On July 29, 1946, a young man made waves when he sang Dheu utchhe, kara tutchhe in support of a strike called by postal department employees. Around the same time, he wrote and composed another protest song — Bicharpati, tomar bichar korbe jara.

Salil Chowdhury was born (1925) in an era when poets, writers, artists, thinkers, theatre activists and any creative personalities were known to raise their voice against political aggression. From the middle to the end of the 1930s, Europe witnessed an ugly period of political unrest, which included suppression of the voice of democracy and humanity in Spain, Italy and, finally, in Germany.

It was a time when intellectuals, many of them influenced by Communist ideology, came forward in support of a civilised world.

In India, Rabindranath Tagore, then in the last stages of his life, became vocal against such draconian laws.

Chowdhury moved to Calcutta from Assam in the early-1940s. His childhood in Assam had been enriched by both folk and Western classical music at home.

Between 1941 and 1942, became a member of the Communist Party of India’s students’ wing in college and slowly started mingling with various cultural activities of the union, playing the flute, an instrument he had mastered from his childhood.

Having committed a series of political blunders, the CPI was then gradually losing its connect with the masses. Its decisions like openly supporting the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan, abusing Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in the most obnoxious way, avowing the World War II as a “people’s war” as soon Russia was attacked by Germany and many suspicious instances of hobnobbing with the British government practically dented its public image.

At that point of time, Puran Chand Joshi, the all-India general secretary of CPI, played a masterstroke. In 1943, Joshi, in the backdrop of war and famine in Bengal, opened a cultural front of CPI by the name of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) in Bombay with some extraordinary young talented cultural activists such as Ismat Chughtai, Shailendra, Balraj Sahni, Ravi Shankar, Zohra Sehgal, Timir Baran, Chetan Anand and many more.

IPTA created waves in India, particularly in Maharashtra, Bengal, Assam, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh, with its exceptional rendering of songs, theatre, street plays, poetry, paintings, literary works and even cinema and dance.

