At the traditional Netaji birthday assembly on January 23 this year, after professor Sugata Bose had presented his illustrated address ‘Netaji’s Vision for Asia’, all eyes were on a delicate figure seated in front in an ivory sari — Asha-san from the Rani of Jhansi Regiment of Netaji Subhas Bose’s INA. Lieutenant Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry, with her neatly coiffured silver tresses dappled in the late morning sun, lit up the congregation with her spontaneous marching rendering of Kadam kadam badhaye ja ... Sung so spiritedly by the 95-year-old, that on conclusion, there was a standing ovation for her.

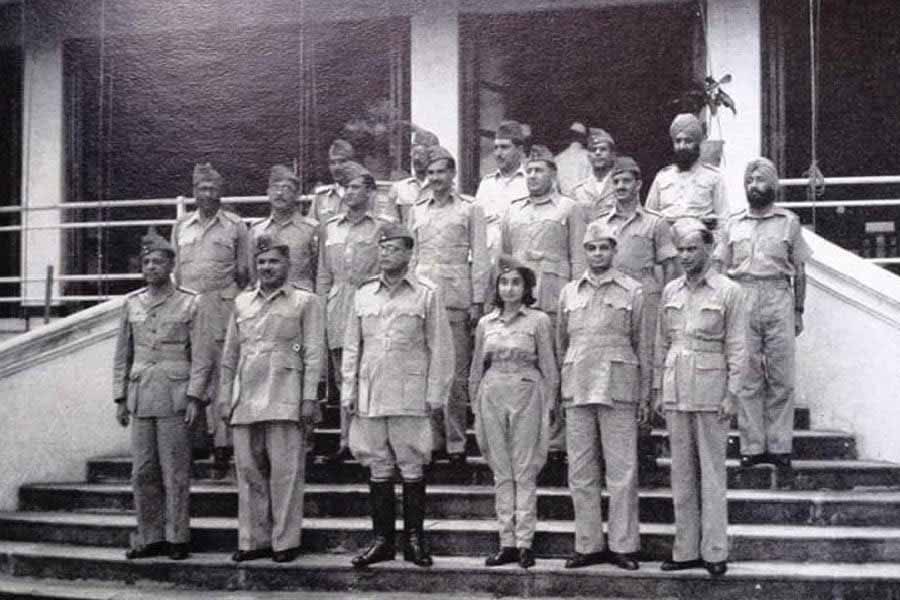

The Azad Hind cabinet

Singing seems to come so naturally to her. I got a chance to hear her hum: Shubh sukh chain ki barkha barse, used at one time as the national anthem of the Provisional Government of Free India led by Netaji. She sang this when they reached Kolkata in 1946 at the Hindustan Park home of her grandmother Urmila Devi, sister of Chittaranjan Das. On many occasions before (at the send-off her college gave her as she prepared to join the theatre of war) and thereafter, too. And I was also able to record her singing a couple of panktis of “Subhas ji, Subhas ji” thus:

Subhas ji, Subhas ji, woh jane Hind aa gaye

Hain naaz jispe Hind ko, woh shaan Hind aa gaye

This had been originally composed by the soldiers of Azad Hind Fauj dedicated to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to welcome him back to Singapore on July 3, 1943.

Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry being felicitated by President Pranab Mukherjee and Ram Nath Kovind

But it was beyond song and more the thrust of the bayonet that attracted the 15-year-old Asha, living in Japan in the midst of the Second World War, to be aroused by patriotism. Still too young to jump into the fray. But by the time she was 17, she was ready to join the Rani Jhansi Regiment and fight for the freedom of India.

My interaction with Asha-san proved to be a triple whammy. The presence of her son, Sanjay Choudhry, who has amassed much of the relevant information, trawled the archives, gathered and assimilated memories of his mother’s life in Japan and the dramatis personae in her life; the very able and articulate translator of The War Diary — Tanvi Srivastava, Asha-san’s granddaughter-in-law, who is a versatile short story writer and of course the diehard Asha-san herself, quietly but firmly intervening, like the tendril of a cherry blossom branch, with her recall of key incidents.

