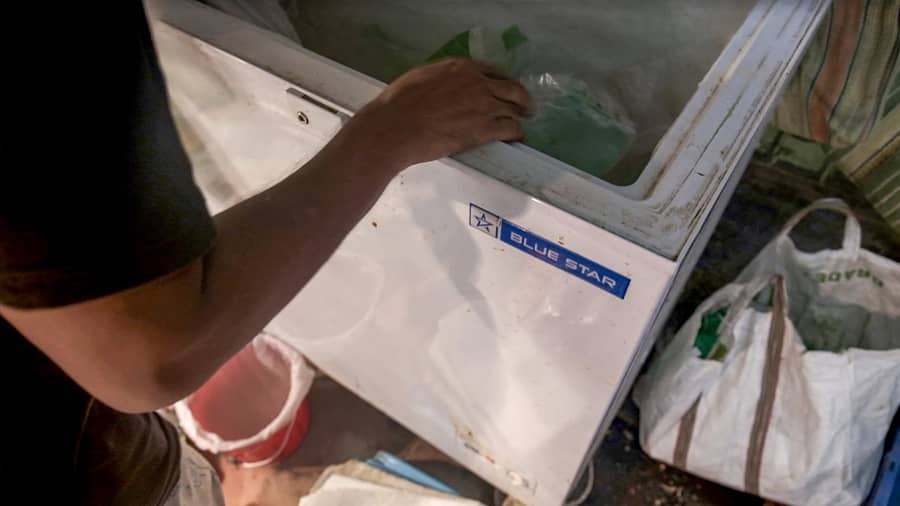

The moment Chandan Pandit enters the Gariahat fish market, he is mobbed. Amidst the chaos and the stench that can only ooze out of a fish market, half-a-dozen fishmongers surround Chandan, desperate to sell him their best catch. But Chandan, who has his own refrigerator for storing fish inside the market — yes, you read that right! — remains unperturbed.

As someone who buys fish worth Rs 40,000 to Rs 50,000 every week — again, you read that right! — for his family, friends, colleagues and even the security guard of his apartment, Chandan knows how to get what he wants as well as who to get it from.

Chandan’s very own refrigerator inside the Gariahat fish market, which he uses to store fish once his two refrigerators at home run out of space Ritagnik Bhattacharya

Once he has seen a fish he likes, Chandan scans it with surgical precision, grabbing it and turning it over to feel its skin and its weight. A quick look at the rest of the catch confirms what he has already guessed: he has his hands on the best. If Arjun was the master at seeing the eye of the fish, Chandan is a master at seeing the whole thing!

“I’ve been fascinated with fish ever since I started going to the fish market as a kid with my grandmother, and then with my father in Kidderpore,” says the 53-year-old Chandan, who moved to an apartment in Gariahat’s Dover Lane in 2007 because it was minutes away from one of the biggest and best fish markets in south Kolkata!

Salmon in Europe, snow crabs in the Arctic, sharks in Brazil… raw fish in Japan

Chandan has sampled fish in 23 different countries, but has not found the sheer variety of fish that he is used to in Kolkata anywhere else Ritagnik Bhattacharya

Having worked in the oil and gas sector for most of his career, Chandan has travelled the world, visiting some 23 countries and sampling fish in all of them. “Apart from Antarctica, I’ve had fish pretty much everywhere else,” chuckles Chandan, who picks salmon in Europe, snow crabs in the Arctic, sharks in Brazil, blue marlin in the Philippines (one of the few countries where it is legal to eat) and raw fish in Japan among his international favourites.

Back home, just like most Bengalis, Chandan loves his ilish and chingri, which he often cooks himself. “I eat all kinds of fish, but due to what’s available most commonly in the market, hilsa and prawns end up being eaten the most, along with crabs and bekti,” says Chandan, who frequently tries out other varieties such as boal, koi, pomfret, gule, madhu bhola and parshe.

Four pieces of fish every morning for breakfast

A peek at what lunch usually looks like for Chandan at home Chandan Pandit

For Chandan, each day begins with four pieces of fish for breakfast, with no hard-and-fast rules about the type of fish or the dish. Lunch is more regimented, with ilish bhapa or chingrir malai curry a constant, besides the quintessential maachher jhol, starring rui (rohita) or katla. For dinner, Chandan’s platter generally consists of fish fry (always made from bekti and never from basa), crabs and chilli fish. Occasionally, Chandan might try out squid (which he cleans himself), recipes centred around bekti maachher kanta (the bones of bekti) and nona ilish (dried hilsa preserved with salt) or have an Italian-style fish barbecue.

