After 75 years of Independence, one thing is for sure. We’re far from perfect.

India is a fascinating country, managing to persevere despite its many systemic constraints. However, the current path won’t help us write the growth story of our dreams. This is where Karthik Muralidharan comes in.

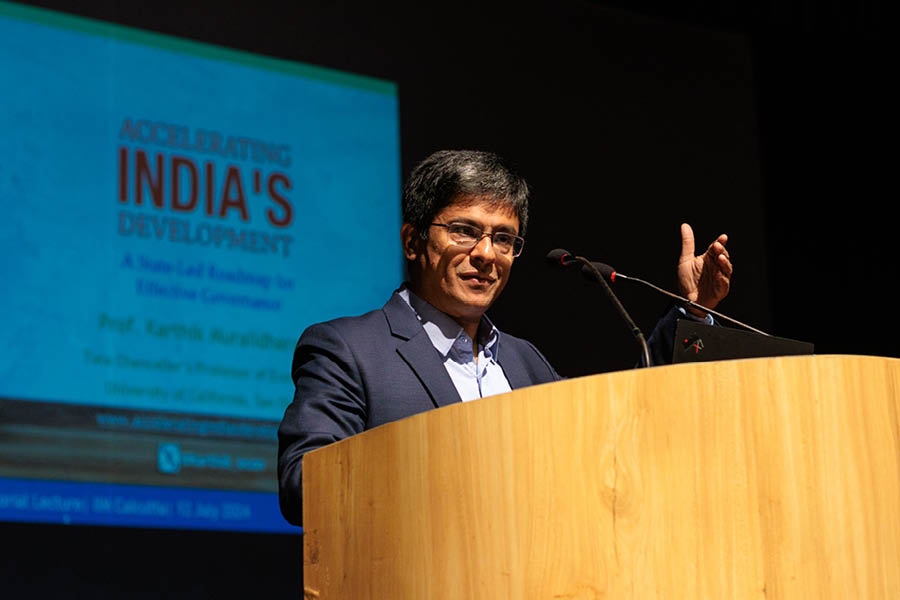

The Tata Chancellor’s Professor of Economics at the University of California San Diego, Karthik’s new book, Accelerating India’s Development, offers a state-led roadmap for effective governance. On July 12, he unveiled the book in West Bengal for the first time, while delivering the Arijit Mukherjee Memorial Lecture at IIM Calcutta, Joka. My Kolkata brings you some excerpts from the talk.

Overview of the India Story

Right off the bat, Karthik addressed India’s billion-plus population, adding that with such large numbers, a researcher could tell whichever story it wished, based on the sample it chose. Enlisting the pros first, he said: “Our size makes us intrinsically important. Our demographic gives us an age structure that will drive growth in the global economy. Our diaspora is a huge asset, which will feed into the India story. We’ve also seen in our recent elections that despite its concerns, India has a robust democracy.”

However, there were multiple cons too. Karthik particularly emphasised upon the challenges in basic service delivery. “Fifty per cent of children in rural India complete primary school without being able to read at a second standard level. We have a 35 per cent stunting rate, accounting for the largest number of stunted children in the world, and 13 out of 15 most polluted cities in the world. Police are woefully understaffed. We have a backlog of 30 million cases in our courts. We have welfare challenges as seen during Covid, and a huge problem of jobs,” he said.

Summing up the India Story, Karthik attributed much of the economic growth to the top 10 per cent. The next 30-40 per cent have jobs that provide services to the top 10 per cent. The bottom 50-60 per cent, primarily in rural India, is left out of the India Story and largely dependent on welfare programmes. “Political election campaigns are mainly about welfare programmes, because that’s how the fruits of economic growth are distributed. But we can’t achieve our full potential, unless we are firing on all cylinders. A key part is by taking the bottom 50 per cent from being passive recipients of Indian welfare, to active contributors of the India Growth Story.”

In order to maximise potential, Karthik expressed the need to focus on government effectiveness in delivering essential public goods and services including environment, education, health and rule of law.

Joking about the book’s thickness owing to its 800-page length, he said: “Someone gave me this interesting compliment, equating the book with a Rottweiler, because it is scary from the outside and friendly from the inside.”

Looking at the bigger picture

Karthik has noticed a common thread over two decades of research, supplemented by his experience in the private sector. “When we demand better healthcare or education, people often equate it with a need for a bigger budget. It’s not just about spending more money. The RoI of investing in governance is often 10 times more than investing in the mere expansion of the programme.”

