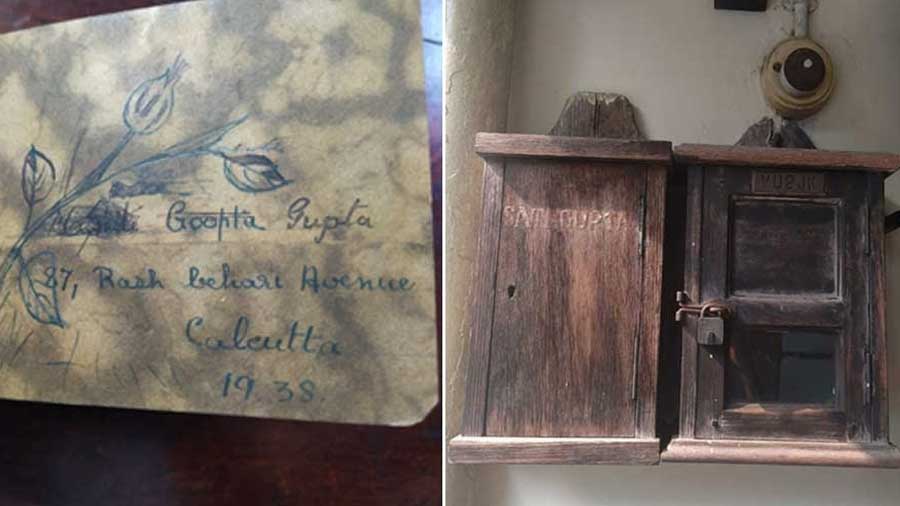

Born February 8, 1924, Sati Gupta née Gooptu is almost a hundred years old. Her great great grandfather Dwarka Nath Gooptu, the man known for having invented an antidote for malaria, had amassed wealth which led to sprawling properties across Calcutta. His great grandson, Amarendra, decided to move out of the family estate on Grey Street to a house he’d built on Rashbehari Avenue, and although the original idea was to move from there to a larger place closer to White Town (the Chowringhee to Dalhousie zone), they never did.

Sati Gupta is the grand matriarch of the two-storied manor house on Rashbehari Avenue, which she resides in with her two widowed sisters-in-law

Amarendra Gooptu’s daughter, Sati, with the many twists and turns of fate, grew to be the grand dame of the Gooptu Bari located at 87 Rashbehari Avenue. Hers has been a life of fortune and misfortune, but at 98 she’ll sit upright on her bed and greet you with a smile that lights up the long room flanked by two four-poster beds, and tell you how the road outside her house is unrecognisable to her these days.

100 rooms, 60 bathrooms and a doorbell ringing through the day

The Gooptu house on Grey Street

Five bigha or more, a hundred rooms, four courtyards, 60 bathrooms. This rambling old mansion on Grey Street (Aurobindo Sarani, connecting Ultadanga with Sovabazar) is where Amarendra Chandra Gooptu once lived with his family. His eldest child, Sati, remembers the armed guards and the doorbell ringing through the day. Her mother was only 10 when she moved into the estate as a tearful child bride, comforted by horse-and-carriage rides which inevitably ended with a new doll for her. But Amarendra moved out when Sati was five, embarking on a different sort of life, in a hitherto unpopulated part of Calcutta.

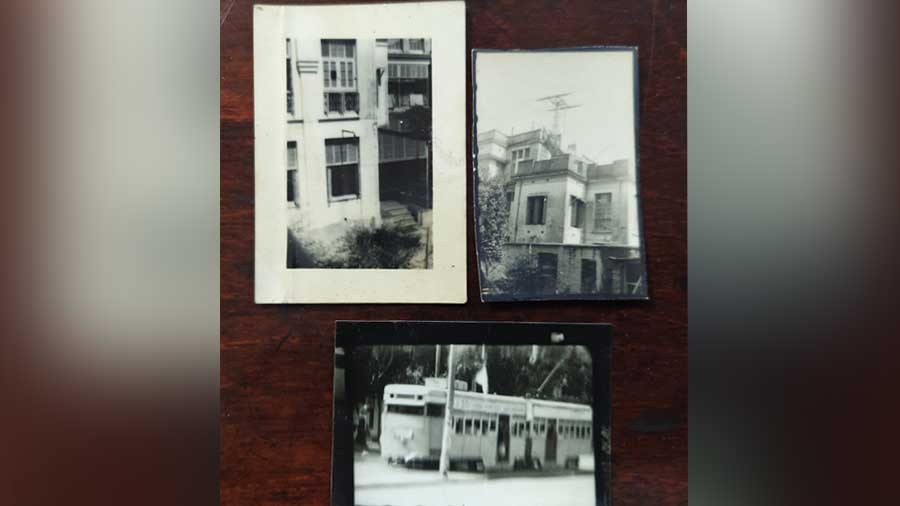

Amarendra Chandra Gooptu’s Rashbehari quarters. It is from this terrace that he played songs of victory on August 15, 1947. As the first Indian to own a ham radio in 1921, broadcasting was right up Amarendra’s alley

Plot 202 on Main Sewer Road, where tigers were heard!

