‘Paapar ne keh ki Chilli ne leg break naakhey; Salloo stump karse’ might sound gobbledygook to you but in the Calcutta Maidan of the Seventies and Eighties, this would be easily decoded by the Bohra teams.

‘Paapar’ was the nickname of the leggie with a ravenous paapar appetite. Chilli (Gujarati for a small bird) was opening batsman Saleh Shipchandler who lived on British Indian Street and possibly nibbled at his food often enough to earn himself an avian comparison; Salloo was wicket keeper Saleh Tyebbhoy who lived on Central Avenue and could be relied upon to move his gloves with speed.

A boy in the community was nicknamed ‘Paapar’ owing to his insatiable love for paapars! Shutterstock

In the Bohra community of Kolkata, one of the first things they did when you were old enough to walk to madrasa, was assign a nickname. You couldn’t just boringly be your formal name that most could not comprehend the meaning of anyway; there was another problem in that there were so many Mohammeds that one needed to tell them apart. Besides, you needed a nickname that was endearingly ‘you’ to the point that your original name became irrelevant in everyday engagement.

Endearment or abuse?

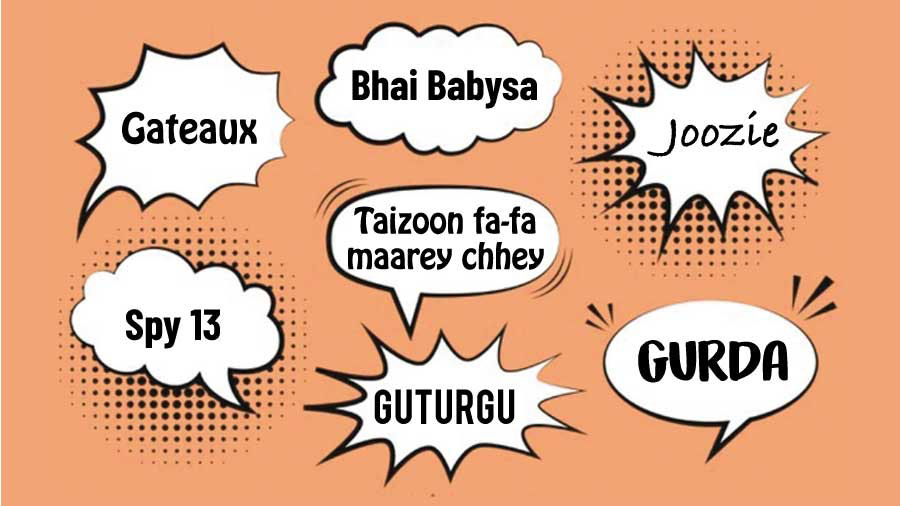

The formal name-derived nicknames were a no-brainer: Mustafa became Mustaf in the late Sixties when he was still in his shorts. He continues to be called that even though he has entered his 60s. Juzar became Joozie and since it might be awkward for a bearded mid-50s individual to be now so referred, the world has grudgingly turned to the way the name figures on his birth certificate.

The world has not been uniformly kind. For some reason, Abbas (who lived on Chandni Chowk Street above Haji’s) with the grand sounding surname of ‘Shipchandler’, continues to be universally referred to as ‘Gurda’ (kidney). I asked him; he said (unconvincingly) that it was because his father was large-hearted — like a kidney perhaps. What was relatively unkind was that the word by itself carried no positive attribute and did not sit musically on the tongue either, especially when you referred to him as ‘Gurdo! Saalo aayo ke nahin?’ and you can’t quite get whether it was said out of contempt or proximity. Besides, the nickname has endured across generations: his father Qayyum was ‘Gurda’, his mother Zarina automatically became ‘Gurda’ and now the Sydney-based Abbas continues to be ‘Gurda’. The parents left Abbas some money, diary (comprising birthdates of friends), family values — and an inherited nickname.

The custom within the Bohra community would be to turn a perfectly sounding nickname into a term of endearment by adding an ‘o’ at the end. Asgar Currimjee of Zakaria Street was generally ‘Lala’ to all, but suddenly converted into ‘Lalo’ after he had missed an open goal or dropped a sitter. The ‘o’ was an abuse by proxy when four-letter words were still not a part of everyday conversation.

The Nakhoda Masjid, which stands at the intersection of Zakaria Street and Rabindra Sarani Shutterstock

Verbs to nouns, and everything in between

Taizoon Dawoodi dithered critically in looping the ball to the wicket keeper from long stop, by which time the batsmen had run a third on the Red Road Maidan, so someone dissected his role down to a classic ‘Taizoon fa-fa maarey chhey’, which in our classic Surti meant he had lost his marbles. It would have been reasonable to expect that the chapter would have been closed by the evening post-mortem but somehow the recall of Taizoon fumbling with the ball between his legs had by now become a mental replay for all team members and their watching wives. Each time the name ‘Taizoon’ would be uttered, the word ‘fa’fa’ would be invoked in the same oxygen. The high priests of nicknaming felt that Taizoon had come of age; he had done enough to deserve a nickname; he had earned his gripes. The nickname ‘Fa-fa’ was polite; the green-eyed and urbane Taizoon became ‘Fa-fo.’ The verb had been noun-ed.

