“Food brings people, cities and nations together, breaking bread or eating with people known or unknown, is one of the greatest inventions of humanity”

— Rakhi Purnima Dasgupta

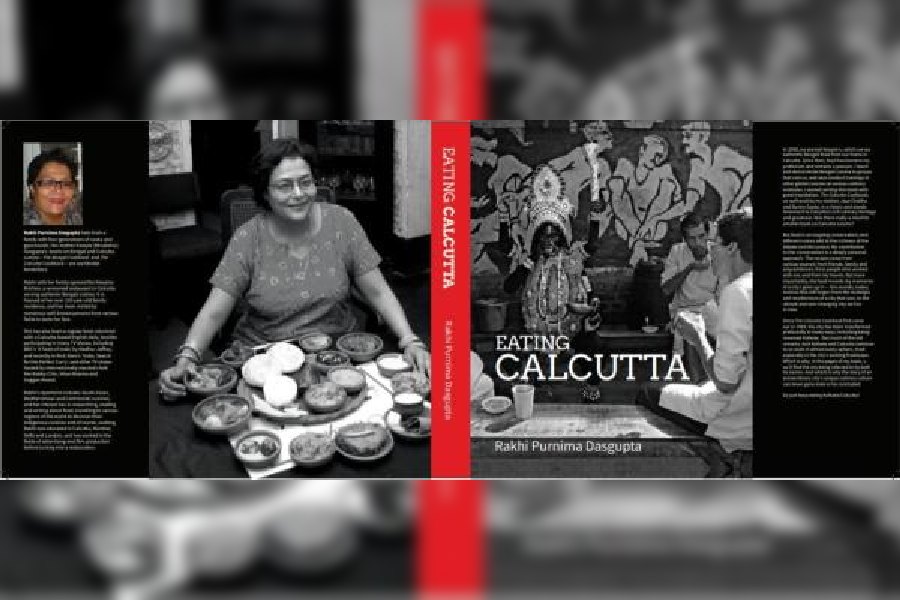

Eating Calcutta is an anthology of sorts. It has all the makings of an orchestra that incorporates diverse talents and energies but excels under the innovative genius of a competent conductor. While the book carries interesting, easily accessible essays by those who are interested in the fields they have written about, deftly incorporating anecdotes, the uncluttered style at once puts the reader at ease. From the author’s foreword, she seduces the reader effectively when she traces her family history with food and invokes six generations of forefathers and mothers to usher her reader into her kitchen and pour out her heart about her deep and abiding bond with food which is umbilical.

Rakhi’s raspy voice still rings in my ears after three years when we discussed the vegetarian fare that was once forced on the widows of Bengal. We go back a long way; she was my classmate in Loreto House. Her wicked sense of humour and her intuitive knowledge and passion about food made her a fitting person to discuss my research on food. This book has been a long time coming.

The author confesses: “My passion for food developed when I was studying in London. The hostel food was bad — bland Britishstodge! And like many other students, I would yearn for familiar tastes, scents and sounds of food from home. So I started cooking for friends and hostel mates in the student kitchen. I come from a family of superb cooks going back six generations. As a child, being the youngest in my family, I was rarely allowed into the kitchen!”

This sentiment resonates across the globe now. A Master’s scholar in my class, Raka Mukherjee, who is now pursuing graduate studies at the University of Manchester, said: “British food is so boring, a few of us from Calcutta spend fun times rustling up good quality Indian food on weekends. I was never allowed to go to the kitchen when I was in Calcutta. It was my mother’s domain. Now I feel creative and satisfied to cook a good chicken curry and vegetables that are so much more appealing than the same old fish ’n’ chips.”

Raka echoes Rakhi’s underlying story, which the author cleverly reiterates by her use of a multiplicity of voices in Eating Calcutta, from Ian Zachariah on the Jewish cuisine of Calcutta to Mudar Patherya on Bohri cuisine, and Jennifer Huang who speaks of one of the most traditional Chinese family restaurants. There are chapters by Errol O’Brien who has the reader mesmerised by the melting pot that is Anglo-Indian food, and Oindrilla Dutt who maps the palimpsest of West Bengal’s history and geography by tracking places that make their own unique mishtis that Bengalis are defined by. The chapters by Aban Desai on Parsi food, and Rita Bhimani on Calcutta club cuisine really put the city on the page.

Their polyphonic narrative is so compelling that I suspect the book would be just as relevant to my students at the University of Toronto who are diasporic South Asians in a home away from home, just as the Jewish, the Anglo-Indians, the Muslims, the Parsees might think themselves to be.

Rakhi is on point when she states: “My mother Minakshie Dasgupta (Kewpie), after whom our restaurant is named, wrote two outstanding English cookbooks on Bengali food and Calcutta cuisines: Bangla Ranna and The Calcutta Cookbook, both of which have gone into multiple editions. She was an innovative and formidable chef. My father, Pratip Kumar Dasgupta (Mithu), along with whom my sister Pia Promina and I began the restaurant Kewpie’s, was not only a good cook but a true gourmet. Both my parents taught me how to appreciate food from all over the world and are the primary motivators of my abiding interest in my culinary heritage.”

