By the late years of Warren Hastings’ reign as governor general of Bengal (1773-85), Calcutta had started to change. It was on the way to take on a distinct character and emerge as the second most important city in the empire in the next half century. Boats coming from Europe deposited young prospectors on these shores — in search of fortune and prosperity. And soon, European beauties also started arriving as Calcutta became a favored destination for groom hunting. For the ones with means, life in Calcutta was good.

A letter home by a certain Mrs. Fay, a barrister's wife, who first arrived in Calcutta in 1780, gives a glimpse.... “We dine at 2 o’clock in the very heat of the day. A soup, a roast fowl, curry and rice, a mutton pie, a forequarter of lamb, a rice pudding, tarts, very good cheese, fresh churned butter, excellent Madeira (that is very expensive but the eatables are cheap). A whole sheep cost but Rs 2, a lamb Rs 1, six good fowls or duck ditto, 12 pounds of bread ditto, 2 pounds butter ditto, good cheese two months old sold at the enormous price of Rs 2 or 3 per pound, but now you may buy it at Rs 1 & 1/2. English claret sells at this time Rs 60 a dozen”. By the time good Mrs. Fey breathed her last (in 1815), Calcutta was getting soda water from messrs Schweppes.

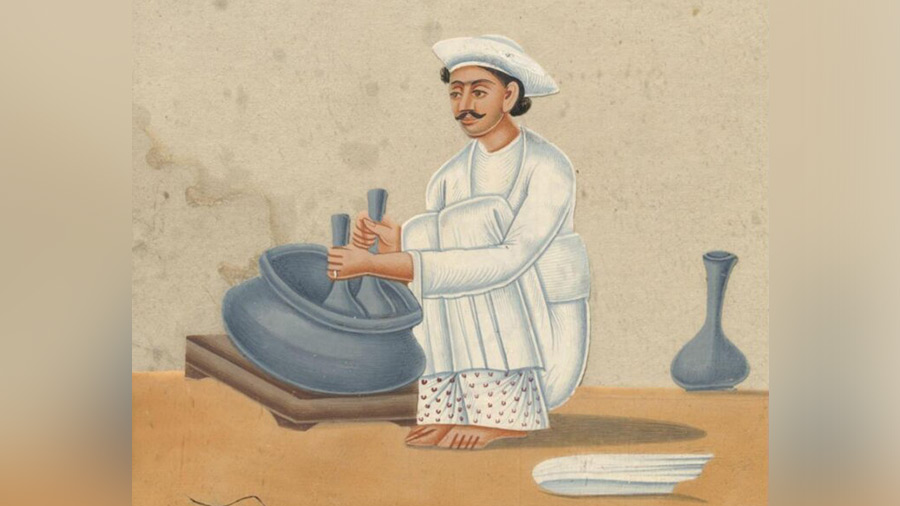

One thing though was generally missing and that was good quality ice to add to wines and spirits. The hot climes of Calcutta were hardly conducive to good quality ice making. Every family of means had a special servant, known as aub-dar, whose job was to produce something closely resembling ice, by moving an earthenware jar of water in a large receptacle containing saltpetre and water. On the days of parties in the household, the aub-dar was in prime demand, often working through the night. I haven’t been able to validate this but my hunch is the commonly used Bengali expression আব্দারি আবহাওয়া, used to describe the cool clime after a burst of shower on a hot day in Calcutta probably derived from the hard labours of the poor aub-dar.

