Although we’d like to believe that history is stationary, it is constantly being rewritten. For a historian, there is discomfort in claiming that something is the ‘first’, the ‘worst’ or the ‘best’. The historical record necessitates re-evaluation, disallowing superlative claims. When slogans like “Babar ki aulaad” or “Aurangzeb ki santaan” litter the public sphere, what role does history and its byproduct — historical fiction —play in India, especially when it is deliberately, often misguidedly, reconstructed?

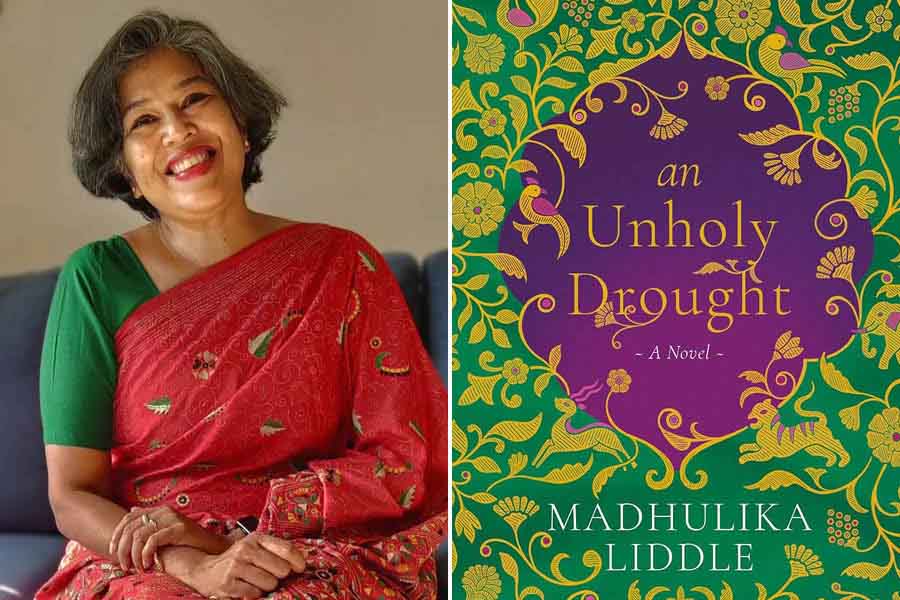

While a historical novel is fiction, well-researched ones expose readers to major events, figures and cultural contexts of particular historical eras. By infusing a narrative into factual history, this genre gives readers an engaging entry point to learn about the past. The past suddenly becomes personal and a part of the present, as is the case with Madhulika Liddle’s An Unholy Drought (Speaking Tiger Books), which ends shortly after Akbar’s decisive victory at the Second Battle of Panipat in 1526, marking the continuation of Mughal rule in India.

A multi-generational saga set in Delhi during the 15th and 16th centuries, the novel begins with Daanish, a young letter writer. Daanish, embroiled in a scheme orchestrated by his friend, Mushtaq, is arrested and imprisoned, eventually forced to sell a family heirloom, a priceless stone frieze called “The Garden of Heaven”, to pay his debt. He leaves Delhi to atone and finds a new life in Sirhind as Buland Baba.

Years later, Daanish’s nephew, Qasim, locates Buland Baba after he learns about his uncle’s true identity. When he dies, Qasim, driven by a sense of duty, attempts to track down the buyer of the frieze to reclaim this heirloom, sceptically aided by his wife, Aabida, a strong and resourceful character unafraid to challenge societal norms. She becomes a successful brocade weaver, while Qasim eventually abandons his quest at her request.

The story unfolds through generations, following Qasim’s son, Zubair, who falls in love with a Hindu man, only to be betrayed by him, and finally Zubair’s son, Nadeem, who grapples with the legacy of his ancestors and their workshop. As the novel ends, the young Akbar, Humayun’s son, is poised to take the throne. It’s not exactly a cliffhanger, but you’re left with a desire to know more, even if there isn’t a rush of anger at being denied that knowledge.

An Unholy Drought is the second volume of the “Delhi Quartet”, and although I didn’t read the first book, The Garden of Heaven (2021), I didn’t feel I missed much. The fact that the second instalment can stand alone is a testament to Liddle’s worldbuilding skill. She transports the reader to Delhi from the 15th century, seamlessly weaving historical details about clothing, architecture and customs into the narrative. These details aren’t merely decorative. In fact, you don’t notice the details for the most part, just as you don’t notice a well-crafted movie set. The action keeps you occupied.