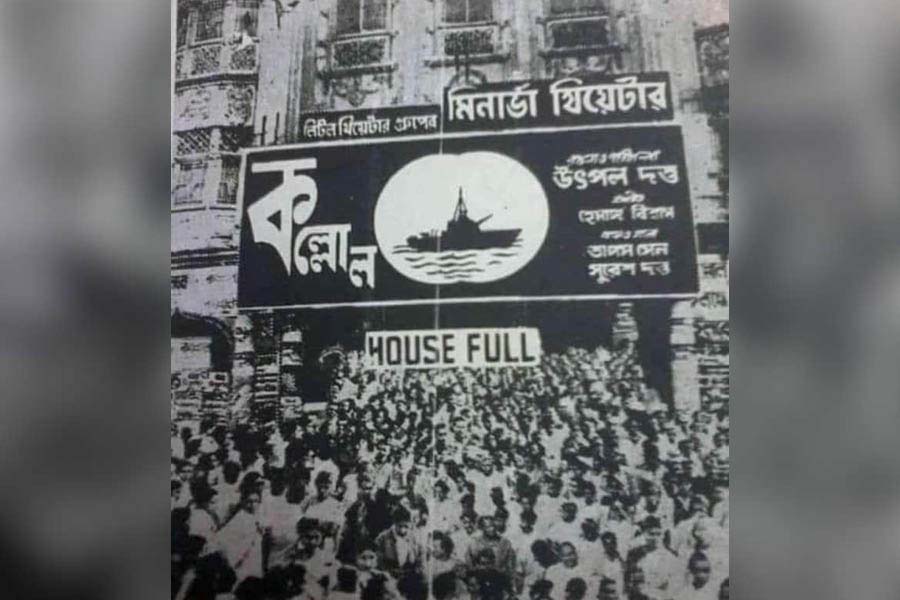

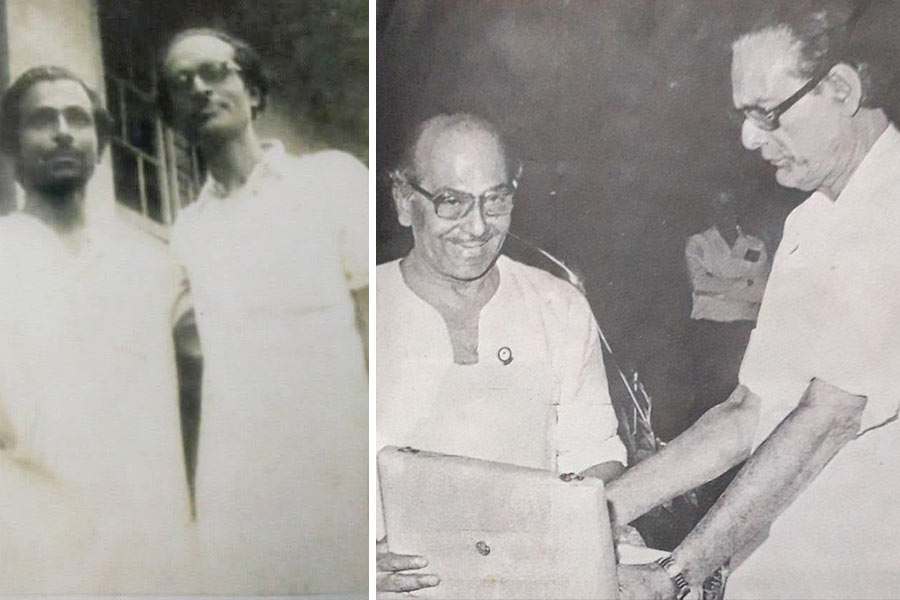

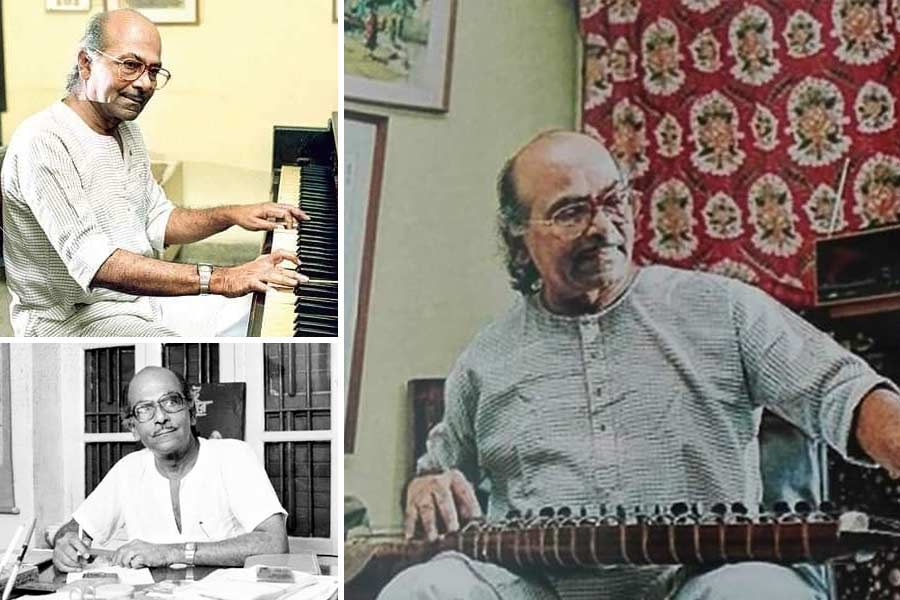

Salil Chowdhury (left) and Hemanga Biswas locked horns in open session of IPTA’s national conference in Bombay in 1953, while (right) his decades-long association with Hemanta Mukherjee could be considered a blessing to generations of music lovers)

From 1945, Chowdhury joined IPTA’s Bengal front and started working closely in Calcutta and the 24-Parganas. He was already an active member of the CPI students’ front and had the opportunity to perform at the Bengal Provincial Students’ Federation conference held in Khulna in 1942 as a young flute player. He was then yet to write or compose gana sangeet (song of the masses) at an open forum.