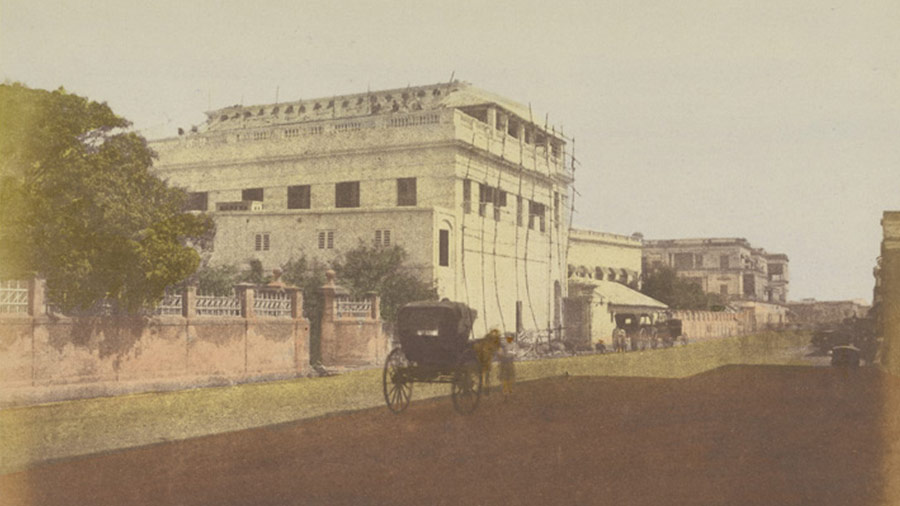

Calcutta Ice House Courtesy British-Library

By the early years of the 19th century, commercial ice production had started in Chinsurah, 40km from Calcutta. But this was low quality ice — filthy, more like slush, made by freezing the Hooghly water in shallow pits every winter. It could be used industrially but couldn't be added to the tipple. But the scene was to witness an amazing change very soon.

Enter Frederic Tudor, an American merchant from Boston. Tudor realised that there lay great prospect in the export of ice to distant shores. The cool climate and abundant lakes of Massachusetts provided ample natural supplies of ice. And with technological advances rendering faster steamboats for marine travel, the plan wasn’t as ludicrous as it sounded.

After burning his hands a few times, by 1833, Tudor had a decent business running, exporting ice to Europe and the Caribbean. The same year, he was approached by another merchant, Samuel Austin, who was facing a different predicament. Austin was trading with India and while Indian silk and spices had great demand in America, he had little to take the other way round. Fur and dried fish, top American exports of the time, had hardly any takers in tropical India. The ships were filled with sand to provide ballast on the voyage. Tudor suggested Austin fill up the ship with ice blocks instead of sand.

Frederic Tudor aka the 'Ice King' Wikimedia-Commons

In the sweltering May of 1833, Frederic Tudor dispatched 180 tonnes of ice blocks in the vessel. They decided to sail to Calcutta — the most important city in British India of the time. The voyage was to take four months. By the time Tuscany berthed in the Hooghly, nearly 40 per cent of the cargo had melted. Yet 100 tonnes remained intact and as the ice blocks were unloaded, it was a fascinating spectacle for Calcutta’s European residents, many of whom had thronged to the docks to witness this scene.

Calcutta’s European gentry went crazy. Now they could have iced drinks, chilled wine, cool beer and cold desserts, and just the delight of some relief from the heat. Gavin Weightman, in his book The Frozen Water Trade, writes that in no time “a committee was formed to collect subscriptions to build an ice-house — not a wooden American structure, but a grand stone edifice more fitting to the ‘city of palaces…’”

Aub-dar Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The ice house came up in Bankshall Street and was an object of pride for British Calcutta. Very soon, Bombay and Madras also followed suit as Tudor’s ice laden ships became the object of much affection. The enterprising American soon realised that his profits could improve more as he started exporting apples and butter, products that were well preserved in the ice. From 100 tonnes in the first shipment of 1833, import of ice went up to 3,000 tonnes by 1847. Over the period of 20 years, Tudor made a profit of US $220,000 from Calcutta alone and came to be known as the “Ice King”.

Tudor’s death in 1864 and development of new ice manufacturing processes started the decline of the American ice trade in Calcutta. With the establishment of the Bengal Ice Company in 1878 and Crystal Ice Company shortly thereafter, good quality ice was locally available. The Calcutta Ice Company, once an object of pride, was demolished in 1882. The one in Bombay survived as a warehouse till 1920, when it was also brought down. Only the one in Madras has survived till date and has been renamed as Vivekanandar Illam, a museum in honor of Swami Vivekananda, who is believed to have stayed there in 1897.