The ornate balustrade and dusty red steps leading up to Jayanti Das’s Park Circus apartment are relics of a bygone era. The high ceilings, window ventilators and the classic laal mati of the spacious rooms inside, are harbingers of the stories she’s about to narrate to me. She’s 94 years old but her vibrance suggests an elephantine memory of days long gone.

Jayanti Das née Seth was born on May 26, 1928 in a rambling old home in North Calcutta, near Minerva Theatre. It was a quintessential joint family where at least 30 people lived under the same roof. Her name wasn’t always Jayanti; it was Sita at the time of her birth, changed to Kamala later and only became Jayanti when she was ready to go to school. She remembers some of the happiest years of her life playing out in that house, even though she lost her mother to typhoid when she was only a three-month-old baby. Her formative years are marked by the memory of joyrides in a horse-and-carriage which her uncle, a homoeopath, would use for house calls, as well as simply being wrapped in the warmth of various aunts and uncles.

“My grandfather, Rajendranath Seth, was one of the first four to graduate with a Masters in English from Calcutta University. He went on to study law but gave it up because it involved having to lie too much,” she says, with a chuckle. Jayanti also remembers her grandmother as a fierce matriarch who was dead against her son (Jayanti’s uncle) marrying a Brahmo girl. It became the trigger for her father, uncle and widowed aunt to move to a smaller house in Maniktala when she was eight years old.

Jayanti Das sitting down to a lunch of dal-bhaat-lau-chingri, makes a quip about how simple home food can be found at high-end restaurants these days. 'Not that I go to expensive places. After I got married, my brother-in-law took us out to Trincas one night. I saw Usha Uthup then, she was a teenager. It was thrilling to be out on Park Street at night.'

While the first eight years of her life in the North Calcutta house, with its lavish meals of loochi in the morning and maachher jhol in the afternoon, might have been the happiest, the years to follow would be marked with adventure and excitement. Jayanti’s father, Phanindra Nath Seth, had been involved in the freedom struggle since the first partition of Bengal in 1905. He was a serious khadi-clad member of the Swadeshi movement and later became the secretary of the Indian Decimal Society (Bharatiya Dashamik Samiti) which was led by Hiralal Roy, a pioneering professor of engineering at Jadavpur University. Jayanti would come to know only when she was older that her father’s role as a freedom fighter and his subsequent imprisonment would lead other members of the family to ostracise them. In fact, his reputation would prevent her from gaining admission into Bethune Collegiate School (near Hedua) until class six, despite her father applying every year. “Being anti-government was not, in those days, a matter of pride,” she says, matter-of-factly. Years later, her father’s experience with building crude guns would come in handy during The Great Calcutta Killings of 1946, when their house was under attack and he was able to keep the mob away by shooting from the second-floor window.

Earthquake, famine and World War

Jayanti recalls the 1934 earthquake (which had devastating repercussions in Nepal and Bihar) causing a mere tremor when she was in school. When her desk wobbled and her handwriting turned into a scrawl, she picked a fight with the girl next to her, blaming her for deliberately upsetting the desk. Moments later the girls found themselves outside the schoolhouse as an earthquake alert was announced.

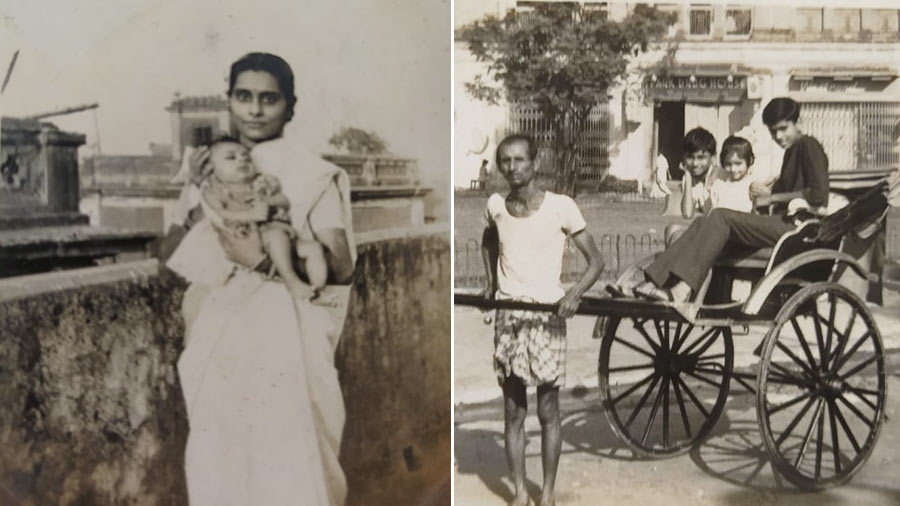

Jayanti on the terrace of her father’s house in Maniktala with her first-born and then later all three of her children (Subrata, Subir and Rini) in a hand-pulled rickshaw in Calcutta of the 1960s

