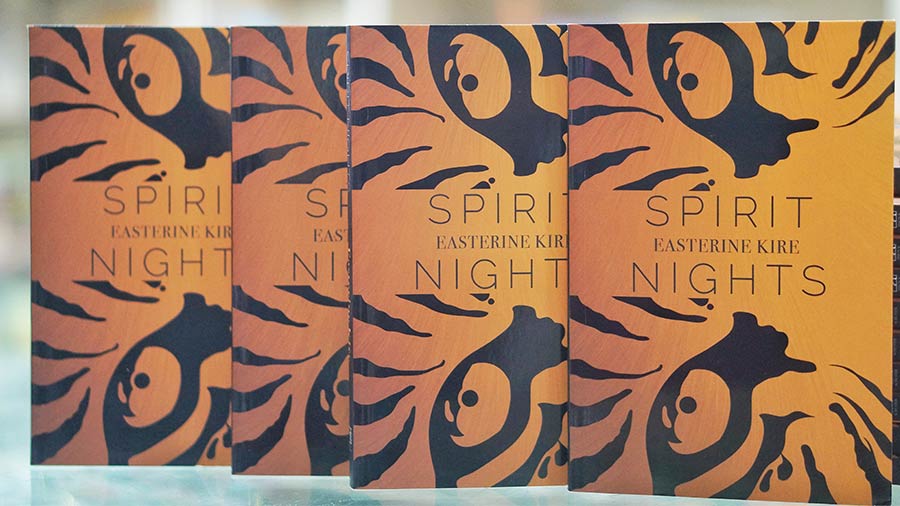

Award-winning Naga author and poet, Easterine Kire was in Kolkata recently for the launch of her book, Spirit Nights, at the cosy Storytellers Bookstore. The Kohima-born author, whose writings focus on the realities of life and folklore from northeast India, also participated in a session on the book. In conversation with My Kolkata, she talked about the inspiration behind her work, the heritage of Naga oral narratives, her world of folklore and history, the peddled image of the Northeast, its impact, and much more.

Edited excerpts from the conversation below…

My Kolkata: How did you find your calling as a writer?

Easterine Kire: I was a big reader and I still am. For some reason, it led me to discover writing. I had studied English literature for my bachelor's and master's. One of the things — which you should not tell students (smiles) — is that the lectures would often get pretty boring, and I pretended to take notes while writing stories. I guess that is where I took off. At about 16, I was writing poetry and all my friends were doing that as well. It’s either just a phase or you continue with it. By 19, I was writing short stories and thoroughly enjoying all of it.

Your writings bring forth a lot of Naga social realities. How much of it, do you think, is still away from popular knowledge or understanding?

We have unwritten history, which was passed on through oral narratives. It’s not that we did not have history or we did not have literature but everything was narrated. It was relayed by word of mouth in a very formal and cultural setting, of people sitting around a fireplace listening to these stories being narrated by someone with the knowledge. It was an art, which eventually died out with the Japanese invasion, the Second World War and everything else that came along, silencing our narratives. At a later stage in my life, I felt this urgency to write down our history. I started off with historical novels and wandered into proper fiction, because with the folklore base I had, it was easy for me to get into that.

Your narratives bear a strong feminist understanding of the Naga society. How distanced is it from the popular urban understanding of the same?

Honestly, I don't write with feminism as an agenda. In our society and our culture, we have a lot of powerful women and the position of women has always been strong. There has not been a struggle when it comes to empowerment and, thus, my narratives have strong female characters.