As the popularity of IPTA spread across Bengal from 1943, Chowdhury came in the limelight with his lyrics and compositions, which were a blend of western tunes played on eastern musical instruments. His compositions gradually became the main attraction of any IPTA show. By 1945, Chowdhury had become a known name among Communist workers across Bengal and Assam although other popular gana sangeet singers and musicians of IPTA such as Jyotirindra Moitra, Hemanga Biswas, Debabrata Biswas and Hemanta Mukherjee were also emerging fast.

Between 1947 and 1958, Chowdhury set to tune three famous poems of Sukanta Bhattacharjee, a Left-leaning young poet who died before he turned 21. These cult songs were Runner, Abak Prithibi and Thikana. All three were recorded by Hemanta Mukherjee in the 1950s, while the first one was rerecorded in 1988 by Lata Mangeshkar.

Chowdhury mingled with the peasants and toured the famine-ravaged villages of Bengal, witnessing the unimaginable sufferings of people since 1943. He was also writing short stories and street plays apart from songs. It was the time when he conceived the idea of writing a short story named Rickshawwala and a long poem Kono Ek Gnayer Bodhu.

The story was later turned into a film and the poem was tuned into an eternal song. Sadly, both these ground-breaking creative expressions made him a subject of strong criticism from party comrades.

Chowdhury started editing a Left-leaning Bengali cultural magazine Gana Natya from 1952-53. In this magazine, he published the complete musical notes of his long poem Gnayer Bodhu, which he set to tune. The song was recorded by a young Hemanta Mukherjee in 1949 and became a runaway hit, smashing all records of modern Bengali songs and fetching huge commercial success for both The Gramophone Company and Chowdhury himself.

It was the time when knives were slowly coming out against Chowdhury within his own party. After P.C. Joshi was removed from the CPI top office, B.T. Randive took over. A brilliant student from the University of Bombay, Randive had little understanding of the utility of IPTA. He, unlike Joshi, did not encourage the growth of the party’s cultural front and rather allowed an unjustified cultural policing by planting some cunning party members to check the merit of IPTA members’ creative outputs.

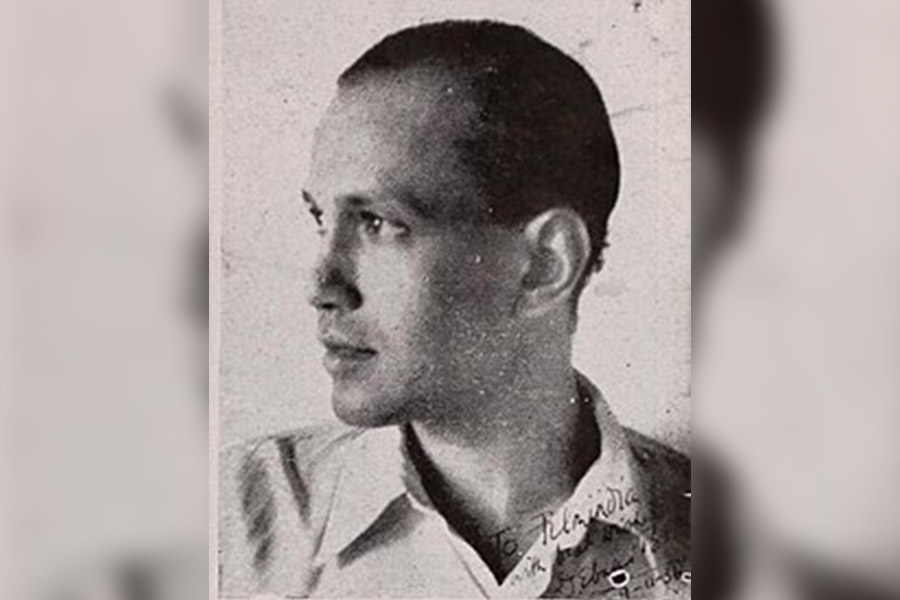

A young Salil (on harmonium) leads an ensemble with Lata Mangeshkar on the vocals

According to noted scholar and researcher of the Left movement in India, Basu Acharia, these people, with no taste of culture and no knowledge of art, started disturbing many talented IPTA members. If Ritwik Ghatak is the most famous victim of this horrific cultural policing within the Communist party, Chowdhury was a silent victim of the same.