In 1941, when Tagore’s demise was declared, the school stopped classes for the day and sent the girls home, but those who usually came by the school bus were left behind, much to their luck as it turned out. Tagore’s farewell procession passed right by the gates of Bethune and the pallbearers paused momentarily, allowing Jayanti and some others to lay their lotus flowers down at his feet. “That was the first time I saw Rabindranath. And of course, the last.”

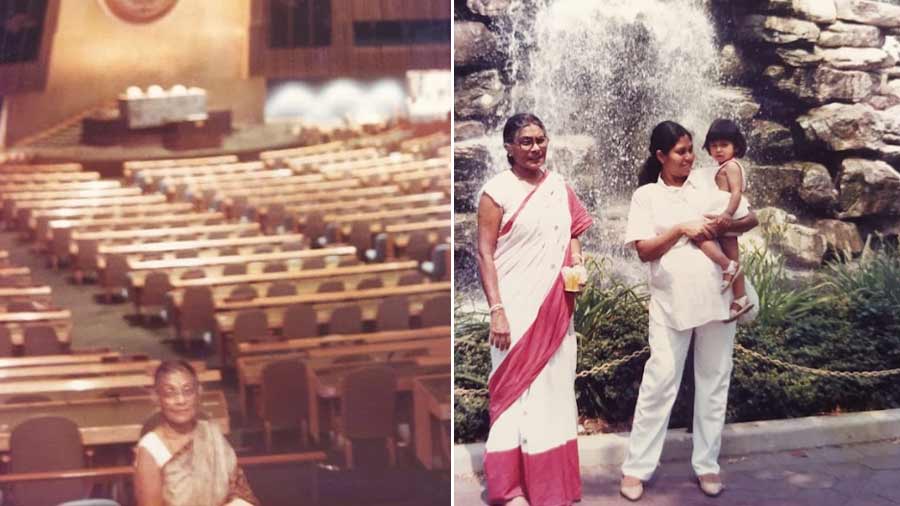

Jayanti took her first flight in the 1980s to see her daughter in America and then travel around the United States for a bit. She was most excited to visit the United Nations Headquarters (left) in New York

When the famine raged through Calcutta in the summer of 1943, Jayanti’s family, despite their desire to help those less fortunate, were unable to do much for the victims who trailed in from the outskirts. Phanindra Nath Seth, who was attempting to run a lozenge factory after his years in prison, found it difficult to make ends meet, and Jayanti watched the corpses pile up on the streets, as the hoarse pleas outside their gates went from begging for rice to begging for just the “phyan” (starch). “It was hard to hear,” she admitted.

Far harder than listening to the distant sounds of the city being bombed in the throes of the World War II, for while young Jayanti had empathy, she lacked fear. When the siren went off, Jayanti’s family huddled in the ground floor and the city plunged itself into darkness to be obscured from the view of Japanese fighter pilots. But Jayanti stole up to the terrace to see if she could see any bombs being dropped in the moonlight! In 1939, school was closed for a whole year, and in times reflective of the current pandemic, Jayanti stayed in to be home-schooled. She missed school greatly, with its basketball, tennis and badminton courts.

Chants of ‘yeh azadi jhootha hai’ punctured the cries of jubilation

The tumultuous years of the city’s history provided much fodder for excitement. Jayanti wasn’t prepared for the chaos of Direct Action Day (August 16, 1946) to last as long as it did, and was expecting to be back to college after things settled down. But schools and colleges closed doors for months, and the Lal Bagan bustee near her house rumbled with the stirrings of communal unrest. “The rioters did not attack the residential buildings, though they did set some shops in the marketplace on fire. My father told us to be prepared with boiling water and boiling oil if we ever needed it.”

