For centuries, in Bengali Brahmin households, the poite has been the sign of a boy setting out on the Brahmanical path to manhood. Last month, a probashi couple based in Seattle decided to examine it beyond gender and caste.

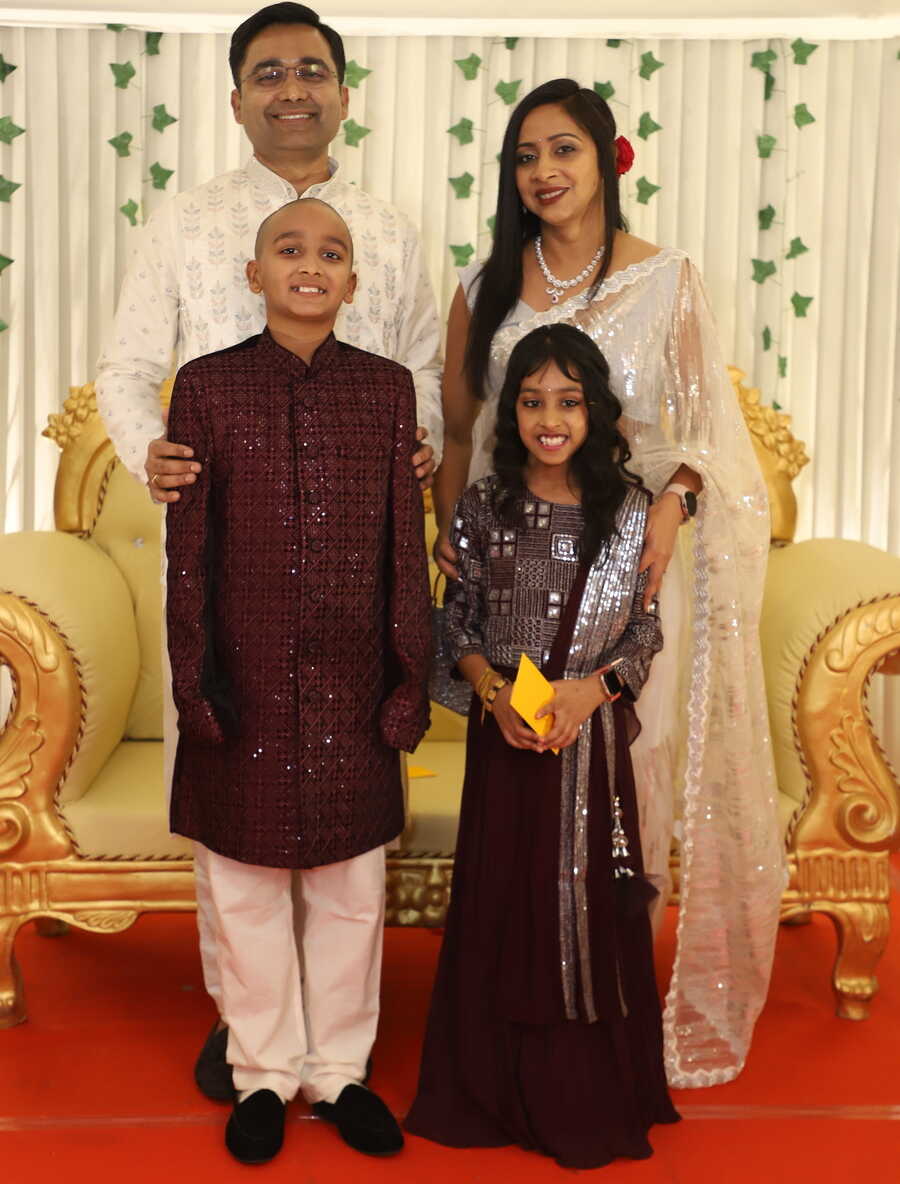

Ananda and Sohini Bandyopadhyay, who work for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, have always prioritised equality and sought logic while bringing up their two children, Hrid and Heeya. While Ananda is the deputy director of the foundation’s Polio team, Sohini works in the field of gender equality. Naturally, the couple were faced with a unique conundrum when Ananda’s father insisted that they organise a poite or upanayan (sacred thread) ceremony for their son.

