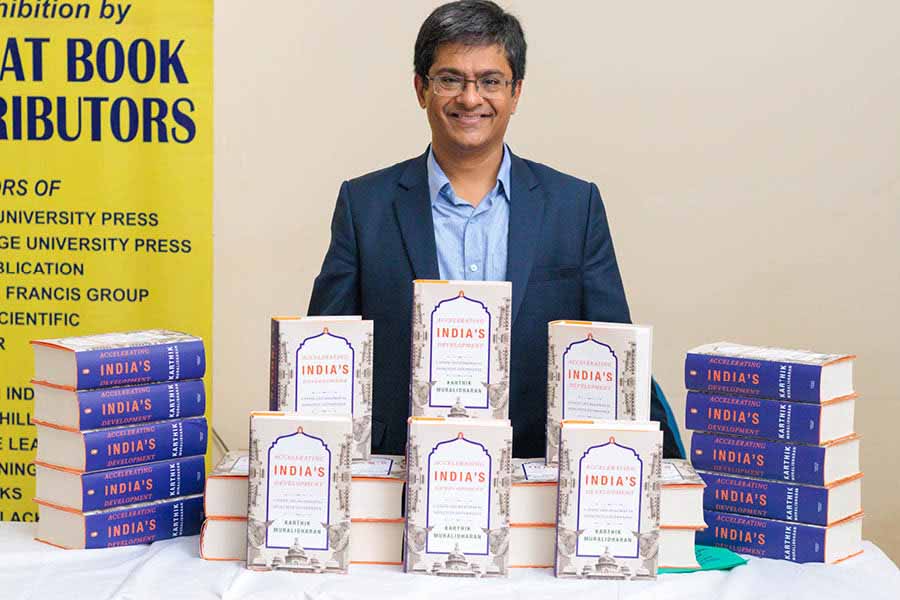

This March, the Tata Chancellor’s professor of economics at the University of California, San Diego — Karthik Muralidharan — unveiled a powerful 800-page book, reflecting upon the drawbacks of the Indian state and possible solutions to overcome them. It is quite rare for an intense academic document with complicated economic concepts to become a bestseller. But Accelerating India’s Development, by Penguin Random House India, has proved that knowledge of economics is not only essential, but can also be made accessible.

In the city for the Arijit Mukherji Memorial Lecture at IIM Calcutta, My Kolkata caught up with Karthik for a chat on the Indian state, his new book, and more. Edited excerpts from the conversation…

My Kolkata: As an academic, how did you make this book palatable and relatable to common people?

Karthik Muralidharan: On the the reasons why the book got so long is because it is the synthesis of a life’s intellectual journey. I was a child of liberalisation. I turned 16 in 1991 and went to Singapore on a scholarship. There, I saw the power of sensible economic policy and how it could transform a country. It began my obsession with government effectiveness.

Most systematic human progress over history has come from the creation of new knowledge, the transmission of knowledge, and then acting on this knowledge. The role of academics is normally to create knowledge. But studying in Singapore and working in the private sector made me appreciate the importance of translating deep academic work into ways that are understood by practitioners.

In 2013, I had written a review paper on education policy and conducted a workshop where Dr Shashi Tharoor was present. He asked me if I was on Twitter. I said, “No, I write serious papers. I don’t do social media.” He replied, “You are directly or indirectly paid by the taxpayer. You owe it to the public to put this information out there.” That prompted me to start posting my new papers, public lectures, recruitment calls and op-eds on social media.

Many people are outstanding economists. Many are good communicators. My comparative advantage is to be at the intersection of research, which has peer reviews from the world's leading technical experts, but with a deep groundedness in India and an understanding of what it takes to communicate that.

Rohini Nilekani said that philanthropists should not distribute solutions, but agency. I went through this journey myself over the past five years. I started the book as an expert who had done a lot of research and wanted to share a bunch of solutions. By the end of this journey, I realised that the book’s real impact would come from empowering thousands of young changemakers with a set of ideas and principles that distribute agency. I'm incredibly privileged for the opportunities I've had, and the purpose of this privilege is to pay it forward.