A name from Japan

The stories about how people got their nicknames were sometimes more interesting than the ‘what’. A young Faizullabhoy child was taken by his industrial family from Calcutta to Japan in the 1920s; the Japanese governess probably ran around the child periodically shrieking ‘Baby-san’ (literally translated into ‘Baby-sir’) to curb the child into submission. The household picked it up; it became the child’s nickname and then, more amazingly, his name. The child was referred to as ‘Babysa’ into adulthood. My father referred to him as ‘Bhai Babysa’ and in doing so, had dispensed with his first name and his surname. While writing this piece when I asked around for his first name (the one whispered into his ear by an aunt on the sixth day of his birth), people shrugged. When a kankotri (invitation card) was required to be sent for a shaadi nu jaman (wedding reception), the calligrapher arrived at his envelope and would be immobilised. How could he just write ‘Bhai Babysa’ on the envelope? He never knew if this urbane gentleman even had ‘another’ name. When his son Saifuddin went to pay his respects to the Syedna (spiritual guru) and mentioned his father’s formal name of Abdulhusain, the Syedna looked down for a moment, lost in thought. The son clarified ‘Mey Babysa no dikro (I am Babysa’s son).’ The Syedna suddenly arched back and is supposed to have replied, relieved: ‘Babysa! Em kaho ni! (Babysa! Why don’t you say that!)’

A Spy, a ‘Bhai’ and a woman called Gateaux

There was a player in the prominent Bohra maidan cricket team of Modern Cricket Club. He would turn up in whites; he seldom played; he was retained because he had a distinctive role. The whisper is that his official assignment was to snoop around opposing teams, pick the strategic drift (team composition etc.) and relay to his team to make last-minute changes. He was given a fitting nickname: since he was a snoop, the word ‘Spy’ fit him well; since he was never good enough to be 12th man, he was assigned the number ’13’. So Spy 13 he became. Even today when his picture is identified in sepia photographs, there is a pointed finger of ‘OMG! Spy 13!’ He should have been smuggled past Wagah for precious neighbourly details.

Maidan is a hotspot for impromptu cricket matches even today TT Archives

The Surtis were masters at name-fixing. Khadija became ‘Gateaux’ to the point that the entire Bohra community in Kolkata would refer to this old lady who lived on the first floor of 14 CR Avenue as ‘Buji Gatobai’ (‘Buji’ and ‘bai’ being terms of respect used by Surtis, quite like ‘Bibi’). Once when the postman turned up with a parcel in the name of Khadija Currim, the granddaughter is supposed to have replied ‘Yahaan koi Khadija nahi rehta!’

Abuli (this itself was a corruption of ‘Abdulhusain’) Motiwala was Abuli Lang-Lang to the world because he was a six-footer and ‘Lanky’ became ‘Lang’. Salehbhai became Jheena (small) because he barely tipped 5 ft and if he had studied law in England, his surname might have been corrupted to resemble the name of the man who founded a nation. Tyeb Motiwala became ‘Baldy’ to the point that the children of his cricket team would tentatively refer to him as ‘Uncle Baldy’ (only to be rebuked by the elders that ‘Saala, tamaara ma koi sharam chhey ke nahi!’). Another Tyeb (Sachee) was known as ‘Tyeb Toti’. A successful Bohra businessman continues to be referred to as ‘Shaikh No Problem’ after this term was used on more than one occasion in the Eighties. Bilquis Lanewala became ‘Billie (cat). Mohammed Khairulla was Minoo (and even worse, ‘Meena’ by the inner cicle). My grandfather Fidahusain became Achchoobhai in the nawabi tradition. Nobody remembers Tyebji’s actual surname, but because he was fair, the biting Surat of the Forties branded him ‘German’ and ‘German’ he remained even after he took the long train to Calcutta a decade later. New life he got; the old name he didn’t. The irony was that his entire personality was compromised when even ‘Tyebji’ was replaced with ‘Jimmy’. Out of respect for the jolly good soul he was, he would be, as a concession, referred to as ‘Bhai Jimmy.’

Jobs may come and jobs may go, but a nickname is forever

Sometimes the nature of one’s profession made the nicknaming process easy. Abbas Baxamusa handled the cash at the successful Bohra trading firm called CA Mohammed. After some time, his surname appeared so unwieldy that it was set aside for a simpler ‘Cashier.’ My mother referred to his wife as ‘Buji Banu Cashier’. The entire family had been renamed. Years later, CA Mohammed folded and Mr Baxamusa retired, but ‘Cashier’ stuck. You could get yourself a new life, new ration card and even new passport, but not a new nickname.

You couldn’t just boringly be your formal name that most could not comprehend the meaning of anyway… you needed a nickname that was endearingly ‘you’ to the point that your original name became irrelevant in everyday engagement

The one with the American, the ‘Chippu’ and the Duck

A venerable gentleman called Mohammedbhai on Chandni Chowk Street was referred to simply as ‘American’. Two brothers who generally bandied together everywhere they went were referred to as ‘Paaoli’ (two 25p coins). Most people struggle to get that the name of ‘Can Can’ Dahodwala of Taltala is Firoz. Faizullah Khairullah was referred to as Donald Duck. Shamoon Goga became ‘Laughing’ for obvious reasons; his wife Safya was nicknamed ‘Guturgu’ for not so obvious reasons. Yusuf Khairullah of Mission Row and Ripon Street remained ‘Baachcho’ for decades. Kaisar Bengali remained ‘Chippu’ into his 70s. A gentleman of Bhopali extraction would be referred to as ‘Bateyr’ (partridge) before he blurred out of existence.

This article does not touch another amusing aspect that would call for a completely different study — of Taher who lived near Elliott Road and was surnamed Vehmi (superstitious) or Murtaza who lived on Prinsep Street and was surnamed Vasi (Stale) or Fatema with lustrous hair who lived on Bentinck Street and became Gunja after marriage.

That’s another story for another time.