The first time I read the foreword to Poor Economics for Kids, I could not hold back my tears. Abhijit Banerjee, who wrote the foreword, says: “Too much of the discussion in the world about the poor is wrong-headed, because it ignores just how hard it is to be poor and therefore blames them for the problems of their own lives.” Being a scholar of English literature who taught diasporic and world literature at the University of Toronto, and now at Loreto College, I felt the two Nobel Prize awardees had delivered a sledgehammer. Immediately, I thought of the beautiful but emaciated Little Match Girl (a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen) who sold matchsticks and died on Christmas Eve, frozen outside an opulent home of a merchant whose table was groaning with a roast goose dinner.

This new and compassionate way of looking at the incomprehensible and unsolvable problems of poverty and deprivation helped me transform the literary and the historical theory that I mulled over for decades into praxis. That is why I am blown away by how effectively we can use this book, Poor Economics for Kids, to help us look at poverty right across geographies and histories to reconfigure why the poor as represented from Hardy to Dickens, Brecht to Satyajit Ray, Kipling’s Kim to Arundhati Roy to Ngugi to Malouf to Elif Shafak, find a more inclusive, more kind and more pragmatic way to change our perception of the poor.

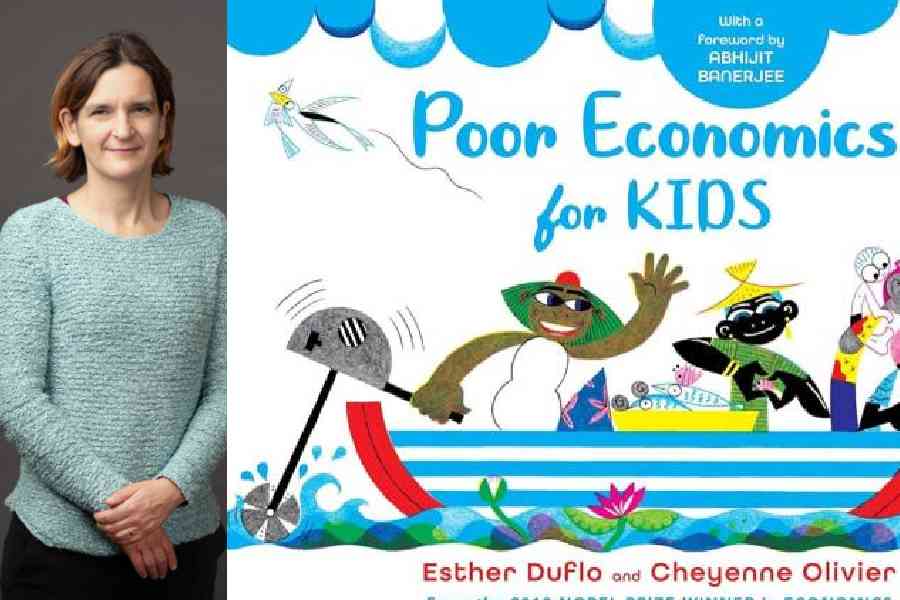

There are 10 endearing stories in this simply written book that make accessible the complex issues of poverty and inequitable distribution of wealth. Perhaps its greatest contribution is the non-judgemental way the writer, Esther Duflo, and illustrator collaborate in presenting the cultural, social and everyday struggles of millions of young folk who lack opportunities to fulfil their potential. Modest and unpretentious, written with effortless charm, this is a unique cache of stories that will arrest the interest and attention of any young reader who is interested in why there are children who have no books, cannot ride to school in their bicycles nor bring a tiffin box that has some food to sustain them through the day. Written in a friendly and felicitous style by economist and Nobel laureate Esther Duflo, and evocatively illustrated by Cheyenne Olivier, the stories bring the serious disparities of people all over the planet to the not-so-happy reality of the human condition we encounter as the privileged, educated minority in a world that finds it convenient to turn away from the unfortunate who cannot break away from the pangs of an empty stomach or the helplessness of being unable to tend to their sick old patents.

These stories are about Nilou and her friends, a group of children and teens, and the adults who live with them. However, the collection speaks to children across geographies and histories, as the introduction so simply states. These children live in a village, one which could be in India or Kenya or Vietnam or elsewhere, and we see them deal with some ordinary and not-so-ordinary challenges.

Says Esther Duflo, “I hope you enjoy getting to know Nilou, Imai, Najy, and Neso, and all their friends as much as I enjoyed meeting the many real children who have inspired me to create these ones. I hope, too, that they answer some of your questions, and lead you to ask many new ones. Like Nilou and her friends, never stop dreaming and being curious!”

A t2 chat with Esther Duflo, a Nobel Prize for Economics co-awardee with her husband Abhijit Banerjee, and Cheyenne Olivier, the illustrator for her new book Poor Economics for Kids, as they ploughed the skies, on their way to launch the unique new book in India. Calcutta await the event on Monday, July 8 at the ICCR.

Your compassion is perhaps the most unique quality that drives the engine of this project. Did you clearly want to change the way poverty is presented to the impressionable mind of a child?

Esther: We wanted to change the way that poverty is presented. Period. This was already the project of poor economics: to try to go past the stereotypes and caricatures. When we published the book (Poor Economics) we were struck by the fact that what most changed people’s views were the anecdotes from real lives we had peppered the book with. That’s when we thought a children’s book made of stories would work well. Because young readers are open-minded, and also because readers of all ages are touched by stories.

