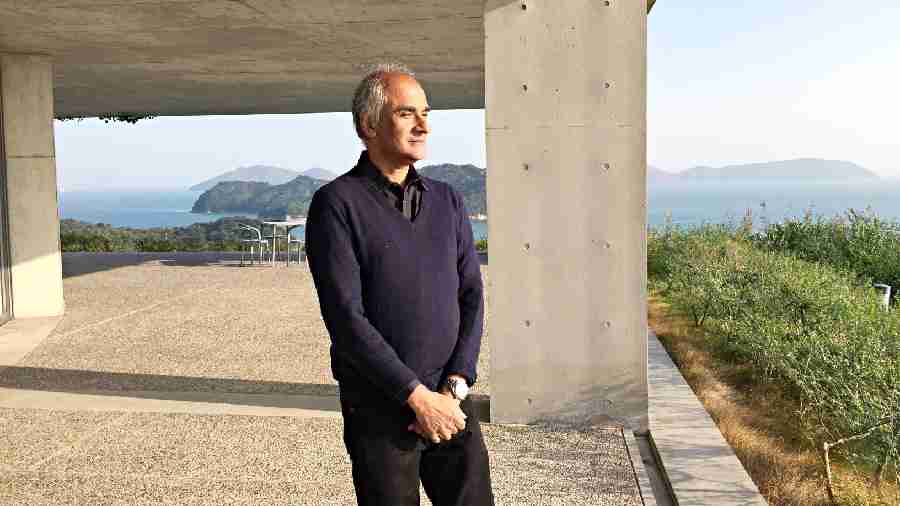

With his engrossing new book The Half-Known Life: In Search Of Paradise hitting the bookstores a few days ago, Pico Iyer was once again doing what he has done many times before — travelling furiously and meeting loyal fans on his North American book tour. t2oS caught up with him while he was in New York to talk about his latest work, paradise, stillness, philosophies and more. Excerpts.

It is striking that the idea of paradise is signposted in the title of your new book, The Half-Known Life: In Search Of Paradise. From the earlier haunting and urgent searches for stillness in novels like Video Night in Kathmandu and Abandon to now, has your quest been to find the mystic pool of light in a dark and fragile world?

As such a loyal reader of my work, you see perfectly how much it’s all part of a single sustained enquiry: the first main chapter of my first book, 36 years ago, and my first back-page essay for Time magazine, at around the same time, both turned around paradise. In those days, I was largely concerned with how the visitor’s delighted holiday paradise was likely to be real life. Not so easy for the local (who perhaps dreamed of the California or Paris from which the visitor had come). Thoughts of paradise can so easily get in the way of finding a paradise right where we stand, and much of what we claim to be paradise is nearly always a projection.

But during the pandemic, all of us were living with death around the corner, whispering softly in our direction, and I longed to find what kind of paradise might be found in the midst of real life and in the face of death.

At some level, we all know that paradise lies within — in a certain way of seeing that translates into a certain way of being: that’s why I have His Holiness the Dalai Lama at the centre of this book, radiating confidence and joy, as well as kindness, in the midst of an unimaginably difficult life. But how can a sense of hope coexist with a strong sense of realism, as His Holiness exemplifies? That’s why I didn’t choose to inspect paradise through the lens of travel-agent arcadias such as Bali or Tahiti or the Seychelles, all of which I’ve been lucky enough to see. I only believe in a paradise that can withstand real life and is open to all.

Pico Iyer’s mother Nandini. Picture courtesy Pico Iyer

How much of your mother’s absence, or should I say presence, made you write The Half-Known Life?

Thank you for such a thoughtful and sympathetic question. This book did very much arise out of the pandemic, and out of the fact that I was spending most of lockdown right by the side of my mother, who was entering her final seasons of life. She had been rushed into hospital in an ambulance, losing blood at a frightening rate, just 20 hours after lockdown was announced in California; I had flown back from our rented flat in suburban Japan to be with her through the next 15 months. What inner resources had I gathered to bring to this extended goodbye?

