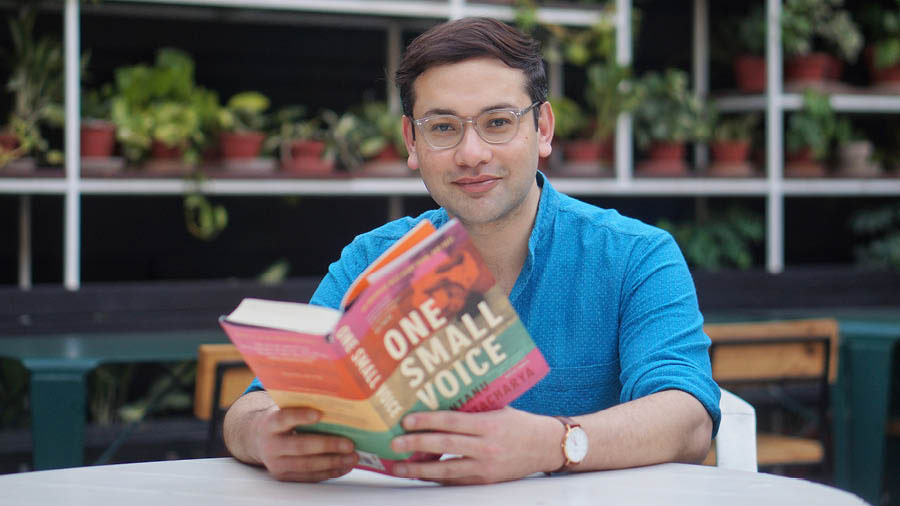

Santanu Bhattacharya’s relationship with Kolkata is complex enough for him to describe it as “funny”. Having moved here when he was 11, Bhattacharya left the city to study when he was 18. As a child, the author hated the heat and traffic. “I hated being so close to relatives. I hated the fact that I only spoke English. People here spoke Bangla all the time.” Only when he was 14 did Bhattacharya finally start warming up to Kolkata. “I started making friends around that time, hanging out with them after tuition classes, and all of that teenage stuff. Whenever I come back, a teenage part of me comes alive.”

Since Bhattacharya, 41, has never lived here as an adult, he sometimes feels he has not been able to keep up with the city: “I don't know what's in. I don't know what's the latest restaurant to go to because I eat at home. My parents live in Salt Lake. When I'm here, I spend a lot of time with them.” Even though Bhattacharya is in the city to release his debut novel, One Small Voice, on Monday, he says he has surrendered to the comforts of family life. “I like being at home, eating my shukto bhaat.”

Speaking to My Kolkata earlier this week, Bhattacharya went on to add that almost all his family is based in the city. “We don't even have to go to Durgapur, Asansol or Murshidabad to see relatives. Everyone is here. So, for me, Kolkata has always been a place of family.” Being in Kolkata this April, he says, has helped him take his mind off the book. “I think I am so ambitious about this book and about my writing, that everything seems like a stepping stone to something else. So, in a way, I am learning to sit back and enjoy whatever success has come my way. But Kolkata has also helped me tune out of all that a little.”

After winning the Mo Siewcharran Prize in 2021, Bhattacharya got a publishing deal for his novel with Penguin UK. “The story itself is ten years old, but I had put it away for five years. I started writing in 2017. I wrote by myself for four years and then one year with the publisher.” Writing the book wasn’t easy for Bhattacharya. He had moved to Britain in 2015 to pursue a Master’s in Public Policy at the University of Oxford. When starting to write the book, Bhattacharya felt like “a newcomer, an immigrant and a foreigner”. He was also in no position to give up his nine-to-five job in educational consultancy: “I wrote from 4 am to 8 am every day and then logged into work. Sometimes a chapter would make me cry, and then I would just wipe my tears and log into a Zoom call during the pandemic.”

In the two months since its release, One Small Voice has received praise from the likes of Max Porter and The Guardian. The Observer has even included it in its list of best 2023 debut novels. Bhattacharya has been lauded not only for the political immediacy of his novel but also for its emotional urgency. By giving Indian millennials a national register, and by mapping private trauma against the canvas of public violence, Bhattacharya has fictionalised and psychologised India’s history as a deep, personal anguish.