Inside his own party, Chowdhury was unofficially attacked for the lyrics and music of Gnayer Badhu. He was questioned why a Communist would write a song describing the blessing of goddess Lakshmi behind a bumper crop and the use of conch shells, a ritual practised by Hindus.

Chowdhury soon found himself under a similar attack for another of his compositions, Aaye brishti jhepe. Here, he was asked how as a Communist he could believe in bidhata or fortune. Personal envy and blind political faith grew as Chowdhury started working in Bombay’s Hindi cinema and his work started captivating all of India.

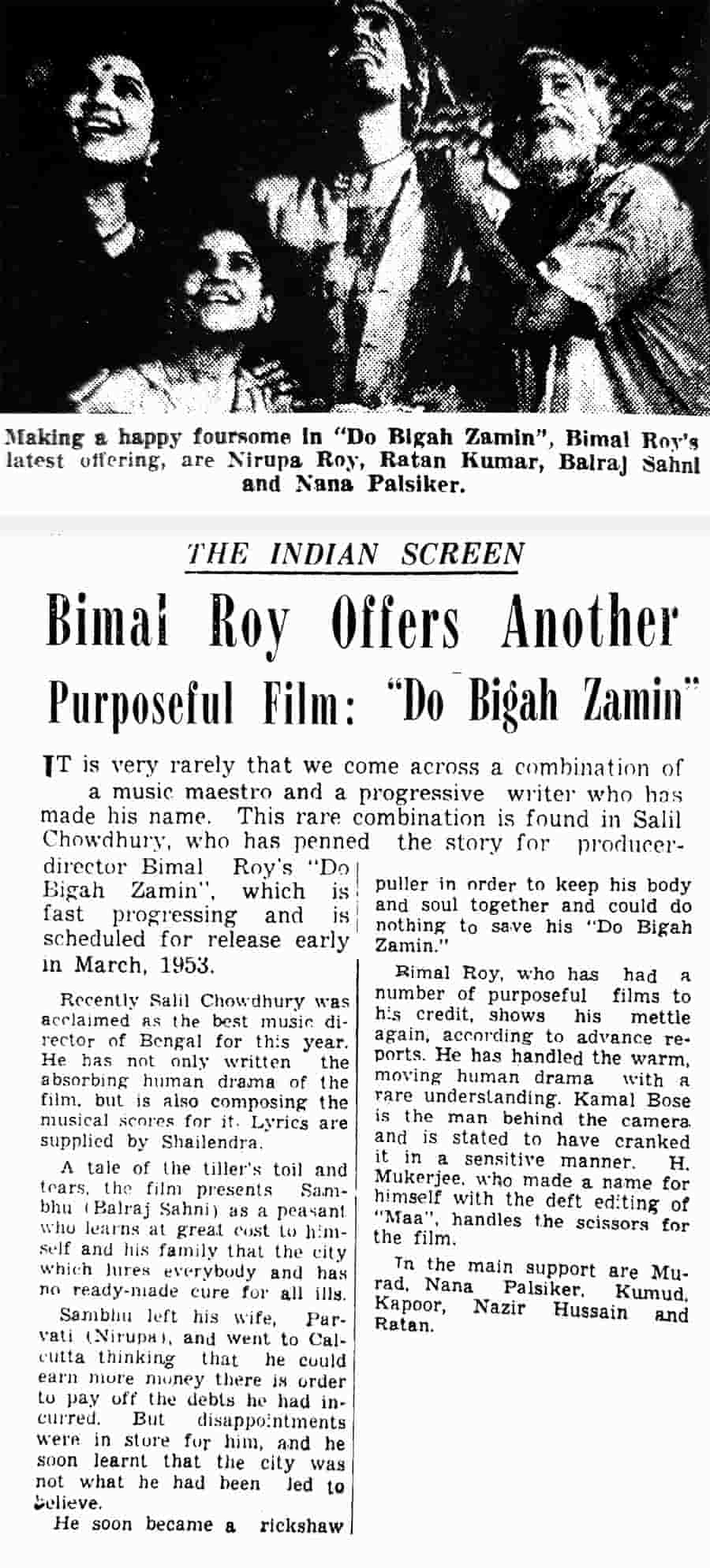

Though Chowdhury started working as a music director in Bengali films from 1949 and scored the music for at least three movies Paribartan (1949), Borjatri (1951) and Paasher Bari (1952), he delivered his first magnum opus in 1953 while working in Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin. This cult Hindi movie was based on Chowdhury’s short story, Rickshawwala, narrating the painful saga of the migration of a poverty-stricken farmer to a big city to work as a daily wager. Chowdhury scored the music of the movie as well. It became such a masterpiece that on December 21, 1952, The Times of India in its weekly cine review wrote “It is very rarely that we come across a combination of a music maestro and a progressive writer who has made his name. The rare combination is found in Salil Chowdhury, who has penned the story for the producer-director Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin.

The article on ‘Do Bigha Zamin’ in The Times of India dated December 21, 1952

The movie rocked the box office and also drew huge appreciation at various film festivals across the globe. Along with Raj Kapoor’s Awara, Do Bigha Zamin also gained so much popularity in Russia that soon Chowdhury was invited to visit various cities of Russia with Bimal Roy, Nargis, Nirupa Roy, Raj Kapoor, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Durga Khote, Balraj Sahni and Dev Anand.

From 1953 to 1958, Chowdhury started travelling to Bombay off and on to score music for one after another iconic Hindi movies like Naukri, Madhumati, Biraj Bahu and Jaagte Raho. From 1958, he settled in Bombay and stayed there till 1980, engaging himself nearly full-time as a music composer of Hindi films. Chowdhury’s involvement with commercial Hindi movies did not go down well with many of his party co-workers in Calcutta.

In 1953, IPTA held an annual cultural conference at Bombay’s Shivaji Park near Dadar. Chowdhury was by then embroiled in such a quagmire of dirty politics that his name was not even included in the list of delegates though he was the most popular IPTA member from Bengal.