It is thus the song, more than the singer that resonates with us as we pause to reflect on Japan in the war years, where a feisty teenager revved up the courage to endure hardship and shortage of food, where regular sirens sent them scurrying into the trenches, where learning came piecemeal but large doses of patriotism overrode it all.

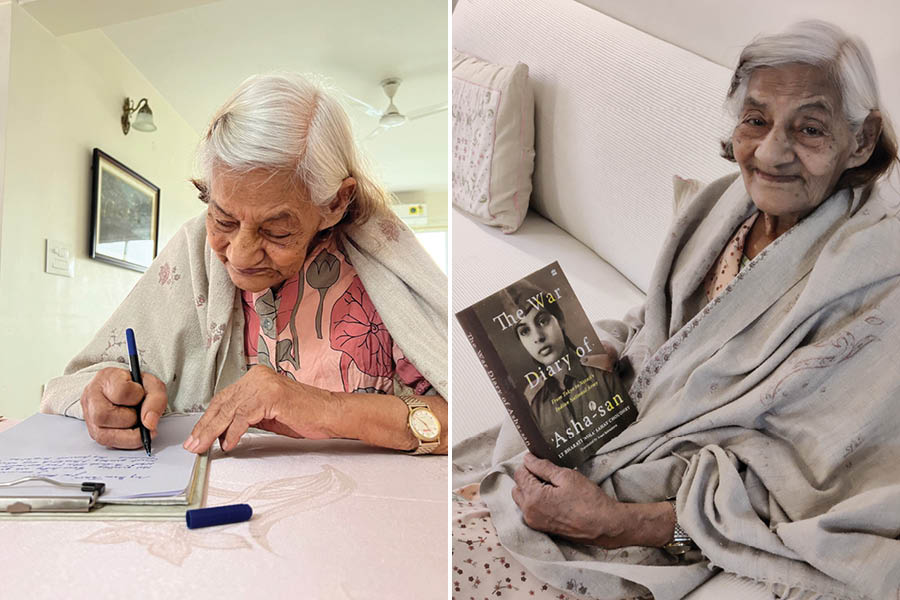

Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry writing the book and (right) after its publication

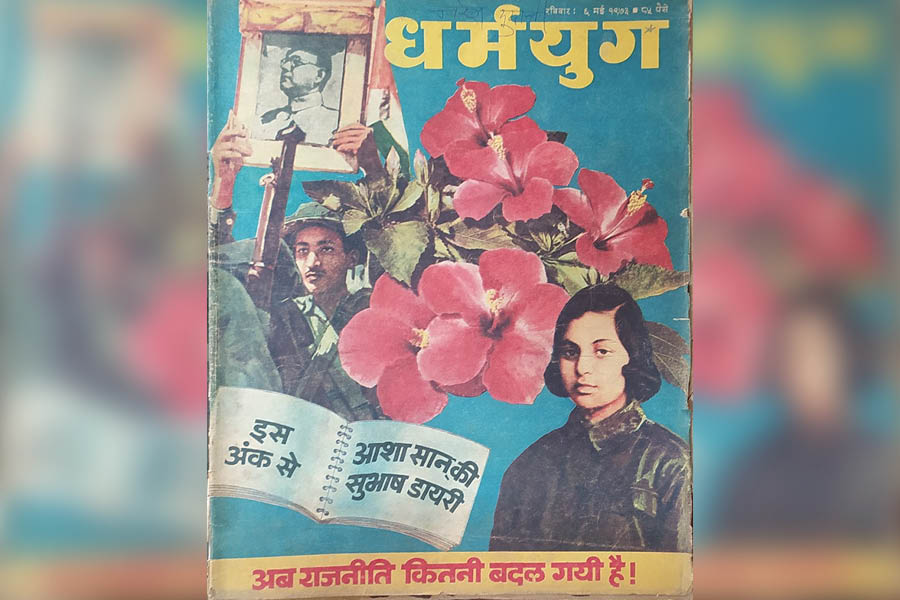

The War Diary of Asha-san has meandered through several avatars. Penned in Japanese during the Second World War by Asha-san, who was born in Kobe in 1928, it was translated by her into Hindi with help from her parents and also her Hindi professor when she returned to India. It was not easy going — writing on scraps of paper and frayed notebooks, but she would soldier on, meticulously documenting every emotion, adversity, challenge, meetings with great leaders, the interactions with the brave Japanese ready to sacrifice their lives, from 1943 to 1947. It was serialised in the popular Hindi pictorial weekly Dharmyug in 1973 and later compiled into a book titled Asha-san ki Subhas Diary, which was republished by Sanjay in 2011.

