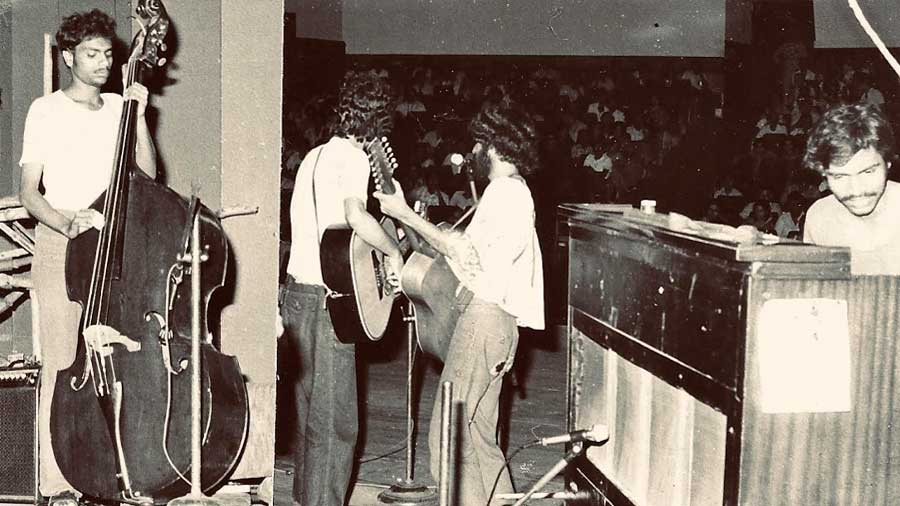

Sometime in the 1980s, a bunch of boys, most of them in their early twenties, found themselves on stage at the Calcutta International Jazz Festival. They used to be called Mohiner Ghoraguli, a band put together by Gautam Chattopadhyay who was audacious enough to write rock songs in Bangla. The fellow playing bass for them at the time was Biswanath Chattopadhyay, or Bishu, who ended up moving to the US soon after (1983). Now, he has two albums to his credit.

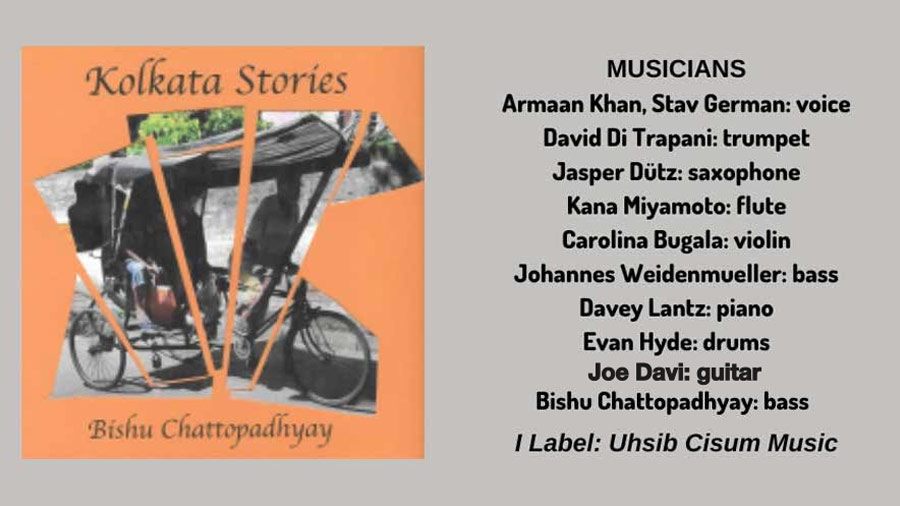

Bishu’s latest, Kolkata Stories, a jazz album, has its roots in the 2020 nationwide lockdown at the onset of the pandemic. He was in Kolkata then, suddenly finding himself locked in, the unpleasant experience, aggravated by Cyclone Amphan. Nevertheless, he channelled his thoughts to write 20 tunes, 10 of which made it to the album recorded in New York the following year.

Kolkata Stories is a lovely collection, a palette of conventional sounds within the contours of free-flowing, straight-ahead jazz. It doesn’t seek to overwhelm you at first listen. Rather the ideas suck you in gently. Mellow in general, but often punctuated by flourishes of the sax and trumpet, a searing violin here or a flute interlude there. There is an honest search for a sense of order. At times it’s there. At other times, it may seem to head nowhere. Much like our beloved city. Sad, tired even. At times exasperating. But joyous at heart.