I had written an earlier book, Autumn Light, about human climate change, as you could call it: the way so many of us are living longer than humans have ever lived before and, therefore, even longer with pain and confusion and displacement, a fate that surely awaits many of us even as so many also deal with the challenge of tending to ageing parents whom we don’t always recognise (and who often Pico Iyer’s mother Nandini. don’t recognise us).

Sometimes I’d sit at my mother’s dinner table, and she’d look right through me, as if I were a ghost. I was reminded, every day, how much of life exists beyond our grasp or explanations — one reason of many this book was called The Half-Known Life.

Can you explain where the spark for this memoir came from and the process which took over writing this meditative recollection. In The Lady and the Monk/Four Seasons in Kyoto, you were seeking stillness in a turning world.

I have long believed — since my second book, The Lady and the Monk, from 1991, which you just mentioned — that life is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows.

One midsummer day my mother came out of her bedroom to join my wife and me in watching, as we did every day, the American quiz show Jeopardy! My mother got many answers correct and when it came to the fiendishly difficult final question — which none of the expert contestants could answer — she cried out, correctly, “Haile Selassie!” and I smiled at her, because I knew she was right.

Then she flashed me and my wife a dazzling smile and bid us “Good night!” and five minutes later she was gone. Death doesn’t have to be sad, if it’s seen as a natural part of life, and the cycle of seasons. Brightness and gratitude can be found in the thick of tumult or confusion.

Could you recall some of the people who appear in your quest to find paradise?

This book is full of people, the ones who kept me company during the pandemic: the Dalai Lama, Thomas Merton, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville. I meet guides in every place I visit — to remind me how little I know and how I’m never in the driver’s seat, in control of my life — and I keep encountering people who touch my heart and share their poignant stories: a Sri Lankan man who looks after a graveyard, a Kashmiri man who maintains dignity and grace even as his wife has just died, an English tour guide who tells of his own terrible loss of a loved one and how he refused to be defeated by it and longed to come back to the place where his heart had been broken to repair his heart and its own paradise.

What are the shared impulses of Mahayana Buddhism, Sufi philosophy and the teachings of your monks of the Benedictine order that you can make sense of?

I’m so glad you mention the Benedictine monks with whom I’ve been regularly staying — more than 100 times — over the past 32 years: I’ve actually almost completed my next book, a quiet brother to this one, about my life with them and the paradises they find within their own walled garden.

I’m not a Christian or a Buddhist or a Muslim, but I find myself deeply moved by the tiny candles in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem by the unstinting care and realism of His Holiness, by the call to prayer and the mosques and shrines I have been lucky to visit in Damascus and Mashhad. The heart of the three religious traditions you mention seems to me to be kindness, care for others. The Bodhisattva gives up the prospect of Nirvana to help those who haven’t attained it yet; the Catholic monks I know tirelessly tend to others, as Mother Teresa and her sisters did on the streets of Calcutta; the Sufis remind us that there’s no division between you and me in the love affair one enjoys with the divine.

Pico Iyer and his wife Hiroko with the Dalai Lama. Picture courtesy Pico Iyer

In Autumn Light, you invited the reader to your apartment in Japan, to the shinto shrines, to the game parlours and unwound the stories about your wife. It was as if we were privileged house guests in your lives...

I’m happy when nothing much happens in my life and I can lead the most boring and changeless (though light-filled) existence possible. I actually was flying back and forth between Japan and California every few weeks during the pandemic, and my job still takes me far and wide. But those travels feel like the surface of life, and its heart and depth seem to take place only when I’m sitting still.

As your questions point out, I’ve really been leading the same life for as long as I’ve been writing: I’ve been in the same two-room flat in Japan for more than 30 years, I’ve been staying in the same monastery for 32 years, I’ve been talking to the Dalai Lama for 48 years, I’ve been driving the same bottom-of-the-line Toyota for almost 28 years. I move through the seasons of life as anyone does — less hair, more weight — but I feel grounded in what doesn’t change. One of the challenges of life, as I’ve often written, is continuing to find excitement, wonder, something new in the midst of familiarity (and the continuity we all need at some level).

How does Hiroko figure in your life? What is a typical day in Pico Iyer’s life like?