Glossing over sentiments

Liddle’s writing unknots the parts of history that are seldom spoken of. This is perhaps why I was surprised to note that the novel relegated the concept of “Ram Rajya” to a single page. Even if it doesn’t endorse the idea, the scant attention it receives sits uneasily, especially in today’s polarising times.

There are a few Hindu characters, and even fewer that leave an impression. This includes the Hussaini Brahmins, a community resisting the injustice they face under the Lodhis. Towards the end of the novel, a Panditji expresses a longing for a return to Hindu rule, believing that a Hindu ruler like Hemu would remodel the country into a Ram Rajya. (Given Hemu’s Muslim allies, Nadeem and his grandson scoff at Panditji’s optimism regarding the king’s motivation.) After this instance, the idea of a Ram Rajya is not revisited, at least not in this volume.

The novel has more than 10 fully fledged characters and a barrage of possible perspectives, but the one the reader encounters the most is sanitised. For the first few hundred pages, I thought the narrator was a woman. It was, in fact, Nadeem, who narrates the story of his family to Mohsin, his grandson. While the rest of the narrative employs a third-person perspective, these conversations between Nadeem and his transcriber form the ‘Interludes’.

Nadeem’s voice isn’t overtly feminine, but the subtle, tender sensibility in his narration sticks out. Perhaps the muscle memory developed from writing The Garden of Heaven, narrated by a female character, had latched on to Liddle. It’s not that a man can’t empathise with a woman, but Nadeem seems to go out of his way to insist that he can.

‘The money-lender refused to let her bring Gokul into the house,’ my son tells me, while Mohsin takes Gokul inside. ‘The younger children he accepted; Gokul, no.’ He tells me that the money-lender, however, has agreed to send some millet for Gokul every month. When they went to Gokul’s home yesterday, they found the boy alone and distressed, and he told them all that had happened. They took him off to forage in an attempt to distract him, and got back late this evening. They have brought Gokul with them, as also a small sack of millet that his new stepfather had sent for him.

‘The poor child,’ he says. ‘He must feel so rejected, abandoned in this callous fashion. What a heartless mother.’

I cannot help but wonder. Was she heartless, though? Or did she simply see that her younger children could be saved from starvation if she gave herself to the money-lender? And was she responsible for the money-lender’s agreeing to send millet for Gokul? I doubt if he would have offered to support this boy out of sheer magnanimity.

In a novel where gender roles are clearly defined, Nadeem’s sensitivity, while comfortable, is unconvincing. It feels like a salve for the male characters’ flawed interpretation of fellow female characters.

Unfortunately, without context, it’s often challenging to convince readers that stock characters — in this case, Gokul’s mom — are more complex than they seem. But in giving this perspective the way she has, Liddle stirs the reader’s understanding of Nadeem, immobilising our ability to brand him as good or bad. This might seem like a virtue, but also comes with the disadvantage of making Nadeem, the character, and Nadeem, the interpreter, seem like two different people. The narrator is a man unusually at ease with his masculinity, but the novel doesn’t seem to inspect why that’s the case.

Moving beyond the male gaze

The strength and resilience of the novel’s female characters cast a spell on its story, lifting it up. Aabida, a master of strategy, defies the role of a dutiful wife by acting on her own initiative to ensure the well-being of her family, becoming a successful craftswoman who sets up a stable source of income for generations to come. Although she was thwarted by her father for speaking her mind to her husband, she insists that’s the least she can expect of a marriage, a union that doesn’t even pretend to equally serve all involved.

This comfort is colder still when the reader encounters Shahana. First portrayed as a timid and shy figure easily intimidated by the more assertive characters around her, she is loyal to Zubair even when he chooses to pursue another man. She actively orchestrates a conspiracy to help him escape from prison, putting herself at risk, refusing to accept that she is helpless, a testament to the fact that Liddle’s female characters don’t see their womanhood as a limitation.

Across the novel, there are few physical descriptions of these characters, with Liddle deliberately refusing to serenade their beauty. While some key female characters, like Aabida and Zarina, are acknowledged as beautiful, those accounts are often fleeting and not elaborated upon. By leaving physical description out of the characterisation, Liddle asks us to pay attention to who these women are, as opposed to enabling a gaze that fixates on their physical appearance.

Cleopatra was a highly educated and intelligent ruler, but conversations about her beauty overshadow her character. The default male gaze can be unforgiving, after all. Liddle is a writer who wants to change how we talk about women. I’d pick up the novel simply to run into her female characters.

Diya Isha is an editor at a Delhi-based publishing consultancy. You can find her on Instagram as @contendish