Bishu’s double bass introduces the first track, Midnight Rickshaw with Reni, the piano unveils a tune amid gentle brush strokes on the drums in A Sonnet for Ranjon, the second track. But we get stuck on Ustad Rashid Khan’s Tree that begins with a seductive flourish of the sax and trumpet as the vocalist joins in. Beautiful. Bishu has often spoken of his music as being at the intersection of jazz and Indian music but takes care not to cling to the usual tropes of such a combination. The confluence is in the ideas and the playing. The only overt reference to the city, other than the titles, comes in Bengali Night with No Moon — 'Dark night is the tune/ Don’t sell me the moon/ Doctors come and go…'

“Kolkata is a place of song, right,” he tells me from his home in New York City, and delves into his music, life as it used to be in Kolkata during the days with Moni da and Mohiner Ghoraguli, his own tryst with the tabla and cello before getting hooked to the bass, courtesy the jazz fest where they ended up sharing stage with Mingus Dynasty, a powerhouse ensemble put together with the legendary bassist and composer Charles Mingus’s sidemen to keep his legacy alive, and the many music teachers he has had, among them the great Ron Carter.

Bishu was 25 when he moved to the US. In San Francisco, while working as an economist for 25 years, he established two bands, Bengal and Beyond, Time Is Now Not Money. Now in his 60s, he leads two bands, BC All Stars, BCjazzNow in New York City, and is happy to report that life as a full-time musician for about a decade now has been largely fulfilling. He speaks softly, with a slightly raspy voice, a few notches louder than Miles Davis’s characteristic whisper. Our discussion on Kolkata Stories veered around the days of hiring pianos, Elliot Road rehearsals, running away from a classical music concert in Kolkata, work-life balance in the US and more. Excerpts:

I must say that Kolkata Stories is a lovely album — spontaneous, intimate, at times confusing, but heart-warming.

Thank you. Yeah, I have got a lot of good feedback. Unlike my earlier album Harlem Meets Hooghly, I had a different take on this. Basically, I was stuck in Kolkata for three months. That’s when the creativity was happening.

I found the music all-encompassing, offering space to all the musicians in the band in equal measure. The double bass, piano and the drums providing the cushion on which ideas are allowed to flow.

Right. That was the purpose. Even my deciding to continue to play bass is because it is in the background. It holds it all together. And I always loved that. It's like how you would describe a leader who is not continuously reminding the group that ‘I'm a leader’. That's where the good work shows up. I see things together. So, I am always attracted to that aspect of the bass. The album is a kind of extension of that.

Bishu Chattopadhyay (on double bass) with his band at Nomad, New York City, 2019 Courtesy: Mamuka Berika

So, you got caught off guard — like the rest of the nation — with the lockdown in 2020? It was, I am guessing, an unpleasant experience. So how did you channel those emotions into music?

Well, it's a long story. Originally, I was there for 10 days. I was staying at an Airbnb, which was a penthouse with no kitchen, no air-conditioning, nothing. It was very hot. But it was okay. In Kolkata who needs a kitchen? You are always with family and outside. Eventually, I moved in with my family when things were really out of control. Because there were all kinds of apprehensions about the pandemic — ‘Look, he’s from the West, has he got tested? I have diabetes, so, should I go and meet him?’ And we couldn’t go out. I had even heard of threats of being arrested. I was more afraid of getting Covid from that. So that's when all those emotions started. And the songs started to come. It was the best way to get all my feelings out.

As the title makes it clear, this is an album of stories. Tell us some. For instance, what’s with Ustad Rashid Khan’s Tree, clearly one of the standouts of the album?

Yes (laughs). I was staying at my sister's place in Naktala, which is next to Rashid Khan's home which has a big compound. He had this tall — like three storeys tall — Radhachura tree which was beautiful. My sister was always interested in botany so she would always show me these things. Then Cyclone Amphan happened. Amazingly, this gigantic tree fell to the ground. I couldn’t believe that this tall tree (could fall) … So, that inspired the tune. And then I thought that it should be sung. That's how it all happened. Similarly, Dusts of Fear is also about witnessing the devastation of Amphan in Kolkata.