As you know so well, I’ve been with my wife Hiroko for more than 35 years. As in any relationship, we’re hoping always to evolve, individually and together, while remaining constant in our connection: as in any dance, one hopes to be moving, growing, even as one also hopes to remain in concert with one’s partner. In some ways, I’ve found exactly the uncluttered and undistracted life I dreamed of when I arrived in Japan in 1987, but it took me a while to see through all my projections and romantic notions to uncover it.

Iyer in Dharamsala. Picture courtesy Pico Iyer

Autumn Light seems to be a powerful amalgamation of Haiku and Zen and it is the perfect precursor to The Half-Known Life. It is perhaps one of your most powerful revelations of finding joy in the most unexpected places...

I really appreciate your kind words about my last narrative book, Autumn Light, which is very much, as this one is, a meditation on how to find joy and sunlight even as we move towards the dark. I should note here, though, one very happy development. That book, as you recall, is about how Hiroko lost her beloved brother when he cut off the entire family, for mysterious reasons, more than 30 years ago.

One chill winter day, just after I published the book, she was travelling two hours from our flat to tend to her parents’ grave when she saw someone who looked strikingly familiar: it was her brother, at the grave, praying before it. He had taken pains not to tell anyone in his family, but clearly he had been discreetly going, often, to tend to hisparents’ memory even as he had publicly cut them all off. It was a lovely surprise and a liberating reminder of all we don’t know and of the many consolations that may lie within that lack of knowledge.

So if you were asked what is at the heart of The Half-Known Life, what would you say?

Life is rich with surprises — this is one theme of The Half-Known Life — and it tends to have richer and more imaginative plans for us than we ever have for it. It’s so easy to dwell on the shocks and disruptions; I wanted to train my gaze on the more hopeful and emancipating moments of unexpectedness. Thank you for such rich and thoughtful questions: it’s such a luxury to engage with someone who has followed my work so faithfully.

In your struggle is your Paradise

In his newest book of journeys through lonely, far-flung and embattled geographies, Pico Iyer, perhaps one of the finest raconteur-travel writer philosophers ever, has hit his stride in his search for paradise like never before.

This time, his adventures straddle an itinerary that selects some of the most disturbing spaces to find peace, places that are a juggernaut of discord, dysfunctionality and gore, mired in contestation, confusion and mayhem.

From Tehran to Belfast, Sri Lanka and North Korea, Iyer takes the reader through a planetary tour of dystopic communities and cultures while trying to find the acme of peace in the spinning vortex.

It’s an unusual path that he forges — this living the axiom of finding the light in the midst of the darkest of forests, of ferreting out jewels in the most dangerous caverns of domination, power and brutality. Why not walk the paved path of comfort and profit, luxury and unfettered beauty of resorts where the perfect answers are easily found by the rich and famous who look for nirvana in easy, bespoke mantras of yoga and New Age yantras?

Because, says Iyer very simply, “seeking a paradise that can withstand real life and is open to all”.

In his engagement with unsettling and unsettled places, Iyer reminds us again and again, that the hope in this book is to spotlight those “who refuse to be broken by life”, whether it’s actresses struggling to live in an often oppressive Iran, or the residents of North Korea, or war-torn Belfast. He may not dwell at length on them, but he hopes that every character in the book, alive or dead, is seen with tenderness and has some wisdom to offer.

Iyer posits that he wanted to see what kind of paradise was plausible in war zones and places of conflict, from Kashmir, and Sri Lanka to Iran, North Korea and Belfast. “I do feel as a traveller that pretty much everyone I meet has something to teach me — and though his book is more about enquiries than people, its companion volume, which I hope will be out in a couple of years, is all people,” he says.

In his lucid language, stamped with Iyeresque grace and concision, he describes the uplifting moments of being transformed by the words crystallised through the unforgettable voice of the driver who drove him to the sepulchre in which Ferdowsi’s body was said to rest, and placed his hand on the cold stone.

“He took off his baseball cap and set it against his heart. Without preamble, in a rich and sonorous baritone, he proceeded to deliver a long sequence of verses from the poem that turns history into myth and vice versa. Everything stopped. For what seemed like minutes we stood rapt.