‘Lean on what you know’

Bhattacharya’s protagonist, Shubhankar Trivedi, shares several similarities with his author. They both start off their careers as engineers, each deciding the profession is not for them. They are both “artists by temperament”. Shubhankar, like Bhattacharya, goes to Mumbai and lives with flatmates. “We have similar quandaries. Shubhankar is completely fictional, but his practical realities are mine. That saved me the research. If I made him something completely different, say a microbiologist, I’d have to say something about microbiology. I just said, ‘Lean on what you know,’” laughs Bhattacharya. Importantly, perhaps, both he and Shubhankar were ten when the Babri Masjid was demolished in Ayodhya in 1992.

The shadow of mob violence looms large over the book. One Small Voice begins with Shubhankar asking innocent yet profound questions: “What happened to the Babri Masjid? If the mosque could crumble and fall, what chance did their house have?” Soon enough, the child’s curiosity and concern take on the shape of horror and terror. He sees a Muslim tailor being burnt alive by members of his extended family in Lucknow. Shubhankar never tells anyone what he has seen, and this secret festers inside him like a neglected and open wound. Years later, he becomes a victim of public violence himself. Living in Mumbai, he is practically lynched during the anti-migrant riots that come to consume the city.

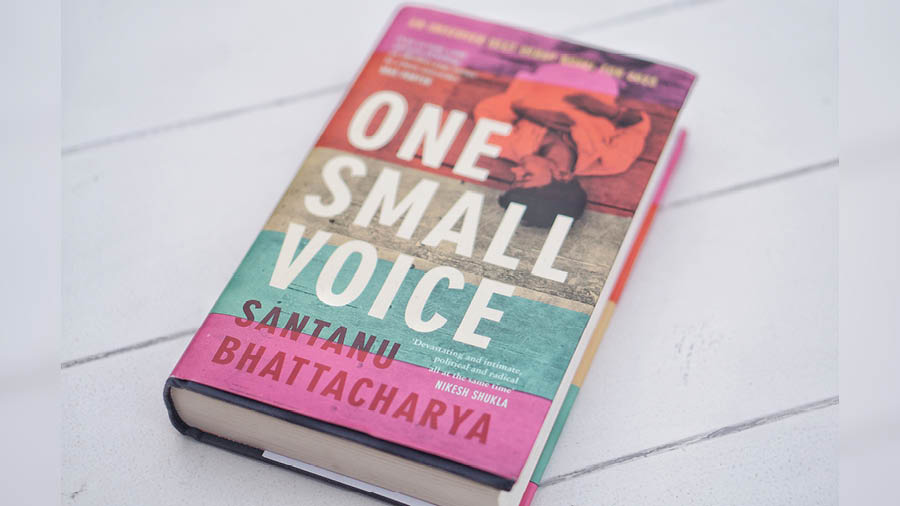

‘One Small Voice’, Santanu Bhattacharya, Fig Tree (Penguin), Rs 699, 385 pages

Bhattacharya describes these two incidents as the “tent poles” of his plot. By bracketing his book with these occurrences, the author attempts to show us that violence seldom stops to check for privilege when wreaking its havoc. None of Shubhankar’s advantages — neither his caste or class, nor his gender or education — come to his rescue when he is in dire need of protection. “I wanted to meditate on what it feels like in a person's mind and body who is living with that trauma of public violence,” says Bhattacharya. “I feel like there's a lot written on private violence, but public violence is something that is only reported. We never know the stories. What does it mean to be on the wrong side of an attack?”

When trying to come to terms with the brutality he witnesses as a child, Shubhankar scans the papers, only to see that the “news was of deaths, not of the dead”. An avid reader of newspapers ever since he was young, Bhattacharya says he is struck by how mass violence removes personal specificities. “It obliterates both the aggressor and the victim. We don't know where the aggressors have come from or who they are. What drives somebody to get on top of a non-functional 16th-century monument, and break it down with their own hands? Similarly, we don't know where the victims are coming from.”