The author adds, “My brother Chandradip dreamt of food! He went to a catering college and was the first to start the family food business. My sister Pia Promina excels in the field of confectionery. Since The Calcutta Cookbook first came out in 1994, the city has been transformed profoundly in many ways, including being renamed Kolkata. But much of the old remains. And Kolkata and Calcutta continue to co-exist in almost every sphere, most especially in the city’s exciting foodscape.”

The chapter headings are as inventive as their content. Thus we have ‘A Pinch of the East; A Dash of the West: Anglo-Indian Cuisine’; ‘The Cutting Edge of Club Cuisine’; ‘Dim Sum Means ‘To Touch the Heart’’ by Katy Lai Roy; ‘Living and Eating by the Code of the Thaal: Bohri Cuisine’; Rakhi’s chapter, ‘Calcutta Vegetarian The Bengali Way’; ‘Mughlai Miracle’ by Nondon Bagchi; ‘Park Street: Still Crazy After All These Years’ by Arundhati Ray; and ‘Eating Calcutta: A Feast that Never Grows Stale’ by Shaun Kenworthy.

Nondon Bagchi’s chapter paints a vivid picture of our eating habits: “In Calcutta, the place to go for Iftar feasting is Zakaria Street in the area around the Bara Masjid (Big Mosque, as the stately old Nakhoda Mosque is popularly referred to). I have been there several times carrying containers from home and have done some serious buying, so that I return with haleem made in at least six ways, including with goat brain.”

The renowned academic and writer, the late Sara Suleri, in her memorable memoir Meatless Days explains how food can define personal history and national geography. In keeping with the specific places which have earned themselves fame over the production of a specific kind of food item, whether it is cheese or wine, Oindrilla Dutt, in the chapter ‘Sweet Obsession’ provides a wonderful litany that connects specific sweetmeats to cities which are famous for these sweets: “West Bengal is probably the only state in India where every district boasts of its own, special sweet offering. Burdwan has given us sitabhog and mihidana; Shaktigarh’s (also in Burdwan district) speciality is the langcha; from Joynagar in the South 24-Parganas comes moa (a winter speciality, and not to be confused with the other variety of moa, made with puffed rice bound by molten liquid palm sugar or nolen gur) and Hooghly district’s Chandernagore is renowned for jolbhora. Shorbhaja and shorpuria have their origins in Krishnanagar in Nadia district and the chhana bora hails from Murshidabad.”

Food in theoretical terms is a great link to memories of home and belonging. Roland Barthes, the smart Frenchman who lit up scholars’ lives by reminiscing the taste of delectable madeleines dipped in tea, might have giggled at the synchronicity that the articulate and erudite Rita Bhimani invokes, when she observes: “Clubs are very much a part of this ‘coming home’ experience. And the chance to enjoy the old favourite foods — sitting at the Tolly Shamiana and gorging on the triple-decker toasted Club Sandwich stuffed with pink ham, just-runny fried egg, cheese and much more while looking out on the greens.”

One of this city’s most respected food aficionados and public relations experts, Rita Bhimani said to me as we revisited the gregarious and passionate gourmet and gourmand’s life: “Rakhi was synonymous with the joy of cooking, the passion for entertaining, the art of enjoying a life full of culinary excellence, entrepreneurial oomph, her ready participation in food shows of great import, and appearance in numerous events, her deftness with the pen as a prolific food columnist, and wearing lightly the multigenerational inheritance of family gastronomy. Kewpie mashi’s influence was of course phenomenal on Rakhi, and my copy of Bangla Ranna is now much thumbed and leather bound and a ready reckoner. It was Rakhi who was to become our reckoner on specialist Bengali and occasional Thai delights. Her enthusiasm never flagged, and her inclusivity had many of us write for her book Eating Calcutta. I just loved the name — a publication which she could not, alas, see in print. My piece on club cuisine in this book seems so bland after the memories of Rakhi’s finger lickin’ Bong offerings. Will miss her gruff tones laced with humour, on the phone, from 2 Elgin Lane — a hub that must renew her spark, savoir faire and epicurean scintillation.”

There is no one way to skin a cat just as there is no one way to cook machher jhol. Rakhi’s recipes are tantalisingly fusion-istic. But adding garlic to machher jhol is the kind of overwhelming uniqueness that does not sit comfortably with traditional Bengali recipes. Be that as it may, she brings a certain je ne sais quoi to the creation of her cuisine which some readers might be seduced by and some not.

Publisher Gautam Jatia of Starmark says that he has supported the book because of Rakhi’s passion and interest in food. This book is dedicated to the generation that will hopefully take the baton from her — her nephew Hrisheet Pranav Barve, and her two sons Azan Khan and Deep Chakraborty, may you enjoy and cherish your culinary heritage.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College

Eating Calcutta will be in bookstores in early 2024