I have made the world through a paradise of words.

No one has done that but me.

Huge palaces and monuments will fall into disrepair.

But I have made a palace out of words that shall never fade.

Through this I have immortalized Iran.

As his guide in Tehran, Ali, concluded his translation, the driver put on his cap once more and offered Pico a reassuring smile. “I didn’t know if I could sing again,” he explained, in perfect English. “Seven months ago I was diagnosed with cancer of the throat. My doctor advised me not to sing. But when I come here, I have to try. For Ferdowsi. For Iran.”

“A paradise of words: the driver’s incantation might have been expressing the single most urgent impulse that had drawn me here. After years of travel, I’d begun to wonder what kind of paradise can ever be found in a world of unceasing conflict — and whether the very search for it might not simply aggravate our differences,” writes Iyer.

So, the seduction with Iyer comes with a kind of exhilaration that is reigned in. Juxtaposing an entire universe of Persian history, culture and religious and political theocracy, with the geography of encountering the reality of impermanence, the tenuous and indeterminate nature of living and dying and the anxiety of disease and death, Iyer masterfully gathers the binaries of romance and reality to gently show the fellow traveller, the reader, that there is no “other” place, no better time to find paradise, but it is in the fractures and the fissures of sorrow and separation, pain and rupture that paradise might reveal itself to an open-hearted seeker.

Iyer’s long-time friend and soul brother Leonard Cohen might have punctuated Iyer’s understanding of the world when he had said: “Ring the bells that still can ring, Forget your perfect offering, There is a crack in everything, That’s how the light gets in.” Iyer is resolved that the stillness in a whirling world is right here in the centre of our being. He says: “At a time when so many of us try to shout about how much we know and are on top of things, I wrote this book to suggest how little we can be sure of and how much we’re at the mercy of forces far larger than we are — a pandemic, a forest fire, a hurricane. That’s why I end with a Zen teacher telling his students, ‘In your struggle is your paradise.’”

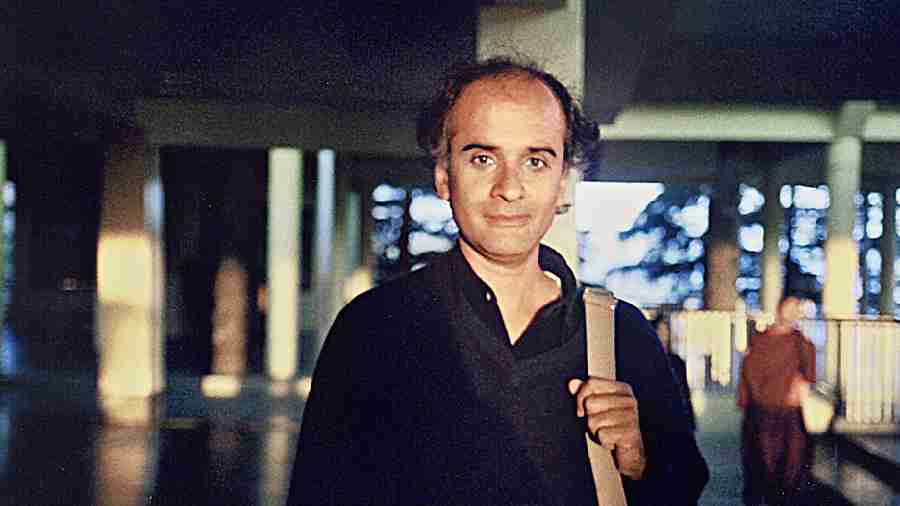

Forty years ago, when I interviewed him across the Pacific, with virulent static in the underground cable under hundreds of feet of ocean he had spoken more or less the same words of wisdom. Now, four decades later Iyer is even more focused on the idea — if that is possible!

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author ofDance of Life and co-author of thebestselling biography Strongman:The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen.She has a PhD in English and SouthAsian Studies from the University ofToronto, where she taught WorldLiterature and Postcolonial Literaturefor many years. She currently lives inCalcutta and teaches MastersEnglish at Loreto College