and was on the brink of collapse. But the book is most revealing in the way the letters throw light on the working mind of one of the most influential filmmakers of our time, from discussing the cast to his penchant for meticulous research, begun as early as 1974 with countless trips to Lucknow to meet scholars.

Manik- da, how do you cast? I mean, what are the most important things you look for in an actor?

"The eyes, Suresh... and the walk. These are what tell us most about ourselves."

Sanjeev Kumar, Shabana Azmi and Saeed Jaffrey were finalised pretty early on. Ray, surprisingly, wanted Asrani ( Sholay, again) to play Wajid Ali, and Amjad's name was actually suggested by Jindal, who knew Ray had liked him as Gabbar. Vidya Sinha and Hema Malini, we get to know, didn't make the cut.

There were other more fundamental challenges. For one, Ray was venturing into a film in a language he wasn't familiar with. So he wrote the script in English and had scholars translate the dialogues in Hindi/Urdu. But the foremost concern which Ray grappled with for long was how to bring to life on screen the distinctly undramatic story of two noblemen lost in the game of chess, the prolonged sequences of silence that it would entail, and the pressing need to weave in the larger story of the annexation of Awadh, which also ended up being an act of abject surrender.

"My biggest stumbling block, however, is the growing impression in my mind that the story is intractable from a script point of view, or at best can make an arty, intellectual type of film which would put off the distributors," Ray wrote to Jindal on April 18, 1976. "...I want another fortnight to decide whether a way out of the impasse can be found. If not, I suggest that we abandon this particular project..."

Thankfully, it all worked out. Much later, responding to criticism that his film wasn't harsh enough, Ray explained his position as his biographer Andrew Robinson points out. "I was portraying the two negative forces, feudalism and colonialism. You had to condemn both Wajid and Dalhousie. This was the challenge. I wanted to make the condemnation interesting by bringing in certain plus points of both sides. You have to read this film between the lines."

Most of us did.

Shatranj Ke Khilari will always be that rare slice of distilled history, the essence of which inform our present. The "cherry", as we know it, did pop into the Angez mouth. As we watch Mirza and Meer gather the pieces to play another round of chess - remember they were at each others' throats a while ago quarrelling about social standing and a wife's infidelity - the British troops march in. It is at this moment the two strands of Shatranj meet. The ignominy of a generation that embodied feu-dal decadence comes face to face with the aftermath.

Kalloo the village boy, who had been tending to the duo with hookah and a lunch of kebab and roti, lays it out plaintively.

Badshah salamahat raajpat chhod di sarkar. Goray log hamara badshah hogua. Kouno ladath nahi, bandook kouno nahi chalawat.

You're right, Kalloo, endorses The Voice. There will be no gunfire, and no fighting. Wajid Ali Shah has given his word, and he will keep it. And three days from today, on February 7, 1856, Awadh will pass into the hands of the British.

Mirza and Meer, friends now, keep playing, having decided to head back home only after sundown. After all, they will need the cover of darkness to hide their shame.

Jab chhorh chaley Lakhnau nagari

Kaho haal adam par kya guzri.