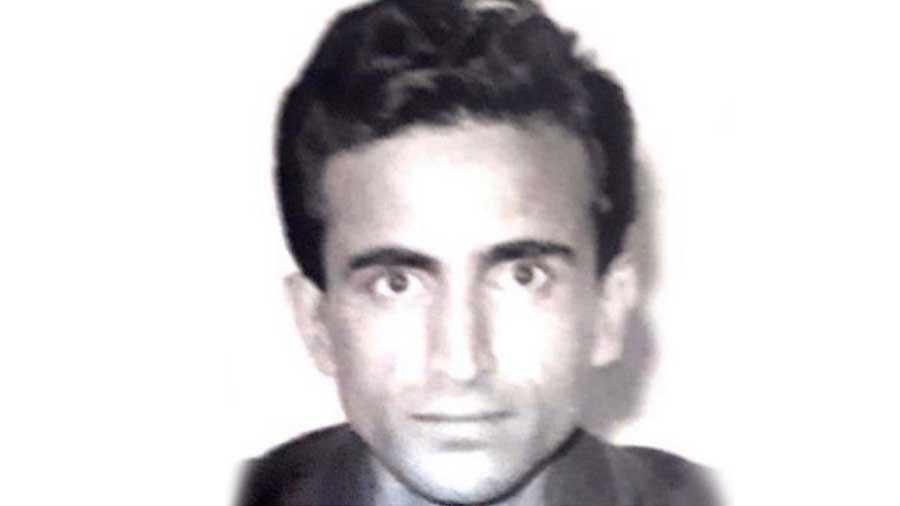

Taherbhai Chawala lived in Kharagpur in the early part of his life.

He was a ‘zaakir’ (reciter of elegies in the shaan or glory of Imam Husain).

Taherbhai would materialise in our Dawoodi Bohra masjid on Brabourne Road on the ninth night (the last of the mourning nights) of the Islamic month of Mohurrum — the eve of Aashura, which climaxed the Shiite mourning of the Battle of Karbala.

The picture: It is 7.30pm. Saifee Masjid is packed thigh-to-thigh (‘chikaar’ is the descriptive Gujarati word we used). All chandeliers have been switched on. Attendees are making small talk and waiting for the majlis to commence. Suddenly there is a hubbub. A stirring of voices that indicates that an inflection point has arrived.

Taherbhai has entered. In his golden-coloured pheta worn on the head, brown sherwani and rexine pouch containing his handwritten elegy-filled diaries. He walks from the masjid entrance towards the majlis centre. There is a ripple: ‘Chawala party aavi gayi!’ (Chawala group has arrived!).

Protocols of magic

Taherbhai, as per protocol, doesn’t just walk in and settle down anywhere he finds space; he walks with a purpose, finds the first row of the assembly allocated to all zaakirs and reaches the unoccupied spot reserved for him. He is now in front of the sadar (the person entrusted with the orderly conduct of the majlis), who is sitting facing him. He bends forward in an inverted ‘L’, does the tasleem (outward palm of the outstretched right hand almost touching the floor in front of his feet and then raised to almost touch the forehead), a sequence repeated three times, after which he stands erect, hands folded in a namaste, seeking the sadar’s permission to sit. Everything has been protocol-ed; his entry, his approach, his position, his response, his permission, his sitting down and even his posture (thighs, knees and ankles to the right of his body).

The majlis commences. The sadar permits a zaakir to recite his piece. Probably a kalam on the shaan of the prophet, the protocol (again!) by which each majlis begins. When he finishes, the sadar raises his cupped palm in the direction of the next zaakir. The zaakir acknowledges the privilege by raising his cupped hand from in front of his face towards the nose in three sequences (truncated tasleem), as if to say ‘I am beholden for the privilege accorded to recite at this Husaini majlis’).

A few recitations later, the mike is moved towards Taherbhai. Taherbhai does the same; he does an impromptu half-bend towards the sadar, acknowledges the privilege by raising his cupped palm towards his chin in gratitude. He holds his opened marsiya (elegy) diary a foot away from his face with his left hand, turns his head left-to-right and surveys the packed masjid in slow motion. He freezes the moment for a few seconds and takes his mouth closer to the stationary vertical microphone.

