There was a fellow near our place. Bhaba Pagla. One of those cranky blokes, you know. He used to hum an indigenous tune to which the kids used to laugh,” said Anuradha Gupta, Pancham’s maternal aunt (cousin of Meera Deb Burman, Pancham’s mother) to us one June afternoon in 2014. We were at her place in Laboni in Salt Lake, Calcutta. We felt like asking her to hum the tune. But resisted. Stopping the flow could be counter-productive for a lady who was touching eighty. She was fragile and not in the best health.

She continued. “Pancham later worked on the tune and created Sar jo tera chakraye. It served as his entry as an assistant to his father in Pyaasa. He travelled to Bombay. A bit of Calcutta died with him that day.”

***

R.D. Burman — affectionately Pancham — had moved to Bombay in the fall of 1955. Contrary to popular belief, his journey was not of his own free will. Composer-singer Dipankar Chattopadhyay recounted: “You see, Pancham had become quite a renegade. He hated studying. He also did not want to shift to Bombay; a regimented life was something he was not interested in. S.D. Burman almost tricked his son to come down to Bombay, saying that Ali Akbar Khan was doing most of his work there and it would help Pancham in pursuing his musical education. He was learning the sarod then.”

Did the sarod really interest Pancham? Sarod maestro Aashish Khan Debsharma, Ali Akbar’s son, said, “Not that Pancham was a very serious student. But he had a wonderful musical mind. And he used to listen a lot.” Kersi Lord, ace musician and a regular with the Burmans, added to this, “Pancham used to listen to all genres apart from Western classical music. He did not have the patience for it.”

Singer Subir Sen cast some more light on the listening patterns of Pancham. “I had come to Bombay at the insistence of Guru Dutt, and used to meet composers in anticipation of work. It was on one such occasion that I met S.D. Burman. In the process, I saw his son, dressed in a baniyan and shorts, dancing to Western music. And his father was cursing himself — Why did I teach him the sarod? Why?”

Listening to Western records had become a habit with Pancham since the time he was a child. Sachin Ganguly, S.D. Burman’s Calcutta-based secretary, used to take him to the shops — Wellington, Free School Street — while the senior Burman discussed royalty matters with C.C. Saha of Hindusthan musical products at Akrur Dutta Lane in central Calcutta. Though English, the insignia of the West, remained Pancham’s Achilles heel, Western music made him espouse long notes and fragmented rhythm patterns. These became part of his DNA.

***

In late 1955, Pancham, along with his parents and Guru Dutt’s unit, came to Calcutta. Burman’s house, registered in his wife’s name — but bearing the plaque Shachin Dev Barman — became his home again for the next few months. Normally the ground floor would be rented out to paying guests, but this time, it had a unique couple as the honoured guests. Guru and Geeta Dutt. The Dutts, along with the Burman family and Sushil Chakrabarty of Melody, the iconic Gariahat music shop, were regulars to fishing expeditions during weekends. On workdays, senior Burman, when not involved with the unit, would frequent the shooting and post-processing of Kartick Chattapadhyay’s Saheb Bibi Golam (1956) at NT 2nd Studio. Pancham would be on a record buying spree. These would serve as his arsenal for Bombay.

***

Ratna Mookerjee, niece of Ashok Kumar and younger daughter of composer Arun Kumar Mookherjee, recollects her initial memories of Pancham. “I saw him during the recordings of Bandini (1963). I was a child and understood precious little, but could sense that nobody used to care for Pancham then. The general consensus used to be: why is he here? The same attitude was accorded to Shammi Kapoor too — a bit earlier perhaps, in the mid and late 1950s. He was seen as an appendage to Raj and Prithviraj Kapoor”.

Pancham had, by that time, completed the score for his first film. It was for the outlandishly bad movie titled Chhote Nawab. Pancham’s music was, however, appreciated by most. Mahmood, his friend who had come up the ranks through sheer grit, roped him again for Chandan ka Palna, which took five years to complete. Hearing Pancham’s compositions for Chandan ka Palna, which was still in the making, his father had remarked that they sounded like Madan Mohan’s or Roshan’s. After Bhoot Bungla’s music was pronounced “rank bad” by some critics, Papa Burman doled out a phenomenal piece of advice — You are being mentioned. That matters. It was then that Pancham went for something that was his real calling. Keep using straight, long notes. Follow the operatic style used in a song like Jago sone walon. Avoid conventional phrases. Use harmonic notes to delineate phrases. Bring forth the brass and rhythm sections. And focus on the mixing. Create a sound which is uncluttered. The incentive for a style he would patent was provided by his father’s dismissive reaction to unsolicited critical feedback. And the belief of another erstwhile “why he”, Shammi Kapoor.