“I have been writing in my diary since my early childhood. Bombs may fall, typhoons may swirl, yet I cannot sleep without writing in my diary,” Asha-san says.

As we chat, Tanvi draws a parallel with Anne Frank’s Diary, written coincidentally around the same time in the early-1940s. Both young people, pouring their hearts out in different environments. Tanvi came across the book quite serendipitously in a bookshelf at home and it soon was to become a major project of translation for her, done during Covid, with two little brats in tow. Her grandmother-in-law’s story, she believes “seems to transcend time, space and language”.

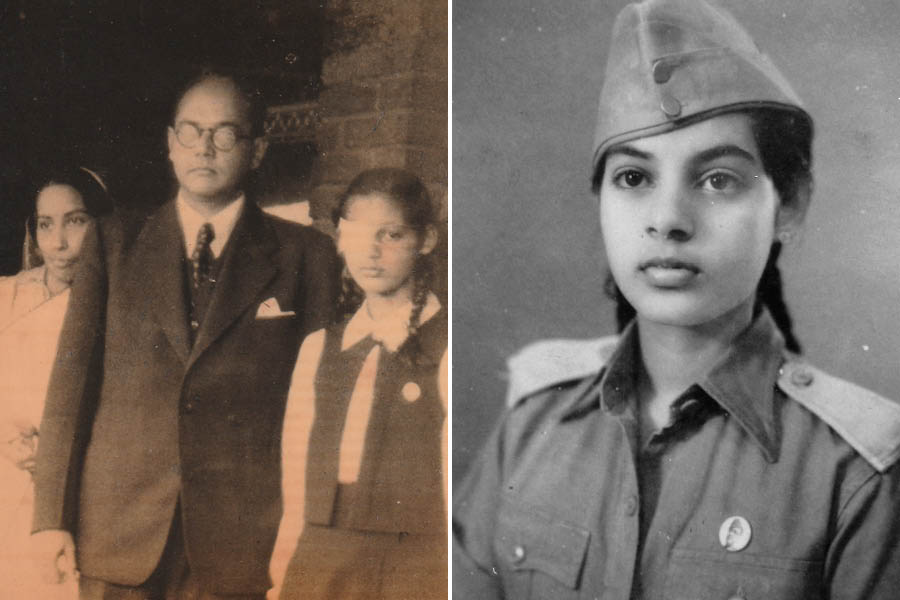

Lieutenant Sahay Choudhry with her family and (right) granddaughter-in-law Tanvi Srivastava

Tanvi talks of Asha-san’s love for nature, her Japanese ethos of perfection and etiquette — “an Indian girl growing up in Kobe and Tokyo, living a life steeped in Japanese culture, nationalism and ethos”.

This is a coming-of-age story of a 17-year-old who leaves her home and family to discover herself as a woman. Someone who never shied away from proudly saluting military officers as colleagues, a loud Jai Hind on her lips.

A word here about Asha-san’s parents. Anand Mohan Sahay and Sati Sen Sahay. The former was political adviser to Netaji when he arrived in Japan and went on to join the cabinet of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind as secretary and make Southeast Asia the main centre of his political activities. He had become a nationalist early on in life and had worked closely with Dr Rajendra Prasad, Mahatma Gandhi and later Rashbehari Bose in Japan. He helped set up several branches of the Indian Independence League across Asia.

Sanjay with Lieutenant Sahay Choudhry and his wife Ratna

Sati Sen Sahay was born in 1903. She was the niece of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das and participated in the Non-Cooperation Movement. She studied in Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan when nature, the arts and nationalism got deeply ingrained into her psyche. With an independent mindset, she played a crucial role in instilling patriotism in Asha from a young age.

