The Centre’s decision to scrap a fellowship that supports researchers from minority communities has dented the dreams of many students from marginalised sections of society.

On December 8, Union minority affairs minister Smriti Irani announced in Parliament the discontinuation of the Maulana Azad National Fellowship for Minority Students (MANF), reasoning that it was overlapping with other grants.

The fellowship, named after India’s first education minister, was launched in 2009 by the Congress-led UPA government.

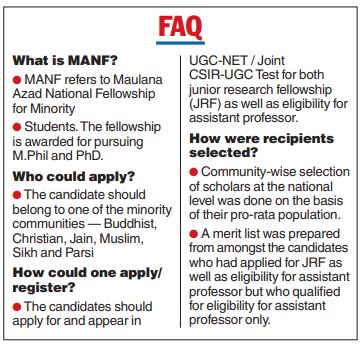

It is open to candidates from one of the minority communities — Muslim, Sikh, Parsi, Buddhist, Christian and Jain — pursuing MPhil and PhD (see chart).

It (the discontinuation of MANF) is a major blow to my research dream,” said Mansarul Hoque, 24, who has just completed his master’s in physics from Jadavpur University and wants to do a PhD in biophysics.

Hoque, who hails from Ausgram in Purba Bardhaman, would have applied for the fellowship very soon “Now, the other option is to apply for the JRF (junior research fellowships), which is far more competitive. If I don’t get selected for JRF, I will have to sit for the test next year. The cost of living in Kolkata and preparing for one more year is not negligible,” said Hoque, whose father is a primary school teacher.

She started going back to school years after marriage but has not looked back since, thanks to grants like the MANF.

“The Maulana Azad grant was extremely useful. Research has its expenses. You have to buy instruments, books and other things. From where I come from, the cost of higher education is a deterrent to higher education,” said Rahman, who has cleared the Bengal state eligibility test (Test) for the position of assistant professor in colleges and universities and is waiting for her interview.

A notice on the website of the Union ministry of minority affairs reads: “The UGC (University Grants Commission) and CSIR (Council of Scientific & Industrial Research) fellowship schemes are open for candidates of all social categories and communities including minorities. Further, students from minority communities are also covered under the National Fellowship Schemes for Scheduled Castes and OBC’s implemented by the ministry of social justice and empowerment. In view of the overlap among the aforesaid schemes — it has been decided to discontinue the MANF Scheme from 2022-23 onward. The existing MANF fellows will continue to receive fellowships till the end of their respective tenure, subject to compliance with the extant guidelines.”

Many existing scholars have refuted the “overlap” reasoning, also made by minister Irani in Parliament. Even if a student is eligible for multiple grants, she can avail of only one, they said.

Md Aminur Rahman Ansari, 27, who is pursuing a PhD in agriculture sciences from the Uttar Banga Krishi Vishwavidyalya in Cooch Behar, is a recipient of the MANF fellowship.

“I was eligible for the National Fellowship for Other Backward Classes as well. But I had to choose between MANF and the OBC fellowship,” said Ansari.

He gets a grant of around Rs 40,000 a month, including HRA and contingency allowances.

From Delhi to Bangalore, the government’s decision to scrap the fellowship has fuelled protests from student groups across the country.

The decision is in line with the BJP regime’s anti-minority drive, the protesters have alleged.

The Maulana Azad fellowship was introduced on the basis of the recommendations of the Sachar committee, set up by the UPA government and led by retired Delhi High Court Chief Justice Rajinder Sachar to study the socio-economic condition of Muslims in India.

In 2006, the panel submitted its report. It showed that Muslims were socially, educationally and economically lagging behind other communities in India.

The Maulana Azad fellowship is open to all religious minorities, but Muslims happen to be the majority of its recipients. Out of 1,000 MANF fellows in 2018-19, as many as 733 were Muslim, according to government data,

“This fellowship has proven usefulness. The participation of minorities in higher education will go down because of the decision to stop it. The BJP was originally opposed to the Sachar committee and subsidies to Muslims. But there is a larger political and symbolic message behind this decision. Maulana Azad was a Congress leader. He was ideologically opposed to Pakistan, as was a significant section of educated and liberal Muslims. The BJP’s idea is to decimate the idea of secular nationalism,” said Maidul Islam, a Calcutta-based political scientist.

“The BJP wants to push Muslims further back. So that they are more ghettoised, more cornered and more trapped in communal politics. That is their larger plan,” he added.