Chandan feels that the young generation has not been initiated into the art of buying fish Ritagnik Bhattacharya

Having made it a habit to eat 2kg of fish day in and day out — repeat, you read that right! — he has been moderating his intake of late due to diabetes, sometimes replacing fish in his morning meal with “disgusting oats”.

Chandan rues the waning art of fish-buying. “Everyone wants to get everything online. But with fish, you need to be there in person to check if you’re buying the best product. The problem is that the current generation hasn’t been taught the culture of going to the bazaar and shopping for fish. As a result, they don’t know what to look for, and nor do they know the tricks and trades of bargaining,” explains Chandan.

Know your ‘ilish’ from your ‘chandana’

As a pro-tip, Chandan warns buyers against falling for the ilish-chandana trap, where fishmongers pass off the yellow-tailed chandana, which looks and tastes similar to ilish, as the real ilish, usually at three times the standard price of chandana. He also suggests opting for rupchanda over pomfret, as the former is a far more economical choice.

In terms of more generic advice, Chandan says: “Whenever you’re buying fish, bear in mind that the ones that lose their colour don’t always lose their taste. But if you’re buying ilish and the head turns yellowish or orange-ish for chingri, purchase it without the head. Once you’ve bought the fish and cut it at home, only take out from the refrigerator whatever you intend to cook and eat at a particular time. The worst thing you can do to fish is take it out from the refrigerator, not have it entirely and put it back in.”

Maniktala and Gariahat are great places to buy fish; Maniktala might be better because…

Chandan is worried that price undercutting will eventually lead to the closure of prominent fish markets TT archives

While Chandan habitually shops from the Gariahat market, he acknowledges that the Maniktala fish market is just as good, if not better. “Both Maniktala and Gariahat are great places to buy fish, but Maniktala might be better because north Kolkatans are more particular about their fish than south Kolkatans, who prefer chicken,” reasons Chandan, who estimates that fish markets might become extinct altogether in a decade or more. “Fishmongers get up at two or three in the morning and start selling fish in these markets, but then you have people who buy fish from them and sell them at half the price on the streets. They’re ruining the fish economy by undercutting and putting fishmongers out of business.”

Chandan with his wife Sucharita Pandit at the Thiksey monastery in Ladakh Chandan Pandit

Why have chicken when you can have fish?

When he is not drowning in all things fish, Chandan spends his time analysing stocks. “The only thing that never stops, be it during Covid-19 or some other crisis, is the stock market. Reading stocks is something I’ve taught myself and I try to teach it to my colleagues as well. I’m in a position where I can virtually guarantee that I’ll never lose money,” says Chandan, also a cricket fan and admirer of Virender Sehwag for his “attitude and how he changed the game with his attacking mentality”.

A bit like Sehwag at the crease, Chandan is no-nonsense when asked to make the case for eating more fish. “Nowadays people are obsessed with chicken, but they don’t realise how chicken is made. The grease-like remnants of edible oils and injections are some of the most vital ingredients that go into the chicken that we eat. That’s anything but healthy. Fish, on the other hand, are high in phosphorus and calcium and don’t go through a toxic cycle of production. Moreover, there are so many varieties of fish to try out, so why not have more fish at every possible opportunity!”

As Bengalis, we don’t get involved enough in how fish are bought and sold

Chandan wants Bengalis to get more involved in the fish economy Ritagnik Bhattacharya

Chandan urges Bengalis to care more about fish, an inseparable element of the Kolkata cuisine and culture. “Why are most people who export fish in India ones who don’t even eat fish? One reason is that as Bengalis, we don’t get involved enough in how fish are bought and sold. We don’t look at the entrepreneurial side of things,” laments Chandan.

Spending a couple of hours with Chandan is ample proof that fish is not just an obsession for him on the plate; it is a way of life. “I’ve always felt that if you love something or are passionate about something, you should go all in. Try and find as much as you can about it and learn to manage your knowledge. Take the untrodden path and see where it leads you. Great fish, after all, don’t swim in shallow waters.”