Immediately after marriage, they set sail for Japan. Those were hard times, with food being meagre but the nationalistic spirit saw Sati Sen supporting Anand Sahay’s work and helping in bringing out a journal Voice of India in English and Japanese. She even designed currency notes of the Azad Hind government using her special skills acquired in Santiniketan. Sati was always the quiet warrior, whether in her beliefs or in the way she scrimped and saved to feed the family in hard times. Sati Sahay’s brave patriotism had her telling daughter Asha “... I have already handed over your father and uncle to Mother India. Now, you are no longer my daughter, but India’s daughter...”

They were to understand hunger and also in the same breath, stoicism, politeness, the ability to want to face danger and death, so many qualities that the Japanese had and which the Indians were to imbibe and ingest.

An old magazine reviews ‘Asha-san ki Subhas Diary’

Anand Mohan Sahay writes about daughter Asha: “During and before the war we resided in Japan, where we had an uncommon and unique opportunity to work for India’s Independence. Asha was also witness to these experiences. ...The war transformed Asha from being a delicate emotional girl to someone who was spirited, a girl who could face any fires, any storms.”

Asha-san writes ruefully: “In 1945, I was a newly commissioned lieutenant in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment of the INA. I was anxious and eager to reach the frontline as soon as possible. But it was not my fate to look the enemy in the eye. My rifle did not fire any bullets; my bayonet did not slash the arteries of any enemies. An entire organisation....built by patriots, fell apart in a matter of weeks. First with the atom bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then, the Japanese surrender. Then, the death of Netaji. My war ended before it started.

War is silence. War is doubt. War is not knowing.”

A young Asha at a felicitation ceremony

But coming back to India was a different knowing for Lieutenant Asha, after she had trained in Bangkok and was imprisoned after the Japanese surrender. She reunited with her father in 1946 and they returned to India along with Asha’s uncle Satyadev Sahay, who served as director of the Intelligence Bureau, INA. They toured India spreading the word of the efforts of the INA to liberate India.

However, no one in the family went for the Independence Day celebrations, for they felt the nation had split apart. At this point, Asha-san shared with us an anecdote that her mother had told her when the Indians in Kobe had decided to hoist the Tricolour from their homes on January 26, 1935. A daring act in those days. That morning Sati left home speedily, matchbox in hand, to see if every household had hoisted the Tricolour. All except three had done so and Sati went to their homes and burned down the Union Jack. When complaints went to the authorities, the Japanese interestingly said they do not punish patriots. And she was honoured and praised for her daring deed by both the Japanese and Indians in Kobe.

Settling into your own country with a new mindset takes courage and compassion. And some chutzpah. She married a doctor, and they settled into a new life, with their children, getting into the club circuit, doing a lot of social work. The comfort of the kimono had to give way to saris, the tatami abjured. But hey, nothing stopped the 80-year-old much later in life, as Tanvi recollects, when she first set eyes on her husband’s grandmother strutting into the dining room carrying a heavy saucepan full of rice and she was to be introduced to the art of sushi-making. She laid out the ingredients with precision: a bowl of salted water, three bamboo mats, several sheets of nori, finely sliced vegetables, a sharp knife and a mound of vinegared rice. Several rows of maki appeared before them.

Asha-san’s Japan connect continued apace. She became an interpreter for a Japanese temple in Gaya and made two trips to Japan, one of them in 2009 for the 90th anniversary of Showa Women’s University where she was the oldest alumna alive.

It was a Buddhist mindset and Japanese stoicism took her through in life. She lives in Patna now with her son Sanjay and daughter-in-law Ratna. Sanjay incidentally was my public relations counterpart when he worked with Tata Steel, moving on to being a consultant with Madeleine Albright’s firm and setting up an association for solar industries. He is involved with his wife’s teacher’s training centre in Sasaram. And Asha-san — still so agile of mind — is their pillar of strength. How she stole the show at a recent literary meet in Kolkata!

I end with a haiku I have composed on Asha-san:

She has huryu – style

May Asha San brave soldier

Have Banzai – long life