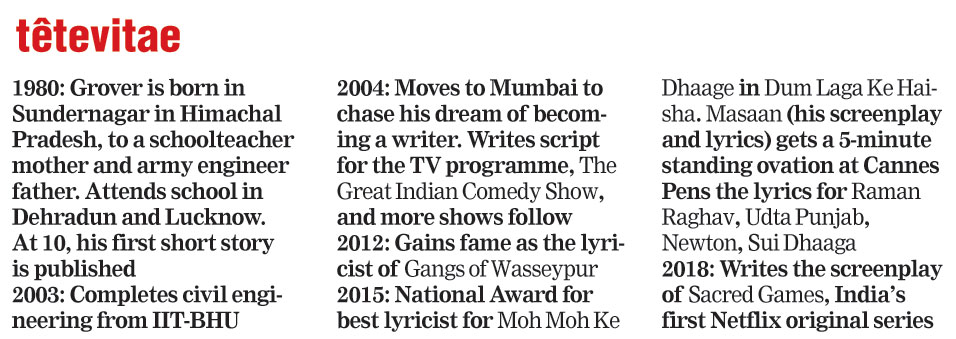

The day I meet Varun Grover, almost everyone in the media is agog with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the Kedarnath shrine and the visuals circulating. It is as though a new film has been released, a film with just one actor, about one actor. Grover, a stand-up comedian, screenwriter and poet, is in Calcutta for a show. His is a familiar face on television and social media, being funny in a casual, tentative manner. He is also behind the screenplay of the Netflix series Sacred Games, the soulful lyrics of Sonchiriya, Udta Punjab, Masaan and a dozen other Hindi films.

I am to ride with Grover to the airport if I want to know why the comic scene is roaring like it is. I meet him late in the afternoon outside a restaurant in Gariahat that serves Bengali food. The lanky 39-year-old appears to be in a happy state of being, speaking fondly of the doi maachh, shorshey maachh and mishti doi he has just devoured. However, for the next hour and a half — not including a brief stopover to pick up some baked rosogolla — he is dead serious.

Comedy as an art form is still an unorganised activity in India. Yet, there seems to be a surge in open-mics and stand-up comic performances with a large chunk feeding off the current political scenario, especially government heads, policies and media representations. Is there any other head of state who has been a subject of so much satire, I ask Grover referring to the Kedarnath brouhaha. “Well, it was they (the BJP) who started it all, by ridiculing the leader of the Opposition as Pappu and discrediting him as a fool,” he replies.

But how does that explain the growing number of comics? “The political has become everyday. Our Prime Minister is at the centre of news always; he gets more coverage than any sports star or Bollywood hero. Therefore, people are more aware now, even if they are aware of only one kind of politics, one narrative.” And that, he says, is what makes for fertile ground — a good set-up that everyone is familiar with. “It’s just right for anti-establishment comedy. But if I talk about say the DMK, not everyone will understand.”

Not very long ago, stand-up comedians mostly dug into the socio-cultural realm, rarely venturing into the political. Grover gives the example of the Mumbai-based EIC or East India Comedy, a group of humour writers, script writers and comedians, that shot to fame with the “demonetisation song” post November 8, 2016. “They could take that step forward because this guy [Modi] has made it easy. It’s a good piece of work; it registered 10-15 million views,” he adds.

In that sense then, the entire political class of today would be a willing subject. “Of course,” says he. “We critique all politicians who are in power, whenever there’s a talking point. A few days ago we spoke about Rahul Gandhi’s soft Hindutva approach when he professed to being a Shiv bhakt, etc. Then there was Arvind Kejriwal and the whole saga of first fighting the Congress and then seeking their support. We also called out the Aam Aadmi Party when it went silent on the issue of the JNU sedition charges. In the given circumstances, sometimes it may look like it is party-oriented but actually it is not.”

The Telegraph

By this time it has begun to drizzle and the roads in this part of the city are empty — it is polling day, the last one. Grover is an old fan of Calcutta, not least because “the city has a sense of humour”. I remind him that only a few days ago, a young BJP party worker was jailed because of a social media meme ridiculing the chief minister, Mamata Banerjee. “Is she paranoid?” he asks, rhetorically. Indeed, there’s an entire list of cartoonists and other humourists being put behind bars, be it Bengal or elsewhere. Stand-up comedians too function on tricky ground — what is comedy for one could be effrontery for another.

Did he face anything of the sort? “Not really,” he replies, “except for one minor incident. This was at a college and my topic was sex education. A professor sitting there felt it was unpalatable… beech mein rok diya.”

Grover’s performances are mostly held in auditoriums and conclaves, where there is resistance but of a different kind. There are, of course, underlying currents. He says, “In industry conclaves, more people are against our views.” At other times, he goes on, the reactions are more obvious. The comic artist says with a chuckle, “At media festivals… I can see that half the people are laughing and half not. Sometimes people don’t want to laugh because it’s wrong to laugh at their own establishment. What if a colleague sees them laughing at a Modi joke and complains to the boss?”

We arrive at the sweet shop. Grover asks for his baked rosogolla to be packed well, all the while eyeing the tempting yellowish mango sandesh displayed on the counter-top. “They make very good chhana pora too,” I suggest. He quips, “My cat is called Chhana Pora.”

Back in the car, I ask him if there are subjects that aren’t a smooth ride, topics that he hasn’t been able to crack yet. “There are two things that are works-in-progress,” he says, slowly. “First, the idea of nationalism, which is a most sensitive topic now, more so than the cow…”

The other complicated area, he says, is caste. I don’t quite get it. He explains, “Comedy is when you hit back, in a witty manner, from the position of being an oppressed at the oppressor. That’s why it is easy to create anti-establishment comedy — you retaliate by punching upwards. But in the case of caste, do I have the mandate to make it sound funny?”

What about fundamentalism, has he addressed Islamic fundamentalism in his acts? He replies, “Sanjay has done it; he has attacked dogmas such as triple talaq, the idea of qurbani.” Sanjay Rajoura is Grover’s associate, and along with Indian Ocean singer Rahul Ram, the three constitute Aisi Taisi Democracy, a political satire group.

It is often said that the failure of the liberal classes in India has a lot to do with their failure to critique Islamic fundamentalism, I say tentatively. Grover seems to agree. He says, “But ideally, that kind of criticism must come from Muslims — Muslim liberals have the first right to talk about Islamic fundamentalism.”

He goes on to explain that in a country such as ours, religion becomes an indelible part of one’s identity however much one tries to embrace atheism. “In that sense, I have a bigger understanding of the dynamics of my religion, and I am in the right position to attack certain aspects of it. But if there’s a Muslim comic talking about Islamic fundamentalism, I’d definitely go out and promote that person,” he adds emphatically.

Perhaps in the West all of this is much easier, no? Grover says, “British comedian Imran Yusuf is fantastic and so is Shazia Mirza, also London-based. We have Azeem Banatwala here, who does talk about it. More voices from the community should come forward and take the space because it is right there for the taking.”

It is a tricky area, and therefore another “work-in-progress”, he mulls. “Ideally, we should be able to talk about everything, whatever affects us — the ‘us’ of this country; the idea of India includes everybody. And one should be able to speak the unspeakable,” he adds.

It’s been some weeks since the interview, some weeks past May 23 too, and I make a brief call to say hello and ask how the verdict has made for comic fodder. It turns out Grover has been busy with the post-production vitals of Sacred Games, Season II.

“But the way forward is the failure of liberalism, and that again is a huge space,” he says, laughing heartily all the way.