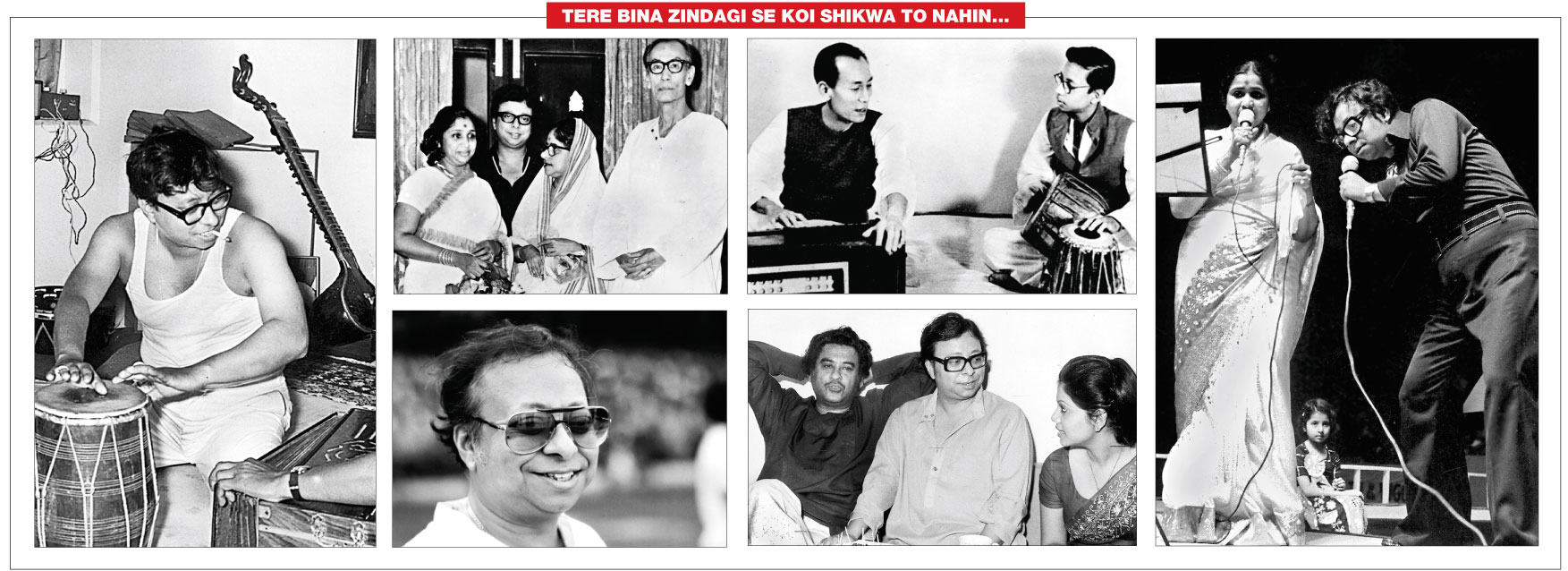

File pictures

And thus we had Teesri Manzil (1966), which got caught up in an unfortunate battle of egos and drove a wedge between Vijay Anand, the director, and Nasir Husain, the producer. Husain had the film withdrawn from the theatres in Bombay a week before it was supposed to celebrate its silver jubilee. But Pancham had started cementing relationships, including a new relationship with the audience. Integrating instrumental portions into the songs was his interpretation of how music in cinema would sound like. While purists thought that Pancham was flouting conventions, in reality, he was adding value to films by giving the director options to cut, swipe, zoom, merge, or dissolve. He visualised the song, something his father too did.

But Pancham’s breaking up songs into uniquely identifiable portions was more the influence of someone like Salil Chowdhury, for whom, a song was 1/3 prelude, 1/3 melody and 1/3 interludes. However, one might notice that Pancham did not carry this rule to Calcutta. It does come as a surprise that for Mone pore Ruby Ray and Phire esho Anuradha, the first Puja songs he sang, he almost followed the format, if not entirely, of a genre he was not very fond of — Rabindrasangeet, which by design, had no place for preludes, interludes or coda. Going back in time, one would also find that Pancham had nearly followed similar arrangement formats for his first two Puja songs — the only basic ones Lata sang for him. And also Ei edike esho, his first Puja number for Asha.

Basic songs did not come with the mandate of visualisation. Ruby Ray was destined to be envisioned through the lyrics, underlining the yearning of a teenager.

***

Today Ruby Ray is a character stretching one’s imagination. More songs have been written about her. One might term it as an obtrusive attempt to jump on to the bandwagon. Little do today’s children know about the expletives reserved for Pancham then, to the extent that one publication decided to put it pretty straight — Singing is a democratic right. Hence Rahul Dev Burman also sings.

Who was Ruby Ray? While some claim that Pancham was infatuated by a lady by that name, the consensus is that the song was dedicated to a certain Chhabi Ray, a lady for whom Sachin Bhowmick would wait outside Lady Brabourne College, Calcutta.

And Anuradha, the lesser celebrated one? Ms Gupta pulled us out of the quandary. “Though I was his mashi, I was only four years senior to him; more a friend and less a guardian. When young, Pancham also used to take refuge under my aanchal — using it like a security blanket, only to be ridiculed by the elders of the house. My marriage was fixed in 1968. It was then that the shy and unassuming lad got his friend Sachin Bhowmick to write a song. For me.”

Another bit of Calcutta probably died within him that day.

This piece is based on conversations conducted by the writers over several years. Many of those interviewed here are no longer with us. Anuradha Gupta passed away in 2014, Subir Sen in 2015, Kersi Lord in 2016 and Sachin Ganguly in 2017.