The new house, listed as Plot 202 on Main Sewer Road, was far smaller than the Grey Street manor. Its modern address is 87 Rashbehari Avenue, one of the three Gooptu houses on this now-busy thoroughfare, all interconnected by their garden gates. But when Sati moved in, there wasn’t a soul in sight on these broad, deserted streets. Here, the foxes bayed outside and the roar of the tigers from Alipore Zoo – some 6km away – wafted down to her ears.

The garden gate that connects 87 Rashbehari to 85 Rashbehari Avenue

Old glimpses of the house on Main Sewer Road. Here, khichuri was made in a bathtub during the 1943 famine, to be handed out to starving peasants. ‘There were corpses strewn outside our gate every day, and voices pleaded ‘phyan dao phyan dao’ no matter how much rice we made,’ recalls Sati

Look! A bus, a bus!

The Dhakuria Lakes was in the process of being created and the tram line would soon be in the making. The rare sight of a bus trundling outside the gates would bring the inhabitants flocking into the courtyard when an informer would shout, “Look! A bus, a bus!”. They’d watch until it had rolled away, leaving behind the sound of ringing silence.

Sati Gooptu (extreme right) with her father Amarendra Chandra Gooptu, her mother Swarnalata, her sister Anjali and her brother Asoke (left)

Jewellery from Satramdas Dhalamal, cotton saris from Basanalay

Sati recalls being allowed to board a double decker bus as a special treat, where she watched the wide roads fly by her from the top deck. Trunks of jewellery from Satramdas Dhalamal, as well as boxes of Benarasi sarees would arrive at the doorstep for Sati and her sister, Anjali, to choose from, so that they might never have reason to repeat an item of clothing. “I wasn’t beautiful like my sister, you know. So my father would buy her the bright colours and give me the dull colours,” she reminisces. There was little reason for the girls to step out of home, other than to be escorted to school (Gokhale Memorial Girls' School) and back. Occasionally they would also buy cotton saris from Basanalaya opposite the house – a store on Rashbehari which still draws quite a crowd.

Himalayan black bear hankering for a midnight snack

Home was where the young ones in the family convened to play football on the grounds. Home was where deer cantered in the gardens and Pocket monkeys stole inkpots to toss at unsuspecting pedestrians. Home was also where a Himalayan black bear was growing into magnificence. Sati’s father had found the cub mewling on an Orissa-bound train and immediately purchased it for a rupee, proceeding to feed the creature a pound of bread and a bottle of milk. The memory of the cook starting awake in the middle of the night to find a grown bear sitting on him, possibly hankering for a midnight snack, still makes Sati giggle. The bear was gentle but he started to become too large for life on Rashbehari and eventually had to be given up to the Alipore Zoo.

A trough for the birds that has stood the test of time. Sati is still known to call down from the second floor asking about the birds that come a-visiting. There are some regular callers!