While the Muslim League’s role in the Interim Government remained uncertain and the flames of communal violence flared over the following months, erstwhile freedom fighter Phanindra Nath Seth began to fortify himself with crude guns made with wood and pipes. He only had one occasion to fire and was given away when the British army arrived on the scene, with people pointing to their house saying “shots were fired from that Hindu house over there”. He quickly dismantled the pipes and hid the spare bullets, so when the armed police burst in, they found nothing. Less than a year later, at the stroke of Independence, he was invited by the local party to hoist a flag at the large water pump station. But the communists were upset that Independence had come to them at the cost of Partition, and their clamours of “Yeh azadi jhootha hai!” punctured the cries of jubilation.

Jayanti with her husband, Rana Das, and their children and grandchildren. 'It’s been years since all the children were together, but when they are, I’d like to make something special that day, like Chingri Cutlet or Koraishutir Kochuri,' says Jayanti

There was great resentment among the men that we were taking away their jobs

After graduating from Calcutta University, Jayanti found herself cast adrift in newly independent India, seeking a job and a husband, in no specific order. Being more resourceful about the former, she marched into the income tax officer’s cabin “with my friend who was Bipin Chandra Pal’s daughter” to demand a job. A startled commissioner of income tax informed the girls that they should apply immediately at the Employment Exchange. This is how Jayanti came to be employed as an upper division clerk at the Income Tax office, which was to be her workplace until she retired as senior supervisor. "I was one of the first women to be working at a central government office and there was great resentment among the men that we were taking away their jobs! My starting salary was Rs 150 per month," recalls Jayanti.

Rana Das and his wife Jayanti on their wedding day (left) and then on holiday, years later. The couple was proud of the communist ideologies they abided by. “When I was in school, the Hindu upper castes were becoming unbearable. Untouchability was on the rise on the outskirts of Calcutta, but we didn’t see it as much in the city. One thing I will grant the British is that they really did encourage education amongst everyone,” says Jayanti Das, now 94

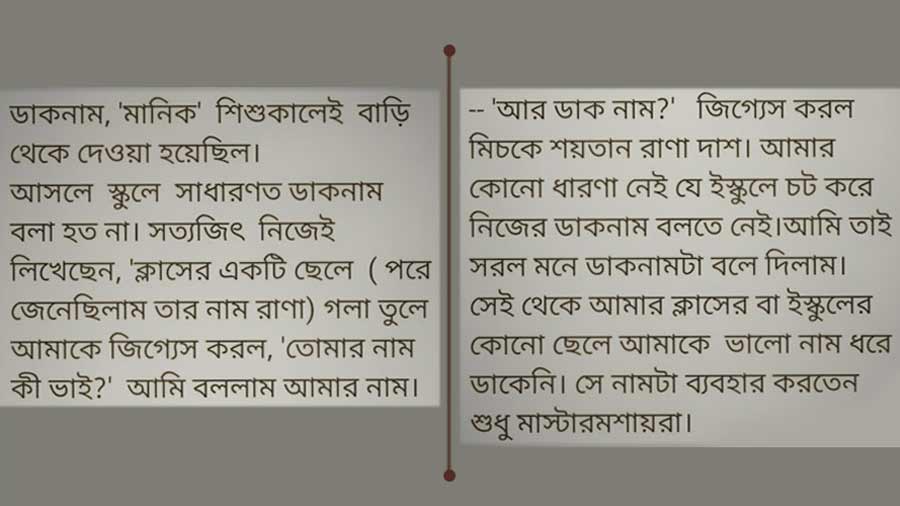

Her professional success was followed by some heartbreak when she was rejected by a suitor for not being fair-skinned enough and jilted by a boy she was sweet on. She wept for a couple of months before deciding that it was an utter waste of time to shed tears over a man and she cheered up just in time to be introduced to Rana Das, eight years her senior and an employee at General Insurance. He was also an active member of the local communist party, which was more interesting to her than the fact that he attended Ballygunge Government High School with Satyajit Ray, who was not yet famous. “Manik-da asked my husband if his company would want to fund his movie (Pather Panchali) and my husband told him in no uncertain terms that General Insurance would want to do no such thing!” she remembers, laughing now at destiny.

An excerpt from ‘Jakhan Chhoto Chhilam’ by Satyajit Ray tells us of the incident when his schoolmate, “michke shoytan Rana Das” got him to reveal his nickname, ‘Manik’, in class. One month after Ray passed away, Rana and Jayanti Das’s youngest grandson was born. His nickname is Topshe.