The book offers an insight into the constraints of the Indian state, along with actionable solutions to unlock India’s full potential

How did the Centre for Effective Governance of Indian States (CEGIS) come about in tandem with the book?

I started thinking about the need for something like CEGIS as early as 2018. My initial idea was to finish the book and then set up the organisation. During an unplanned meeting with Ashish Dhawan, (founder-trustee of Ashoka University) he told me that this was one of the most important ideas he’d ever heard, and the country couldn’t afford to wait. That’s how CEGIS was built as a non-profit parallelly with the book.

We set CEGIS up at the worst possible time in 2019, just before the pandemic. Not much happened for two years, but in mid-2021, a former IAS officer joined as our CEO, and we’ve been doing well organically. I like to not talk about it too much because the real credit goes to changemakers within the government. We are just enabling them to do things faster.

The problem with being a passionate bureaucrat who wants to get things done is that they are so busy firefighting, there is no time to think about things that are truly important. Even if you have the time to think, you don't have the staff to implement it. You then have to do some procurement to get a consultant. By the time you get the consultant, half your term is over. Nine out of 10 times, when big systems are built, they are never used the way they were originally thought of. Hence, you need not only conceptual clarity, but persistence over a time horizon. We provide a little bit of institutional continuity for these deep systemic reforms.

The reason we get to do this is because our relationship with the government is built on trust. As a non-profit, we aren’t here to make money. All of us have taken massive pay cuts to do what we are doing.

Having worked with the government, how hard is it to bring about systemic change?

It’s very easy to blame politicians. A few months ago, I was with the finance minister of a state. He had some 300 people waiting for him. Everyone was looking for help to solve some problem. While bureaucrats are insulated from political pressure, the finance secretary of a major state is still allocating a budget of 300,000 crores a year. There is immense pressure of one corruption scandal anywhere in the system taking you down. Everybody is just struggling to stay afloat. There is very little time to do the deep thinking actually needed to reengineer systems.

The Indian state is like a 1950s Ambassador car. Political parties compete over the direction to drive it, and which passengers to prioritise. But nobody is recognising that the car is barely moving. State capacity and governance needs to be completely nonpartisan because it doesn’t matter which direction you want to drive the car in. You still want a better car. We need to identify a way forward that can be less politically contested.

Since the system has so many dysfunctions, it is very easy to be cynical too. But if you look at the history of how most countries got rich, be it the US or China, their growth was also accompanied by a large amount of corruption. So, corruption by itself does not seem to be an insurmountable obstacle. In our own stumbling way, the level of enterprise and dynamism among Indian people is incredible. We have 1.4 billion people, so even the top 10 per cent comprises around 140 million people. Leadership depends on the best. We have a big population, so we have plenty of the best to drive innovation and build world-leading companies.

You focus more on the state than the centre in the book. Why?

I focus on state-level actions because each state in India is bigger than most countries. Sometimes state leaders and officials abdicate responsibility, believing that the Government of India isn’t doing what it should. But we must ask, ‘What are we doing?’ I urge every opposition to the Central Government to ask themselves what they’re doing in the state that they are governing. The best way to be a credible opposition, is to be a better government in the state you are governing.

I haven’t studied [West] Bengal, but I do ask my Bengali friends, ‘There are so many great Bengali economists, why don't you do more serious work on Bengal?’ There can be various challenges for Bengal’s growth story. It could be the culture, weather and history. Some of it could even be a hangover of communism. I would love for a set of changemakers from Bengal who are committed to this land to take the ideas and principles in my book and contextualise them in a way that applies to Bengal. The book has a broad set of principles, which can be implemented with state-level work.

My simple reading of the recent General Election is that people clearly are not satisfied with what the government has been able to deliver. The problems of unemployment and inflation have not been solved. But the opposition has also not proven that it can solve these. Which is why the verdict is a great validation of Indian democracy. Indian voters are astounding, because they have said that while food grains are good, they would rather have a job. They have communicated to the party in charge that while they seem to be the only solution, they need to buckle up. The question is, are leaders listening to the voters?