He backed this with an example of how most of our education budget goes into unconditional salary hikes of teachers. Studies show that this hike has had no impact on outcomes. But when even a modest amount of pay is linked to performance, it has a transformational impact. “Early childhood is the most important time for brain development. Anganwadi, which is the largest early childhood development system in the world, has one worker handling everything from pr-eschool education to nutrition counselling to supplementary feeding. We just provided an extra halftime worker and found dramatic improvements in both learning outcomes and stunting reduction, because it provided the existing worker with more time to focus on health and nutrition. The estimated long term RoI on this is about 1200 to 2000 per cent.” Therefore, Karthik emphasised the need to spend scarce resources better, driven by data. “This book proposes that to accelerate development, we don’t need to necessarily spend more on X or Y. If we can merely tighten the inefficiencies in our existing spending, we can do more of everything.”

He also reflected upon how the scope of a nation state has expanded. Historically, states only focussed on security and law and order. Only in the 19th century, did the state start building massive infrastructure. It is the first time in history that states saw a sustained increase in GDP per capita. Only in the past century have we seen the emergence of the welfare state, which looks after programmes like food security and pensions. This summed up two key points. “Firstly, welfare states are expensive, and most countries took this route after reaching a certain level of prosperity. Secondly, the nature of the state is correlated to its amount of democracy.” While the Indian democracy has a huge moral victory, by providing even the most marginalised sections of society with a right to vote, it also comes with two major challenges.

Karthik was felicitated by IIM Calcutta’s (from left) Abhishek Goel, faculty of behavioural sciences; Saibal Chattopadhyay, director-in-charge, and Bhaskar Chakrabarti, dean of academics.

“Firstly, there is a limited budget with political pressure to spend on welfare. So, there haven’t been funds to invest in capital, or the state itself. For e.g. 50 years after Independence, over 95 per cent of our capital stock in railways was built by the British, because every railway minister wanted to subsidise passenger fare. It made sense from a short term sense but had a cost on the economy and the state.”

Karthik believes that there are several areas where there is a 10x RoI. However, the returns to state capacity come in the long term, while there’s more immediate pressure to spend on programmes that have visibility today. “Secondly, people have the ability to make a claim on the state, but the state does not have the capacity to satisfy these claims. The capacity of people to make claims has been expanded before the state can make them, creating incentives for vote bank politics.”

Can we do better?

Despite the constraints, Karthik remains optimistic due to the data on Indian elections from the past two decades. Karthik has observed a change in the trends, where the old politics of identity and polarisation are only getting politicians 20 per cent of the votes today. For the next 20 per cent, they need to rely on the new politics of governance and service delivery.

He asked the audience to think of the government as an organisation. The factors that drive its culture are data (what are your targets?), personnel policy (what are the individual promotion prospects?), budgets (which divisions are growing and shrinking?), revenue, federalism and decentralisation (what will the local and head office do?), and state versus market (what do you manufacture inside and outsource?).

The talk inspired people far beyond the bounds of IIM Calcutta. (Left) Parikshit Ghosh, a professor at the Delhi School of Economics, and (in right picture) entrepreneur Vatsal Agarwal both picked up copies of the book. “It was a very insightful talk, and addresses the core problems facing the country. I am looking forward to reading about his ideas in more detail in the book,” said Ghosh.

He also pointed towards discrepancy in data, by showing how the official census assessing children’s learning in a state shows that no child is scoring below 60 percent. But upon randomly re-testing the same children on the same questions six weeks later, the learning level was less than half. “Since 2005, Pratham has been doing independent citizen learning measurements, proving that schooling isn’t translating into learning. But government systems can only act according to their official data, where there is no learning crisis. This pattern is found in child nutrition, where everybody is under pressure to make things look good.”

With regards to personnel, Karthik drew attention to how critically understaffed the Indian government was. “The employees per capita in India is smaller than almost any other country. One of the major reasons is that Indian government employees are paid much more than the private sector. We can’t hire enough because we pay too much.” The book comprises many ideas to counter this.

He also pondered on how overcentralised Indian governance is, countering how over 50 per cent of China’s total public expenditure happens at the local level, in contrast to India’s three per cent. Similarly, in China over 60 per cent of public employees are local, while only has 10 per cent.

The session touched upon how the government also sees the private sector as competition when it comes to providing services. “Over 95 per cent of government budgets and staff are allocated towards providing services. As a result, the policies are often skewed to benefit this.” Karthik gave the example of how a tiny country like Singapore has had more tourists than India, because our civil aviation policy was driven to protect Air India. “We limited capacity on every route to prevent foreign airlines from grabbing market share. But the cost to the larger tourism economy was many times of what Air India gained.” The consensus? A government can dramatically increase welfare if they focus on making markets work better, and leveraging private providers to better serve the poor.

The first change Karthik desires to make is for us to switch our language from ‘ruling’ party to ‘governing’, thereby elevating our status from subjects to citizens and pushing us to take a more active interest in governance and demand better from those in power. “High income countries took 100 years to design an effective state. We have it in us to accelerate this in 25 years. We spend so much of our public discourse arguing, but we need to find agendas that we can all get behind.”

You can buy a copy of the book here.