Back to her father’s house

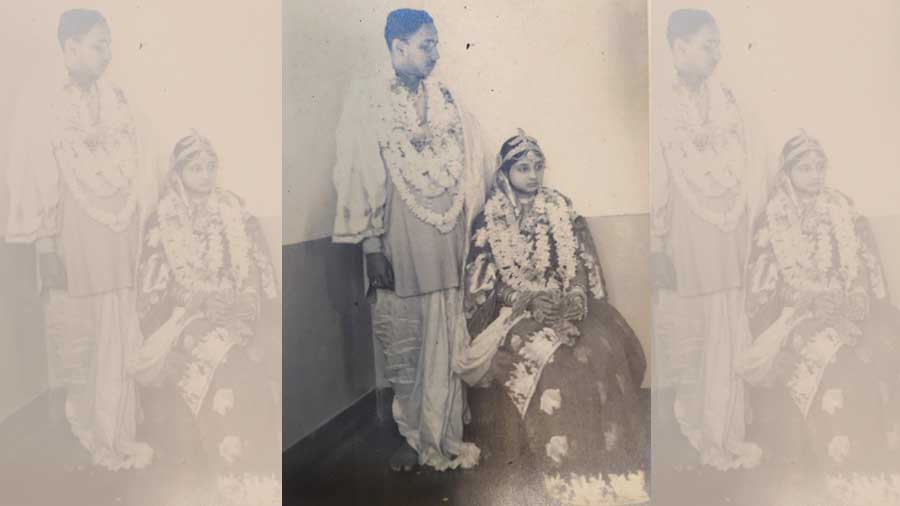

Sati on her wedding day, with husband Ajit Kumar Gupta

Sati’s brief absence from Rashbehari only occurred when she left as Ajit Kumar Gupta’s wife in 1941. When she was widowed a few years later, at the age of 26, after the birth of her daughter Eva, she moved back to her father’s house on Rashbehari. As a widow in the 1950s, life changed irrevocably for Sati; there would never be any going back to the days of her youth again. She donned a white sari and cooked her own food in separate utensils. Years later, after Eva had grown up and fled the roost, Sati began to take charge of the property her father had left behind for her. But the practice of preparing her meals and eating in isolation only stopped when she went to America to visit her daughter in 1964.

Koraishutir Kochuri – entirely ‘phulko’ and green

Eva remembers how mealtimes were elaborate affairs in this staid, old house on Rashbehari. Growing up in the 50s, she recalls the kitchen duties being very segregated, with her mother Sati looking after the vegetables, her aunt Anjali making the meat or fish and her grandmother being involved in the special mishti of the day. Sati, regretful of having to give up her sweet tooth now, remembers her mother’s milk-based desserts fondly, the memory of the Lobongo Lotika still lingering on her tongue. Sati herself was a formidable cook and until recently, could whip up Koraishutir Kochuri hitherto unparalleled in the family. “It should be entirely phulko and green. The secret is in the making and the rolling of the dough,” she says, her eyes twinkling.

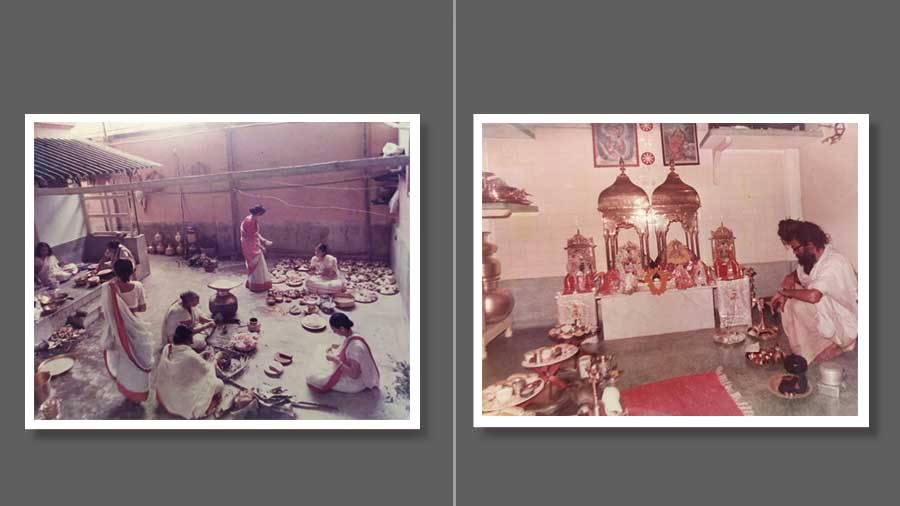

Durga Puja with a difference

The women of the house prepare for Durga Puja rituals which are more than 300 years old. In this avatar of Durga, she is not accompanied by Lakshmi and Saraswati because, as Eva puts it, “The story of Durga coming home with her children was created by the zamindars less than 300 years ago.” In fact, the Durga Puja in Sati’s house coincides with a Vaishnav Narayan Puja, with Narayan on a throne alongside Durga.