Bhattacharya, a first-time novelist, has written a book that is both brave and humane

According to Bhattacharya, fiction can fill the vacuum that is left behind by public discourse. He feels that the task of novelists or storytellers is to “bring to life both sides and see them interact, both before and after the incident.” Bhattacharya’s predilection for big-budget Bollywood movies perhaps explains why certain sections of his book brim with scenes that are larger than life and cinematic, but, in the end, it is the author’s love for detail that shines through. At one point during our conversation, Bhattacharya mentions Rituparno Ghosh’s 1997 film Dahan. “The film tells the story of a woman who gets assaulted outside the Tollygunge Metro station. Ghosh, it is said, was inspired by a real-life incident. But what he made from it was so beautiful. The details are still imprinted on my mind — where she comes from, what her family looks like, the little things she goes through. That is the power of storytelling which a news report can never capture.”

Swimming against the tide

Though Bhattacharya never stops giving us the particulars of Shubhankar’s trauma, he admits that the story he really wants to tell is of a bruised and fractured nation. “I wanted to write about India, especially post-1990 India.” In order to widen the scope of One Small Voice, Bhattacharya makes human two broad episodes that have defined India’s recent history — economic liberalisation and the rise of the Hindu right. “I wanted to talk about how those two very different things really went hand in hand, ultimately bringing us to where we are now. Despite economic prosperity, we somehow haven't been able to politically embrace a more liberal worldview. Politically, we've become more and more cornered. I wanted to talk about the tension and friction between those two very strong waves.”

It isn’t only Babri and the anti-north Indian riots in Maharashtra that propel One Small Voice toward its denouement. Bhattacharya even stops to mention the 2001 Indian Parliament attack. The Godhra riots of 2002 become a plot point, too. “I also wanted to write about this constant sense of violence that we’ve been living with throughout all those decades. Violence always seemed around the corner. Take Bombay, for instance. You had the bomb blasts in 1993, but then also the train blasts of 2006. Something was always happening. I wanted to ground the narrative in the news of the day and time.”

Bhattacharya also wanted to put down on paper our recent turbulence, “so that we remember”. Making the case that “society is very good with amnesia”, Bhattacharya, a first-time novelist, says he wants his book to pull from under the rug uncomfortable truths that we are often quick to sweep. “This is also recent history. Recent history is always contentious. We haven't resolved it. So, we can talk about colonialism and Partition at length. As a nation, we know who was on the right and who was on the wrong, but for more recent events, we don't know yet. It never gets talked about. I wanted to memorialise all things that happened. People lost their lives. I wanted to bring that back to our reality.”

Bhattacharya is in Kolkata to release the novel at Starmark (South City) on April 17

One Small Voice has hit the shelves in bookstores at a time when several Indians feel forced to censor their political views and opinions. Bhattacharya, thankfully, never seems to want to disguise his politics. The stand he takes is humane, but it is also brave. The author, for his part, makes a distinction between personal and political courage. “It takes a lot of emotional wherewithal, especially as a first-time writer, to sit in a room all by yourself, and type out draft after draft of violence and trauma. I managed that by also talking about the joys and happiness that a young person feels in a new city, when making friends and discovering love and sex. For me, life is not just about the deep, dark things.”

For Bhattacharya, life is a thali. “It goes all the way from bitter to the sweet, from spicy to savoury, and I wanted to talk about life as a combination of all those things, but then came the question: ‘Am I putting myself in hot water, politically?’” Bhattacharya says his naivety inadvertently helped him soldier on. As a debut novelist who didn’t know if his work was ever going to be published, he thought it was best to be true to his story and say all that he wanted to. “Maybe if I was more established, I would have cut more corners and been a lot more conscious. But I did get panicky, especially after Salman Rushdie was stabbed last August. I had to acknowledge that this stuff happens to writers, too.”

In an effort to soothe his nerves, Bhattacharya repeatedly reminded himself that he was only writing a story. “There are foot soldiers out there who are putting themselves in harm's way, day in and day out, fighting for minority rights, for gay rights, fighting for farmers. There were women and students who turned up. They showed that activism in this country can be both personal and collective. For me, a book is a rather comfortable and cowardly way to make a point. I'm not on the streets. I'm not being sprayed with tear gas. I’m not being lathi-chargeḍ. But my sense is if they can do it, maybe we all can.”