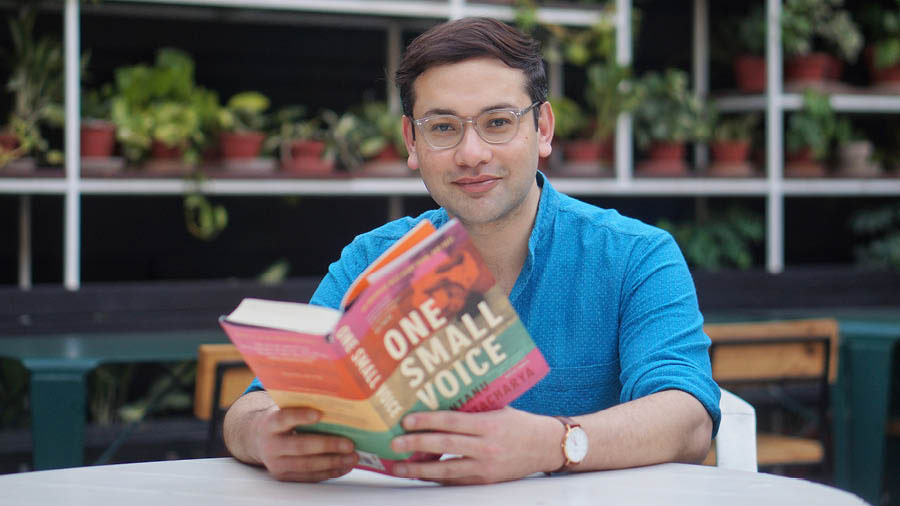

Easterine Kire in conversation with (right) Amrita Mukherjee

Do you think you have a certain sense of responsibility that you hold with your work, or is it a creative space which is independently just yours?

I have been born into a time where I experienced this transition from the oral to the written. So, we saw the beginning of the scholarly writings, works in the Seventies, and we started to write our novels much like African writers like (Chinua) Achebe did. Our cultures are very close and we saw them doing this interestingly and, for me, in a very relevant way. I tried doing the same and it worked. But the timing of my introduction to this space formed the most crucial element to all of it.

Is there still a major portion of the Naga oral narratives waiting to be scripted?

Yes, to some extent. There was so much space between the two times — from when everything was being passed down orally to when we actually started writing. We realised the importance of documenting in writing, and that we were losing out on something very precious. But so much of it was lost in that space of transition. I’m very grateful for whatever we have managed to write down till date, but I’m always aware of the loss, the accounts that were lost with the narrators. It is not just stories or folktales, it is a whole body of literature with its proverbs, sayings, and a uniquely poetic way of thinking. The more people got exposed to modern education, the memory which carried these oral narratives, faded, contributing to the loss.

Could you talk to us about the discrimination against people from the Northeast and its reflection on popular culture?

The big harm that has been done to the people of the Northeast is that during the 1970s and ‘80s, tabloids and magazines made their bread and butter from the Northeast. They sold this sensational, offensive and conflict-ridden image of northeast India to the rest of the country, and that’s being perpetuated till date. In the past, we have had publishers who just wanted us to write about conflict, and if we didn’t they did not want to publish us. The tabloids showed a burning image of the Northeast and that has harmed generations, shaping the thinking and the attitude the general populace has about us. Gradually, people started travelling, living here, and saw the reality for what it is and slowly the idea morphed. But being able to travel can be a luxury, and not everybody has that.

Could you talk to us a bit about the jazz poetry band Jazzpoesi?

(Laughs) We just got together on a summer day and I had some poems which I had written for another jazz musician friend of mine. He sent me the compositions, while I wrote the poems. My boys (her bandmates on the drums and saxophone) liked them and added their own tunes to it. We went on tours, kept performing. It is something impromptu. Sometimes we play on stage because we don’t know what we are about to do the very next moment. It is a lot of fun and lets you be yourself and free. We have few recordings of the sessions on the internet and those are rough and intimate, exactly how we like it.

Kire’s latest book, ‘Spirit Nights’, is a fiction novel about a little village facing a spiritual battle

Could you give us a teaser into your new book, Spirit Nights ?

It is about a period of darkness and about a prophecy related to a little village, which foretells that one day darkness will take over the village and catch them unaware, and they will have to be spiritually strong to resist the ‘darkness’. It’s about a spiritual battle, more than a physical one. The village finds itself in the middle of darkness, in broad daylight. The villagers run back to the village to save themselves, each other and resist the darkness, which stands as a metaphor for so many things. When they start living it, they realise the shades and the ‘darknesses’ that exist in the life of people.