Bengali Night with No Moon is perhaps the only track which has an overt reference to Kolkata. And it’s also a song which says, ‘Wish I could go back and play my song’. Is that a thought that comes to your mind often when you think about Kolkata?

Absolutely. What happened is that I sent my singer the music. I just wanted her (Stav German) to vocalise as she had done in the past. Either she didn't read my emails completely, or whatever, but she said, ‘Oh Bishu, this is great. Where are the lyrics?’ And I said, ‘Oh my God, I don't have lyrics’. So, I wrote it literally in a week, every night before going to bed I'd stab at two lines. So that's how the lyrics came. But I haven’t been planning on any lyrics since Mohiner Ghoraguli days. The song talks about being stuck in Kolkata and then doctors and all that and then going back to play music. Normally, Kolkata is a place for song, right? I go there, get together with people and play. But this was a very strange space. So, ‘wish I could go back and play my song’ was to express that.

Now that you can look back, what would you say is the key behind Mohiner Ghoraguli leaving such an indelible mark on the music of Kolkata?

We made some people unhappy. We didn't know that people would dislike us in that way. More that happened the more we believed that wow, maybe we're doing something that’s worth doing. So, there was this rage, or something (which led us to) believing in ourselves.

Moni da, I have now learnt, would joke that Mohin’s first album had foreign funding, an allusion to last-minute borrowings from a Kabuliwala.

When our first album was released, we went door to door to sell it. Some would ask if we were a new theatre group, while others would dismiss us saying they didn’t have a record player. There were people who were buying (the album) too. But the Bengali culture of white — white clothes, white mats, etc — was very oppressive and foreboding. I remember thinking ‘God this is our culture, and we can’t get in’. Because it is so established. You know, the status quo of music. Honestly, we did not think much. But we knew we were doing something different.

But it wasn’t all gloom. I remember walking with a friend, in maybe Behala or Jadavpur, when for the first time we heard our song being played… the music was coming from an upstairs room. Wow, it was such a feeling.

Gautam Chattopadhyay comes first when you talk about your music teachers. What was he like?

First, he was a terrific musician. When he was young, he was playing tabla. And he was so much in demand. And if he just stayed with tabla, he’d be the tabla man. But he had this feeling — and rightly so — that tabla players in those days weren’t respected. You come on the stage, so-and-so is on sitar so-and-so is on vocals and then there's the tabla player. Even on records, the tabla player was hardly ever credited. So, he didn't like that and switched. He was very patient to teach. I noticed that if he sees you are good at a particular thing, he will just make that a resource. And then, all of a sudden, he’ll use it in a particular song. He found you. He had a vast kind of openness to any kind of music — Nepali gaan, Santhali gaan. And he had tremendous memory. He would come back, listening to a song twice and remember the lyrics. For me, I can remember the melody. But the lyrics? So that was very impressive. He was a great organiser. I remember being so stressed with school and college and all the rest of the things going on in our life. And it was not as if all the music was on YouTube or something. But he always wanted us to continue. He would just say that this August 15 we are playing at Star Theatre! What? And then we’d start rehearsing, and then it happened. So, he was a great organiser in that way.

Bishu Chattopadhyay (on double bass) with Mohiner Ghoraguli at Rabindra Sadan, Kolkata, 1979 (Photograph by Tushar Kanti Dutta in the book, Mohiner Ghoragulir Gaan, published by Chhapakhanar Bhoot, March 2021) Courtesy Bishu Chattopadhyay

You started with the tabla too? How did the double bass happen? How did jazz happen?

Those days I was working at Alliance Francaise as a translator/ interpreter. And my friend Abraham Mazumdar, whom I met through Boy Scout, opened up the whole world of classical music to me. He took me to Oxford Mission, founded by Father Matheison who ran this orphanage with a focus on music. Then, I met Mridul Roy, who was Abraham’s friend, and he became my cello teacher. By then I was playing tabla and a bit of guitar.

Then, sometime in the 1980s the Calcutta International Jazz Festival happened when Satyajit Raychaudhuri of Jazz India approached us to play. So, it was like wow. I mean, we're doing folk rock improvisation, not really jazz. But we took on that challenge. And it was logical that Bishu, who was playing cello, would take up the bass. I think we rented it from Braganza’s or Abraham got it from Oxford Mission for six months. We didn’t even have our own piano or rehearsal space. We would rent this place, I think from Tony Menezes or one of those people that Abraham knew had a piano, on Elliot Road to practise.

