More than half a century ago, as the city prepared to bid farewell to one of the most tumultuous years in its history, a grisly incident inside one of the city’s most prestigious educational institutions sent shockwaves through the community, and even today, persists as a dark blot in Kolkata’s history. We look back.

The year 1970 saw the waves in the wake of Chairman Mao’s ‘Spring Thunder’ rock the city’s boat well and proper. The year had started with a mob crashing through the gates of the Royal Calcutta Turf Club and setting fire to the stands, weighing rooms, restaurants and office areas. The wife of the West German consul was hurt in the ensuing melee, while the wife of the British High Commissioner had her necklace torn off her neck by one from the mob. A worse fate befell the wife of the French Consul, who was hacked to death in her sleep, the consul escaping with grave injuries.

Total failure of law and order

On the political front, the state lurched from precarious balance to complete instability with the governor suspending the Assembly on March 17 due to total failure of law and order. That afternoon, convoy after convoy of armed forces rolled down the streets. President’s Rule was announced two days later. The sites of learning were not spared either.

On March 2, students of Presidency College ransacked the room of the principal, and decorated the wall with slogans and stenciled portraits of Mao. Incidentally, one can catch the Maoist slogan-marred walls of examination halls in the final entry of Ray’s Calcutta Trilogy: Jana Aranya. By the end of the month, student demonstrations became a regular feature at both Calcutta University and Jadavpur University. It came to a major boil on April 10, when pro-Naxal students of Jadavpur University invaded Gandhi Bhavan, an auditorium on the campus, pulled down and destroyed a life-size portrait of Gandhi, made a bonfire of a large number of books written by him, as well as books written on him in the library. They also burnt the Gandhi Study Center at the University.

The reconstructed Gandhi Bhavan auditorium in Jadavpur University Wikimedia Commons

As a consequence, prof. Hemchandra Guha, the vice-chancellor of JU, resigned, taking moral responsibility. Clashes between members of the SFI, the students’ wing of the CPI(M), and students swearing loyalty to Naxalism, spiraled out of control with the use of small country-made bombs (locally known as ‘peto’) becoming a regular feature. April 29 saw a SFI member brutally assaulted, leading to the university closing the next day. That very night, a pharma student, known to be Naxal sympathiser, was murdered in the mess dining hall – with the finger of suspicion pointing at SFI elements. This is how it went on for much of the rest of the year.

A quiet man, but with fortitude

On August 1, 1970, Gopal Chandra Sen, a professor of the mechanical engineering department, was appointed as the acting vice-chancellor. Sen had once been an engineering student at JU, and as a young man had been a satyagrahi, taking part in the Satyagraha Movement. Years had passed, but Gopal Sen remained a Gandhian at heart – a quiet man, but with fortitude. Under his watch, the examinations of the engineering department were conducted in September. In November, when four young students, one of whom was from JU, were gunned down in cold blood by the police, Gopal Sen was the lone dissenting voice from the education sector – criticising the use of violence on students in strong words. He received death threats, but refused police security – firmly believing and voicing that no matter what, his students can never harm him.

By the side of a pond that was located near JU’s Central Library, five assailants, armed with iron rods, sticks and knives jumped Sen Jadavpur University

December 30, 1970, was the last day of Gopal Sen’s tenure as vice chancellor. He was supposed to return to his regular duties at the mechanical engineering department the next day. At the end of the day, Sen handed over the responsibilities to the university registrar, politely refused the latter’s offer of a lift, and set out for his usual walk to his quarters within the campus. By the side of a pond that was located near the Central Library, five assailants, armed with iron rods, sticks and knives jumped Sen. As the blows rained down, Sen, who had been stabbed at 10 different places, collapsed, bleeding profusely, barely yards from his residence. A watchman first spotted the sickening scene and his shouts alerted the campus, the assailants having fled by jumping the boundary wall. Sen was rushed in a taxi to the hospital, but was declared brought dead. The next day, when he was supposed to rejoin the mechanical engineering department, Gopal Sen’s mortal remains were taken to the Keoratala burning ghat for cremation, accompanied by a long procession of students and colleagues. A genial and caring man, who had signed examination pass certificates at his residence due to intervening Durga Puja holidays, Sen’s brutal murder had everyone stumped.

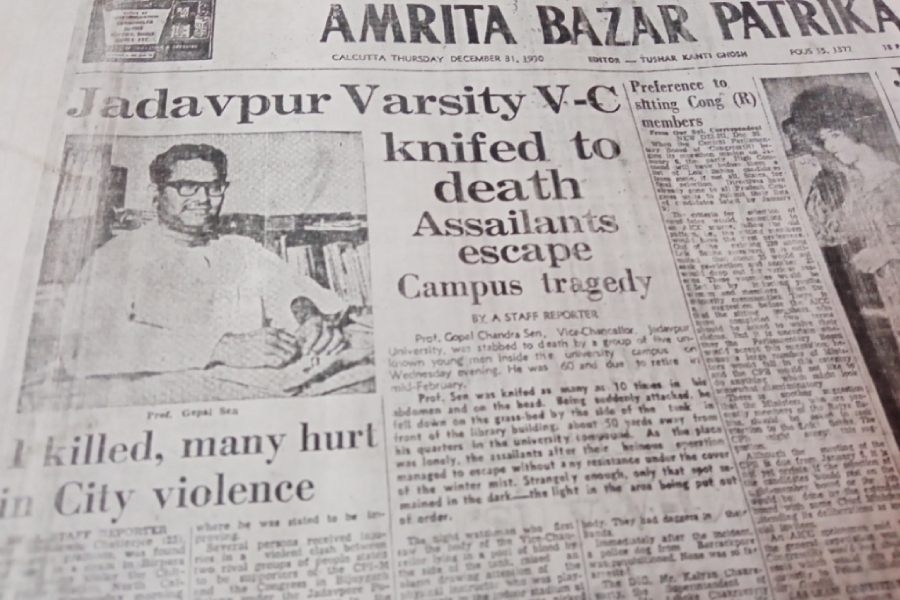

A report in Amrita Bazar Patrika, on December 31, 1970 Trinanjan Chakraborty

The first day of 1971 broke with the news of the arrest of Rana Bose, a chemical engineering student of JU, and Prabhat Barik, a local resident who was a driver by profession. Bose, the son of a well-known doctor, was known to be an active Naxalite. He was imprisoned for well over a year, during which time he was subjected to brutal police torture that left him unable to even walk at one point of time. He was eventually released in late 1971, thanks to the intervention of Bhupesh Gupta, a CPI MP who was a friend of the family. With a gruesome shadow hanging over his head, Bose was unable to secure admissions anywhere in India and eventually migrated to the USA. Another key suspect was Abhijit Das, a prominent Naxalite, formerly a JU student, who had been underground at the time, organising activities in districts. Police believed Das to be the brain behind the heinous crime and launched a major manhunt, but couldn’t apprehend him.

Gopal Chandra Sen’s murder mystery remains unsolved to this day. A mild-mannered academician, who firmly believed in the Gandhian approach till his last moment and was generally liked by all students, became one of many casualties in those turbulent times.