By the time the flames sink into the night, they would have come and gone. Drifted in, lingered awhile, and then drifted out again. Invisible, formless, but content, that they hadn’t been forgotten.

They?

The dead.

Outside in the blue-black night, the sky lanterns stare back at the stars. Not too long back, you could even sense the nip in the air.

The nip’s gone, but the lamps will be back again this coming Sunday on the eventide of Bhoot Chaturdashi, the night before the goddess emerges, raised kharga over terrifying garland. The night when 14 little oil lamps will flicker on a thousand doorsteps and on windowsills, lit gently, palms cupped against the autumn-end breeze.

Symbolic reminiscence

The lighting of lamps on Bhoot Chaturdashi is a tradition that has long been followed in this part of the country; nobody remembers how long, but that’s how it has been, embraced in all the contradictions that the word bhoot serves up. If the adjective ‘bhoot’ means the past, a time that once existed but does not any more, the noun ‘bhoot’, as part of the Hindu concept of ‘Panchabhoot’, implies the five elements of nature, as real and present as the past is not. Then there is the pronoun ‘bhoot’ that means ghost, which hints at a supernatural existence that may have had a past.

On the day before Kali Puja, the word bhoot lends its multiple interpretations to the word chaturdashi, or the 14th day of the lunar fortnight in the Hindu calendar, a haunting, numinous conjunction that elevates what would otherwise have been an ordinary evening to something symbolic. The tradition of lighting 14 lamps, or diyas, or eating choddo shaak, 14 types of greens, is an extension of that symbolism.

According to one long-held belief among Bengalis, the light from the lamps guides their departed ancestors to their homes when they return to earth for a day on Bhoot Chaturdashi. Some also believe that these diyas are dedicated to Yama, and that the god of death and dharma can even figure out who have not forgotten their ancestors. Then there are those who believe that the 14 diyas keep away unholy spirits who visit the world of the living on this day. So keep the lamps lit, whatever the case may be. As for the dead who have passed on, they can never come back, but they return as memory, nourished in this symbolic reminiscence by those they have left behind.

The evening ritual of lighting lamps is not limited to this side of Bengal only. In many places across the border in Bangladesh, once part of the same land, people use leaves of the jackfruit tree in place of diyas. Tradition survives in different ways.

Sometimes it flows too — in changing perceptions.

Hear it then from a young man. Parthib Banerjee, a student in his early twenties, recalls how the meaning of Bhoot Chaturdashi evolved for him as he grew up. “First, there was a sudden fear about seeing a ghost, then it became a curiosity,” he told My Kolkata. “Now, this special day reminds me that nothing is for ever.”

‘Halloween is a more familiar term than Bhoot Chaturdashi,' said art student Aheli Chakraborty, adding, ‘just like cakes and pastries are more popular than pithe-puli’

A more matter-of-fact assessment of the place of tradition in today’s world, perhaps, came from art student Aheli Chakraborty. “Halloween is a more familiar term than Bhoot Chaturdashi,” she said, “just like cakes and pastries are more popular than pithe-puli [the winter-special sweet treats].”

The world has moved on. It’s no longer what it used to be when the real and the metaphorical lived happily together. But there are some, though increasingly dwindling in numbers, who still have no problem with either. “Bhoot Chaturdashi is a day when the journey begins towards light after the conquest of darkness,” said Ranjit Bhattacharya, a retired bank officer, for whom the day’s rituals have been part of his life for over 65 years. “Darkness is a relative word, as light is present just behind it.”

‘Bhoot Chaturdashi is a day when the journey begins towards light after the conquest of darkness,’ said Ranjit Bhattacharya, a retired bank officer Shutterstock

A hint about this movement from darkness to light also comes from Sourav Chakraborty, man of god, who invokes Yama. “If anyone has committed a mistake unknowingly, they can correct themselves on this day through a special lamp dedicated to Yamaraj. It’s a way of acknowledging one’s fault to uplift one’s self,” said the priest from Kolkata, who is associated with the Kamrup Matth, Varanasi. “The time of Bhoot Chaturdashi is a time of transition to rectify one’s own self.”

For the season too it’s a time of transition, from autumn-end to the beginning of winter; the festival of Kali Puja the divine junction between the two seasons.

Same day, different tradition

While Bengalis celebrate Bhoot Chaturdashi, elsewhere in the country, in the north and the west, people observe the day as Naraka Chaturdashi, a prayer ritual said to have been started by Lord Vishnu himself. The story goes that King Bali, a powerful ruler, had taken the form of the asura (demon) king Narakasura as he set about conquering all the three worlds. Even the gods were not spared in the king’s relentless march to expand his realm.