By the time Chowdhury’s name was included and he arrived in Bombay to take part in the conference, he was castigated in the open forum at Shivaji Park by others for his use of western tunes.

It was even said that Chowdhury’s songs, which had Russian influences, sounded more like modern songs than ‘gana sangeet’

Hemanga Biswas, representing IPTA of Assam, accused Chowdhury of not reaching the common masses through his music because of his use of foreign tunes. Biswas said the song written by Chowdhury for a boatman or a farmer was not understandable to any boatman or farmer of this country. It was even said that Chowdhury’s songs, which had Russian influences, sounded more like modern songs than gana sangeet. Many people questioned his change of orchestra arrangement in recorded versions of his composition.

Chowdhury was by then very much aware of the power of his own talent and ignored the allegations but he was broken within. He realised that his dedication towards his political ideology was bound to have a conflict with his musical potential. As he was at the pinnacle of his career at that time in Bombay, Chowdhury decided to stay back and maintain cursory touch with IPTA as done earlier by Ravi Shankar, Raj Kapoor, Shailendra, Chetan Anand, Kaifi Azmi, Khwaja Abbas Ahmed, Hemant Kumar and other.

Chowdhury, who once teamed up with Shailendra, to create the legendary IPTA song Tu zinda hain tu zindagi ki jeet mein yakeen kar, also teamed up with him again in many commercial Hindi films. One of the finest of these two IPTA members’ work is RK Films’ film Jaagte Raho (1956). The film was also made in Bengali in the same year by the name Ek Din Ratre, directed by two IPTA members Shambhu Mitra and Amit Moitra.

Chowdhury’s active years with IPTA producing matchless politically motivated gana sangeet can be divided into two parts as written by Kankan Bhattacharjee. The first is from 1945 to 1953 till the time he did not taste the success of Hindi movies and another is 1953 to 1958 when he was based in Bombay and doing the same job from there. After the division of CPI in 1964, the golden days of IPTA were nearly over and Chowdhury had barely had any relation with the organisation. However, he wrote and composed a few gana sangeet for IPTA after 1980.

Chowdhury belonged to a generation that had seen the horrors of Partition, communal riots, war and famine. So, for them, poetry and music were much more than amusement and rather the best weapon to establish a classless society.