A touch of Tagore

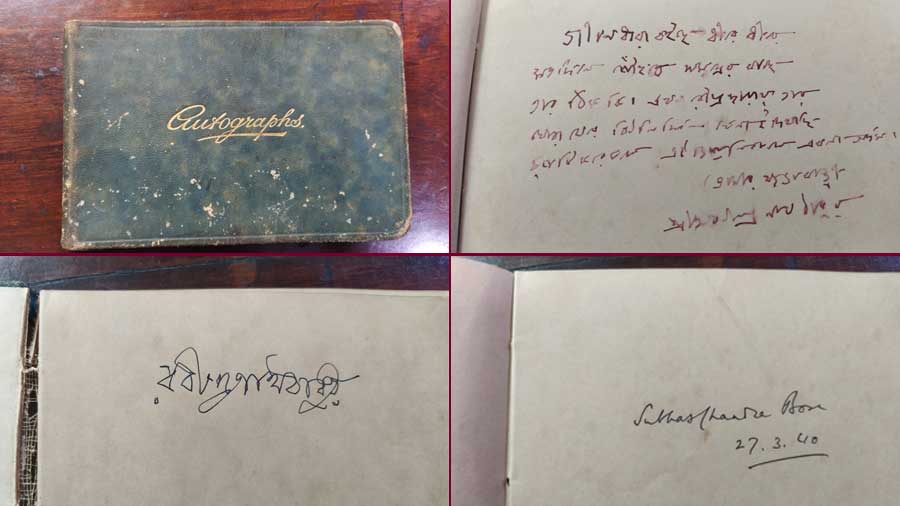

Sati owns a small diary which contains the inscriptions of many an eminent personality. A poem by Abanindranath Tagore and an autograph by Subhas Chandra Bose are pencilled into these yellowing pages. But it is Rabindranath Tagore’s signature she is most attached to, having chanced upon the poet visiting Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis in the Gooptu garden house of Baranagar which the scientist was renting. Tagore would often stop there on his way back from Santiniketan and it is here that his young fan cornered him with her autograph book. Years later, she rushed to meet Subhas Chandra Bose when news came to them that he had dropped in at a bank off Rashbehari. Sati immediately took her autograph book and had the darwan escort her to the bank to meet Netaji.

Hing Begun Bori to 'Rani Rashmoni'

Sati Gupta with her nieces and her daughter Eva Ray (standing, right) in the Rashbehari house

These days, Sati’s movements are restricted but she is just as involved in the daily mechanisms of her estate as she always was. There are few decisions that her daughter and nieces take without her approval. The details of mealtimes are still important to her and her mornings begin by surveying all the vegetables which have been bought and deciding on the menu. It is often a 10-course meal comprising various vegetables. From Hing Begun Bori to Kumro Flower fritters, the variety can be astounding. She’ll even oversee the hing which is being measured out for the recipe and insist that the potatoes for the different curries be chopped in different ways.

In the evening, Dal Puri or Kochuri-Aloo might be sent out to her nieces who live in other parts of the city, who she will call for updates every other day. Sati keeps the help on their toes by her constant queries about whether the main gate is closed, which tree is flowering and whether the antique furniture has been polished. It’s hard to pull a fast one on this soft-but-sharp grand dame who unwinds at night by watching programmes on DD Bharati or the latest episode of Rani Rashmoni.

Centre of adda and cynosure of warmth

“My mother was dealt a difficult hand but she has always been engaged with life,” explains Eva. “87 Rashbehari was where all the adda happened, where everyone convened every evening. She was the cynosure of warmth when I was growing up.”

And half a century later, that’s exactly what she still is.

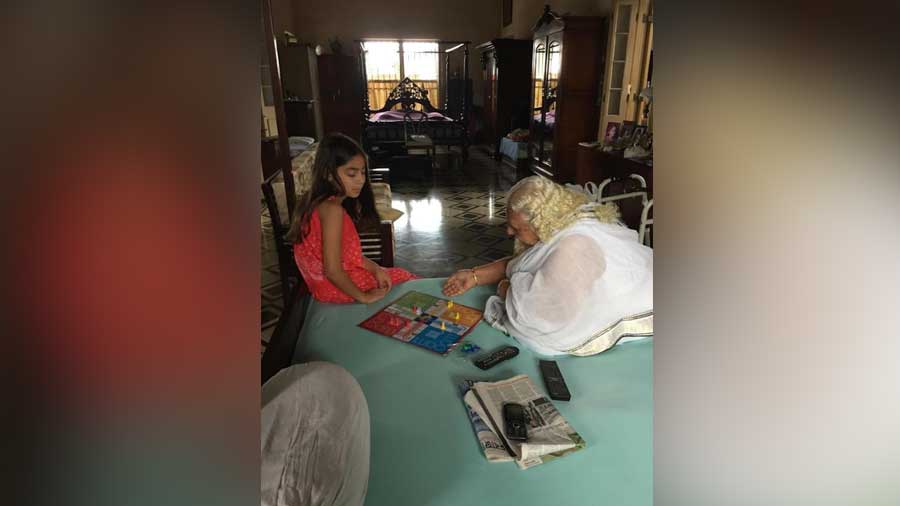

Sati Gupta playing Ludo with her great granddaughter, Juliana Ghosh, in her room at 87 Rashbehari Avenue

Read more in this series here