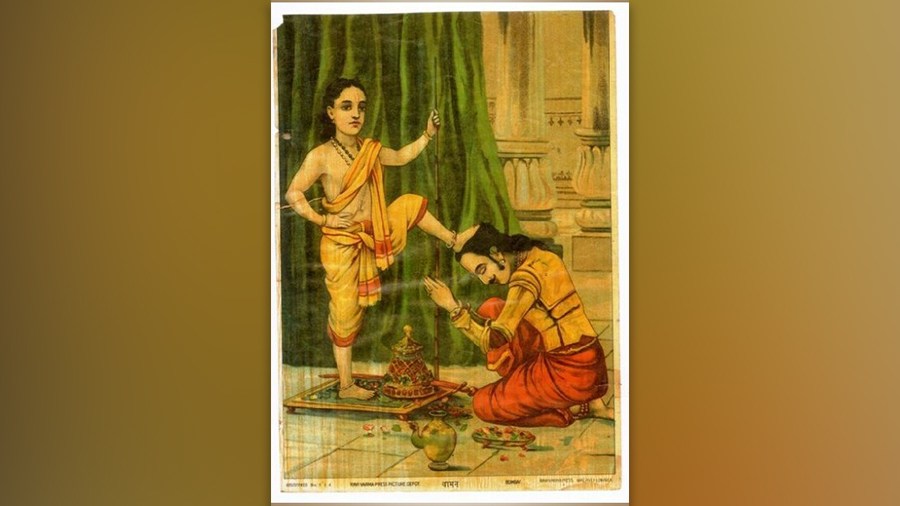

The gods then approached Vishnu to save them. Vishnu refused to join the war, or kill his own devotee, but presented himself before the king in his Vamana avatar of a dwarf Brahmin with a request for three steps of land. When the king granted his wish, the Vamana transformed himself into Vishnu’s colossal form, winning back both heaven and earth. The king, realising his fate, offered his own head for the third step and was pushed down to hell.

Vamana, an avatar of Vishnu pushes Mahabali down to patala (hell) with his feet (painting by Raja Ravi Varma) Wikimedia Commons

But Vishnu had realised that Bali had agreed to donate the three steps of land fully aware of the dwarf’s real identity. Grateful, he started the tradition of offering prayers to the king in his Narakasura form. Since then, so goes the legend, King Bali would visit the earth on this day accompanied by his subordinates, ghosts and spirits, and ask for prayers and offerings.

The day is also celebrated as Chhoti Diwali, the second day of the five-day-long festival of Deepavali/Diwali. According to ancient Hindu literature, Narakasura was killed on this day by Lord Krishna and the goddess Satyabhama.

In Bengal, though, the local belief is that the goddess Kali herself descends on earth with 14 spirit attendants before she embarks on a mission to defeat the unholy spirits.

'Choddo shaak'

The symbolism of the number 14 also plays out in the form of another ritual on Bhoot Chaturdashi — the custom of eating 14 kinds of herbs, or choddo shaak: Ol, Kalkasunde, Jayanti, Neem, Kenu, Beto, Shanche, Mustard, Hilanch, Palta, Gulanch, Bhatpata, Sheluka and Shushani. That corresponds to the second interpretation of bhoot, the five elements — kshiti (earth), awp (water), tej (fire), marut (air) and byom (sky) — into which the human body dissolves after death. Before these herbs are fried, they are washed with water, which is then sprinkled around the house in the belief that when the ancestors return they can find nourishment at every corner of the dwelling they once lived in.

As with most customs, this too has a practical reason behind its development. Not surprisingly, the plants and vegetables named in the list of 14 have been used for medicinal purposes in traditional medicine as a way of strengthening the body’s immune system. “The 14 plants actually work as medicine in this time of season change,” Dr Debasish Pahari, PhD, who has been practising ayurveda for over 25 years, told My Kolkata. “This is the time when viral fever and different types of flu are common. The herbs are also good for digestion. They clean up the colon and detoxify the body.”

But just as traditional systems of medicine like ayurveda have been overtaken by modern medicine, traditional customs like Bhoot Chaturdashi have long ceded ground to modernity. Yet the day will return every year, inscribed on the pages of the Panjika, the Bengali almanac, for people like Bhattacharya, the retired bank officer who says the day is a reminder that he owes his existence to his ancestors. And he is “grateful to them” for bringing him here.

Implied in the words is a feeling of reassurance: the reassurance of being alive. And, perhaps, also the hope that one day, lamps will be lit for those who are lighting them now when they disappear into the void. That’s how tradition flows down the ages, just as this evening of the lamps has done.