“For months, Sohini and I had a prolonged discussion about the need for this custom in the modern world, especially with its implications of caste and gender,” said Ananda, speaking to My Kolkata on a family visit home to Kolkata this winter.“At our home, we take extra care to treat both our son, Hrid, and daughter, Heeya, equally. We have always had them both tie rakhi and give phonta to each other,” added Sohini.

Traditions and modernisation

From the start, the couple were clear that this couldn’t just be another religious ceremony. For Ananda, his poite was a distinct childhood memory — an event that had brought the family together. However, he was also skeptical of glorifying a discriminatory practice. While Sohini’s family had never had a similar ceremony, she felt that it was important to continue it as a family tradition. “I felt that modernisation and westernisation aren’t the same, and there is a way to adapt the custom to today’s world. That’s how our relationship is — Ananda questions traditions, while I come up with answers to contextualise them!” she said, chuckling.

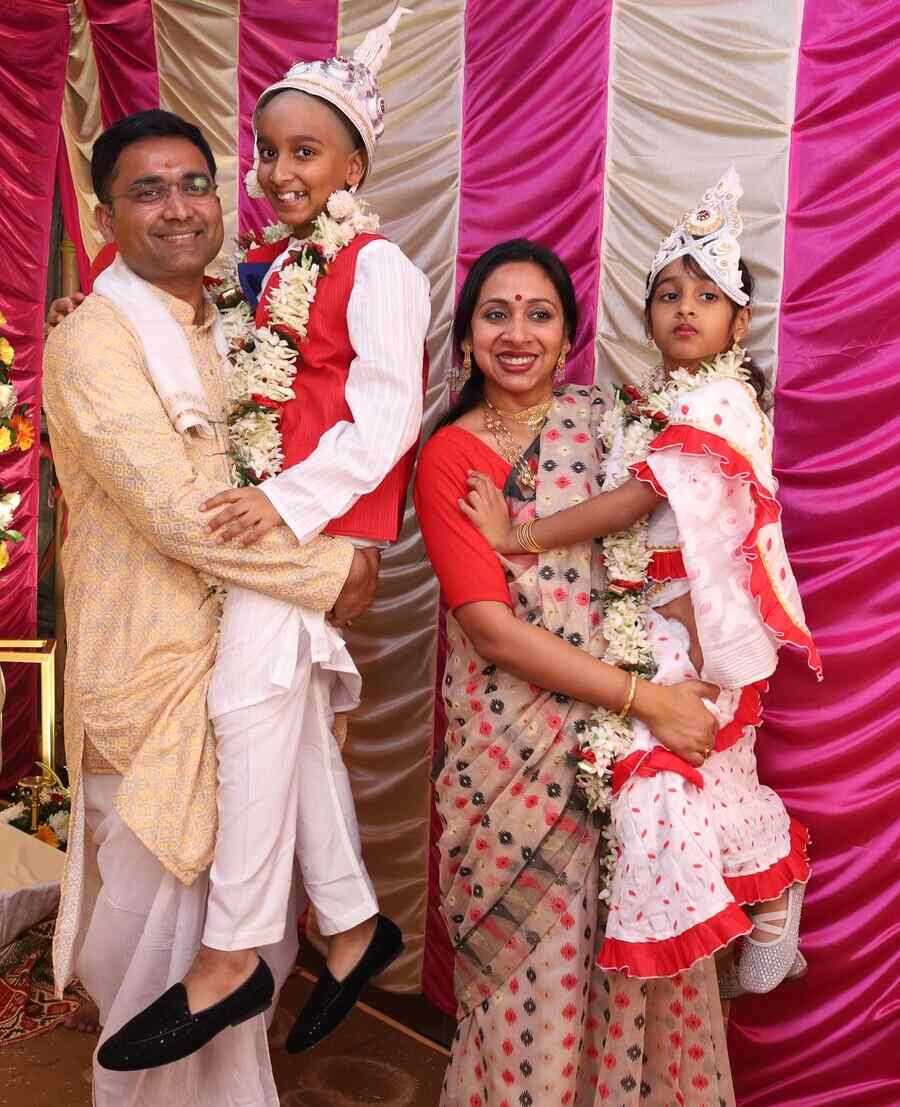

The purpose of the ceremony was to mark the beginning of Hrid and Heeya’s new journey towards intellectual awakening