When did you and Dr Abhijit Banerjee find that something radical had to be done so that children from all strata of society would stop blaming their “abjectly poor” brothers, sisters, and their parents for being poor, “dirty”, living in “unhygienic, appalling conditions”? Was it a single mind-changing incident, or was it an organic thought process?

Esther: We remember our own misconceptions as children. We were well-intentioned, but had all sorts of wrong ideas of who the poor were and how they really lived. I remember both the lasting impression made by books I read as a child and also the fact that these books were not very good because they conveyed those stereotypes.

So I thought it would be important to write for kids.

We generally think of Keynesian economics, behavioural economics, micro and macro economics and often the students in the arts faculties are apprehensive of quantitative components. However, as “randomistas”, you have made economics in the Postcolonial context accessible and exciting. Can you explain how you made Poor Economics for Kids so relatable? In your fieldwork, what instances or aha moments do you recall in Ghana or in West Bengal that brought you to your knees?

Esther: Thank you for calling it relatable! I think that with 10 stories, the characters have plenty of space to get developed, as full and complete people. So you see how some of their problems are different, and some are very much the same. For example, Nilou daydreams in school, the friends argue, invent some challenges… there is no aha moment, it is the natural flow of life.

In the first few pages of the book you state quite lucidly: “In effect, people all too often assume that the poor must be losers who don’t have it in them to help themselves.” This is exactly the belief system that has been ingrained into the children who repeat the cycles of poverty as well as the privileged. How would you explain to your graduate students in the US the concept of appropriation and hegemonistic control in patriarchal or masculinist cultures where underprivileged women are made to believe that it is the right of the wealthy man to have unfettered access to the poor body?

Esther: Interestingly, we would say our graduate students are, as usual, ahead of us on this. Several are working precisely on that: for example, how women can be shown that they have self-efficacy, and how to exercise it; what kinds of jobs can be offered to women that are easier for them to accept; what are the consequences of the male focus on ‘purity’.

The concept of women’s empowerment and fiscal security and their intractable bond with education is still a dream to many millions of women. How do you envisage a method to work in this very challenging area? In the last three years, several memoirs, including Manish Gaekwad’s The Last Courtesan of Bowbazar, have unveiled the unchecked growth of trafficking in women by male members of their own families and how women’s self-reliancy has freed them from such slavery. What would you suggest as motivating factors to give young women a better, more financially mobile existence?

Esther: In the book, there are many strong female characters, both among the kids and among the adults. But we are also not hiding the constraints that women and girls are still facing. When I saw that the ICA agreed to their chief guest’s request not to have women sitting in the front row, I thought that much progress still remains to be made. The last book is all about the seemingly benign paternalism found both in families and communities, and which prevents women and girls to do what they want in the name of their own good.

The illustrations are very poignant and add value to the text. They bring an alluring component of oral culture. I loved Ms Cheyenne’s bright and beautiful character portraits. For instance, the courage and character of Najy and his love for Bulbul make him a new-age man. What was it like to collaborate between wordsmiths and artists?

Cheyenne: For the three of us (Esther, me and the French publisher who was very involved in the project), the characters were very much alive, they were combinations of various people we know and we felt that for them to be compelling, they had to have a life of their own that couldn’t be filled only with the difficulties they faced. We constantly reworked the text and the image together but Esther gave me a huge freedom to populate it with my own interests and add many useless details that eventually make the flesh of the stories.

Cheyenne, the graphic novel is such a favourite genre now. How did you think of enlivening the rich bank of stories that Duflo writes about? What were the challenges of working together?

Cheyenne: Since Esther told me from the beginning that the stories couldn’t be placed in a specific country, I had to imagine the entire visual world of Nilou. For this, I relied on the existing visuals in economics and more specifically, the S and L curves presented in Poor Economics. They form the ground of all the stories, evoking the highs and lows of the characters. I also used a limited set of geometrical shapes to compose everything, from houses to characters to trees, to echo economics as the art of re-organising a finite set or resources. The challenge for me was to rethink my own visual prejudices about the poor, and to create such a complex universe over 10 books.

While writing Poor Economics for Kids, how did your roles as parents to your own children help you understand these academic and esoteric issues of the global concept of poor economics?

Esther: We started working on the books when our children were eight and six. They were the first readers of the books and in particular, our eight-year-old daughter was a keen editor. She was able to point out whenever a plot point or a character action didn’t ring true to her.

What can the randomista kind of economics do to transform the terrorising realities to improve our world?

The convictions that undergirds the randomista movement, as you call it, is that poverty is not one giant unsolvable problem. It’s thousands of specific problems that can be addressed one by one. This is also what we try to show in the many stories in this book: there are different situations, and also many different actors that are all playing their parts. Their collective effort is what makes life a little better for everyone.

There still lies a mammoth chasm between those who drive bullock carts and those who drive BMWs to work. At 600 million Indians living at ₹50 a day, what hope do our poor children have to break on through to the other side?

Yes, there is. And yet through all these books we want to demonstrate that we are all a shard of humanity — poverty may seem insurmountable because it creates its own traps. But it is possible, and necessary, to find the right levers. The story of Kombu, the fake witch, which gets out of extreme poverty thanks to the graduation program, is based on a real program we have evaluated, which was invented by BRAC and is now implemented all over the world, including in India where it has reached 200,000 families through a government programme. In all of the subsequent books, Kombu is a wise person who contributes a lot to life in the village. Her potential is finally realised.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College