How did you all start to improvise?

I remember my teacher Mridul Roy took me to play (one of the) Brandenburg Concertos at the Calcutta School of Music. And I was like at the last row with cello and Abraham was concert master or something. And after a few rehearsals, I ran away (laughs). I told Mridul that this was not what I wanted to do. But he said, ‘it's very good for your reading’ and all that. Which is true. But I didn't end up playing that concert because I had already taken to the bass. We were already improvising. Which was a big thing. Like when we would jam, somebody would sing one of Mohiner Ghoraguli songs. And then the song would end, but we didn't stop as everybody's taking turns and doing things. We didn’t know what we were doing, but we were expressing ourselves. So all of that and the jazz fest helped.

… learning to play the cello definitely helped too. Because, I remember, Mingus Dynasty were there on the stage with us. [Mingus Dynasty was the first band Sue Mingus put together after Charles Mingus’s death in 1979 with his own sidemen to honour the life and work of the composer and double bassist] They used my bass, but I used their strings. It was like a scary thought. We were little kids. And so, this experience gave us a lot of confidence.

And after that?

So we just continued. In Kolkata, Abraham and I, and there was a guy named Kankar, we did a trio — violin, banjo and bass. And we did some shows. This was when Mohiner Ghoraguli was getting scattered. I know Monida was very busy with his film. He even came to see one of our shows at Alliance. Kishore Chatterjee wrote about us. So, we knew we had some people who loved us and then, I said, okay, bass is my thing. Cello is a beautiful instrument, but bass offered more freedom, especially during jazz. And then I came to the US and just stuck with that.

You also list Ron Carter as one of your teachers. I mean, he's a legend. How did that connection happen?

I knew a percussionist who hooked us up. Ron turned out to be very fussy. He didn’t let me play his bass. I had to get my own. And I knew so many of his albums, so I thought he is going to quiz me. But someone like Ron, they're so busy touring. But yes, (he’s) a wonderful inspiration.

I could tell you a story connected to the album. Ron called to give me some feedback on the album, particularly the piece titled ‘Saraswati | Two Basses’. I do not remember everything he said. He did mention that he liked the microtonal arco use in the beginning of the piece, which reminded him of the possibilities of incorporating elements of traditional Indian music. As he was talking, I said at one point, ‘Maestro, I wish I had recorded this great conversation.” But I realised that if I had recorded the conversation, that would have stolen its spirited spontaneity. So I told him it was just as well that our conversation was not recorded. I mentioned the Buddhist tradition of sand Mandala painting, where hours are spent to create this beautiful art, only to see it destroyed soon thereafter, to remind us of impermanence. Ron replied, ‘I do not know much about Buddhism but after studio recording sessions musicians often ask me to come to the playback room to listen to what we have done, and I tell them that I do not need to hear it again. I listened to the piece when we played.’

While listening to Kolkata Stories I was reminded of Avishai Cohen and his trio. The piano, bass and drums are such a pure combination.

Thank you. Avishai Cohen is also one of my favourite composers. He’s done some amazing things. I know one of his pianists, Shai Maestro. He lives in Brooklyn.

Who else do you listen to?

I have originally listened to recordings of Miles Davis, Keith Jarret and later heard them live in the US. My early friends (vinyls and cassettes) in Kolkata are a bit random. For instance, Charles Mingus – The Clown, John Coltrane – My Favorite Things, Nikhil Banerjee – Afternoon Ragas, Dave Brubeck Quartet – Jazz Impressions of Eurasia, Egberto Gismonti – Dança Das Cabaças and Weather Report - Heavy Weather.

Are you a full-time musician now? Or are you still working elsewhere?

No, I don't work for the CIA (laughs). I have been doing only music almost for the last 10 years. But there was a time I had to have a day job and continue playing on weekends. It was good, but then I missed out many opportunities. Once I took off from work for a few months to play on a cruise ship. My boss wasn’t happy at all. It was always a struggle… And I also appreciated the money I needed to pay rent, take care of family, etc. Then at some point I asked myself if money is more important or what my heart wants. And this is also something I learned from Monida. And people would come and ask for ‘jhin chaak’ music. But he would turn them down even though he could make money. I was young then, but that stayed with me.

‘Jhin chaak’ and Monida are good notes to end on. Thank you for talking to us.

Thank you. It was good to connect.