“We started reading up to understand the reason behind this custom, and how entangled it was to gender and caste. To our surprise, the sources of Vedic literature had no discrimination, and both boys and girls could wear the poite as long as they chose to accept the learning that came with it. Upanayan translated to the opening of the intellectual third eye,” remarked Ananda. The couple got a note of validation from Muktipada Chakraborty, the head priest of Delhi’s CR Park Kali Temple, who had guided Sohini’s family for decades, and is a PhD-qualified Vedacharya and author. “He read out parts from ancient scriptures that proved that there were no inherent restrictions around caste and gender. It pushed us to wonder, if our kids are doing everything together, why not this? It also validated that what we were planning wasn’t unprecedented,” Sohini said.

Bringing together family and society

The biggest challenge was to ensure that Ananda’s family, who had followed the custom religiously for generations, and Sohini’s family, who had never practiced it, would be on the same page. “We were very conscious of how the poite has historically been intertwined with caste, and wanted both sides to feel respected and acknowledged by ensuring that there was no correlation with our surnames. The only way to do so was to interpret the poite in our own way, as something that would hold weight for the entire family,” explained Ananda.

This wasn’t a first for the couple, as they had tweaked their own marriage ceremony, doing away with several customs like the bidaai to make it more contemporary. Similarly, for their children’s poite, they removed the rituals that used the ghunghat, which is considered discriminatory against non-Brahmins.

During their wedding, Ananda and Sohini chose not to conform to certain ceremonies like the ‘bidaai’

Getting society on board proved to be just as challenging. The couple recounted how wishes poured in from many, but only for Hrid, when they shared the ceremony’s invite on Facebook. “That is when we realised that we shouldn’t be subtle about it, and ensure that everyone knows that our son, and our daughter will be participating in this ceremony. Thankfully, our families were supportive,” said Ananda, with a smile.

After speaking to their families, the couple started preparing for a poite ceremony that would be truly egalitarian, and where every ritual would be scrutinised for its relevance in today’s world. A ceremony that wouldn’t define an individual by their surname, but their thoughts. “Our principal question while planning everything was, ‘What will the children gain from this?’,” explained Sohini.

Their views even surprised the purohit appointed for the ceremony, who confessed that he’d never done or seen the ceremony for a girl. “Initially, he treated Heeya’s poite secondary to Hrid’s, and we had to firmly emphasise that both kids would get equal importance. Following that, he enthusiastically came on board,” said Ananda.

Celebrating roots and tradition

The couple’s enthusiasm was shared by the kids. Despite having a Western education and living outside India, both of them take an active interest in their Bengali roots — Hrid even insisted on shaving his head for the poite. Their connection to their roots is down to the couple’s decision to expose them to the culture they grew up with. “They [Hrid and Heeya] have a very American life in Seattle, and it was challenging to maintain that connection because Kolkata felt like a different world. We consciously chose to send them to a Bengali school where I teach the language. Ekhon ora Bangla porte o pare! (Now, they can read Bengali!) In fact, the last few times we have visited Kolkata, they have bid the city a tearful goodbye,” said a beaming Ananda.

Through the ceremony, Ananda and Sohini hope to see their children more connected to their roots, while valuing the effort it takes to earn knowledge

It is this connection that prompted the kids to sit for the upanayan puja all day, without raising a single complaint. “They’ve exhibited immense discipline. On the night of the ceremony, they only ate what they got in bhikka, to normalise the hardship that comes with learning. I even told them that they can’t say no to homework anymore,” joked Sohini.

The spirit of equality extended from the rituals to the organisation, with the entire staff, including the photographers, waiters and chef sporting a ‘Justice for RG Kar’ badge.

The duo also don’t believe in sugarcoating things, and are in the process of explaining the caste system to their kids in the most age-appropriate way possible. “They aren’t burdened by caste in Seattle, so we don’t want them to carry its full weight yet. At the same time, we don’t want to hide it, and want to give them as much information as they can process. In fact, they are the ones who questioned why sometimes the domestic help in Kolkata was treated in a certain way, prompting us to be more mindful of bringing equality to our home. We hope to make them more aware going forward, so that they can bring true change,” Sohini signed off.