Silence. Until. Taherbhai. Begins. There are a few thousand people watching him.

‘Paamaal hoga dasht sitam me chaman koi, kal rann ma qatl hoga gareebul watan koiiiiiiii!’

Saifee Masjid on Brabourne Road

A batonless conductor

With these words Taherbhai takes a relatively mute majma (gathering) of a few thousand immediately to another level. The thousands — men below in the masjid, women above in their assigned gallery — begin to beat their breasts. Taherbhai has not asked them to do so. Taherbhai’s momentum of recitation has morsed to the majlis that this is a maatami noha (elegy to be accompanied by breast beating). The echo of that maatam carries 200m down an evening Brabourne Road. The pedestrian near the Tea Board senses something of a stereophonic beat but cannot ascertain where it is coming from.

Taherbhai was more than a reciter; he was a mood-creator. Taherbhai was not just a zaakir; he was a showman. He would (within the adab of the majlis) interrupt his recitation, rise and half-stand on his knees, make himself visible to the thousands, turn diagonally backwards to the right and raise his arm in an upward motion as if to say ‘Raise your maatam josh (breast-beating passion), brother!’; thereafter, he would turn diagonally backwards to the left and do the same.

In the few minutes of his piece, Taherbhai would evoke people to weep, some to shut their eyes and visualise Karbala, some to beat their breasts with impunity and some to just stare

Taherbhai was now a batonless conductor. He would use his right palm — the left would still be holding the diary — to attempt to stir the hazireen (attendees) to a desired emotion. In the few minutes of his piece, Taherbhai would evoke people to weep, some to shut their eyes and visualise Karbala, some to beat their breasts with impunity and some to just stare.

When Taherbhai ended, the mumineen (believers) would settle back, adjust their topi and kurta into some order, negotiate with their sitting neighbours for space they may have yielded and proceed routinely with the rest of the majlis. A majlis that would have climaxed was now positioned to peter out into a polite linearity.

Taherbhai recited dozens of kalaams by various shaayars that have since become an institutionalised memory for the thousands who heard him in Saifee Masjid over the decades and have now scattered across the world. There were others who possessed better voices; Kalaams like ‘Rann me luta qaafila Fatema ke laal ka’, ‘Yeh to Shabbir ka maatam hai kam na hoga’, ‘Fatema aap ke dil ko hai dukhaaya kis ne’, ‘Abbas jo nikle khaimay se’ and ‘Mehshar me Fatema ko bhi yeh gham rulaayega’. But I keep getting requests of ‘Do you have any recordings of Taherbhai?’, some interestingly from his family members. People know there are none but keep trying.

Taherbhai recited dozens of ‘kalaams’ by various ‘shaayars’ that have since become an institutionalised memory for the thousands who heard him in Saifee Masjid over the decades

Salaam to a hero

There was another side to this Taherbhai. He was a hero to all Bohra boys who went from Kolkata to IIT Kharagpur; his modest residence served as an open house to those away from home; they continue to cherish his paternal kindness. A few years ago, this Bohra IIT alumni attempted to raise funds for Taherbhai to travel on a pilgrimage to Karbala. It was their way of saying thank you. In the later years, each time I spied Taherbhai sitting anonymously in a corner in Burhani Masjid, I would take his picture and send it to the IIT Kharagpur alumni. Years ago, someone from Dubai, now affluent and in his 60s, sent me a message: ‘Taherbhai ne malo to maaro salaam pahunchaavjo!’ (Please extend a salaam on my behalf when you meet him again).

Sadly, in one of those ironies, I once told Taherbhai so but he was unable to commensurately respond; the man who held thousands by the magic of his marsiya momentum was operated for a throat ailment and lost his voice forever.

A couple of days ago, Taherbhai and his stilled voice were lost forever as well. The voice may have been silenced and the man no more than an unrecorded memory, but somewhere when people recall Saifee Masjid in its glory days of the Seventies, they will remember the one man who packed more Bohras in a majlis than anyone before or since.