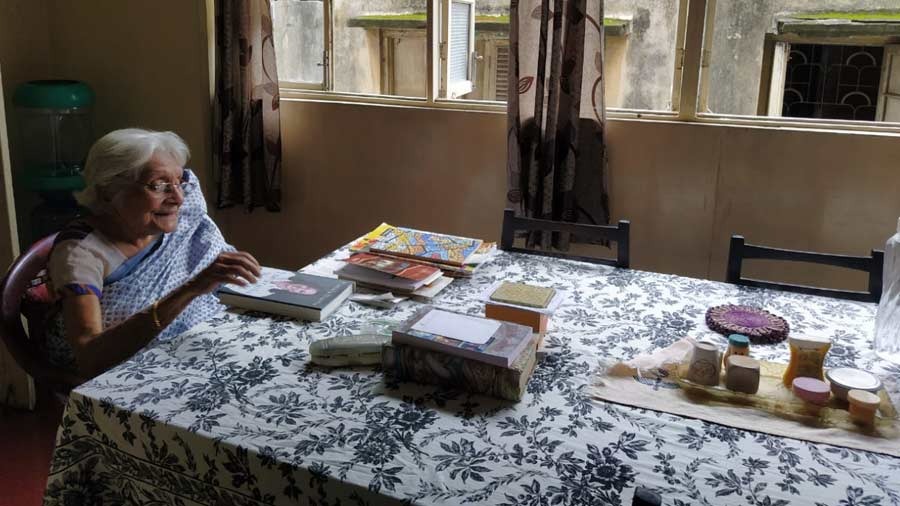

Rana Das and Jayanti Seth had a registry marriage in 1953. They hosted a tea party in the living room of the very house she’s now in. The wedding menu boasted aloo-kochuri, jilipi and cha, and there were more people than furniture. Seventy years, three children and three grandchildren later, the Circus Avenue house seems to have suddenly shed its inhabitants. Jayanti spends her days with books and many evenings at the Park Circus Institute, a club established by her husband in 1948. “My sons tell me I should live with them, but I love this neighbourhood… I can’t leave this house.”

I tell her then about my mother’s family who once resided in a house long demolished in Park Circus. She sits up even straighter than she already is. “The Khastgirs? My husband’s sister was married to your grandfather’s brother! I used to visit her all the time and I remember your great grandmother, the lady with the pearls and stories from Chittagong…”

It’s not every day that one stumbles upon a nonagenarian who can tell you a thing or two more about your own family. And we’re off again, twisting and turning down the annals of history…

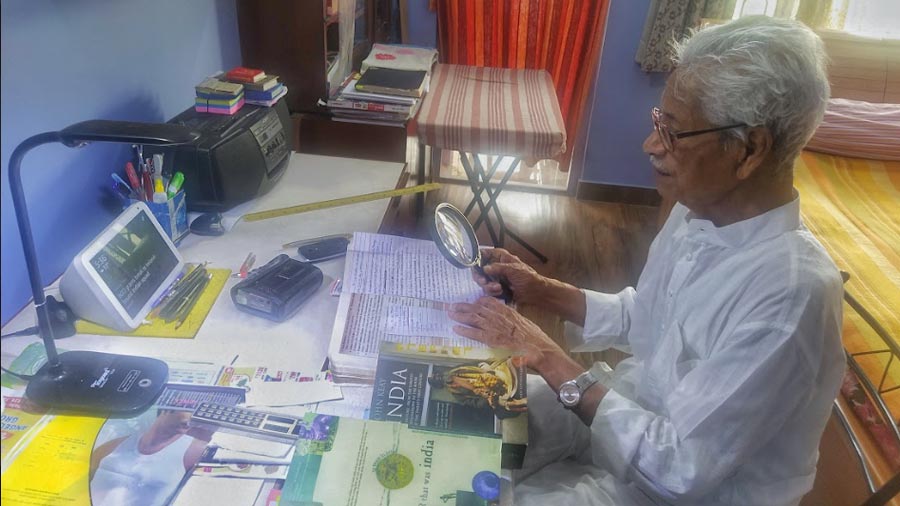

After a lifetime of reading Sarat Chandra, Bankim Chandra and Rabindranath, these days Jayanti likes to read travelogues and memoirs. She is currently reading ‘The Truths We Hold’ by Kamala Harris