“Everyone has a book inside them. We can help you to create yours!” Or so goes the advertising pitch of a certain online writing academy. Well, maybe. It might not be a very good book, of course. Handing over your money will be the easiest part.

What is certain is that if you are a mere mortal (and not literary a genius), then the road to writing and getting published will be an arduous one. It will not harm you to have some support along the way, especially from those who have travelled that road themselves.

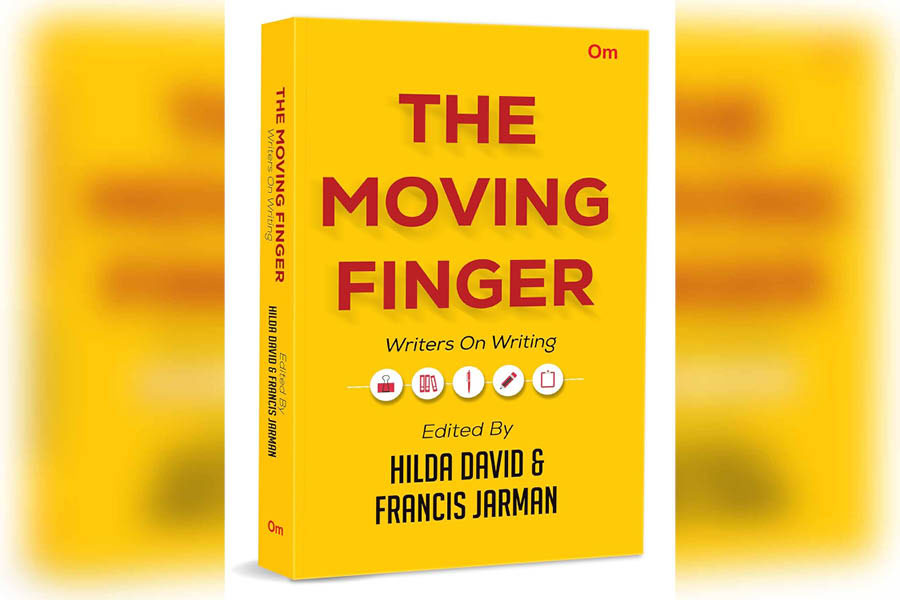

This was the starting-point of The Moving Finger: Writers on Writing (Om Books International), published this February. We had the idea to gather material on writing from successful practitioners in different genres. Not theoretical literary criticism, but also not banal tips and tricks (like “keep your sentences short”, “avoid adverbs” and so on).

The ‘we’ being Hilda David and myself. Hilda and I had met through a successful partnership between our two universities — Symbiosis in Pune and Hildesheim in Germany — involving staff and student exchanges and joint research projects. We were both university teachers and novelists and were also involved in theatre (as director or dramatist). We had both taught creative writing. We had also collaborated on editing a couple of books: India Diversity (Om Books International, 2017) and Text Wars (Oxford, 2021).

The Moving Finger is our third project, and we were well set up for it by having had so many distinguished writers included in the earlier books. When we contacted them, some indeed said “yes, count me in”. Others said “no”, but recommended other writers whom they knew. In addition, there were some useful facilitators, people who know the Indian literary scene well, such as our editor at Om, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, our agent, Suhail Mathur of The Book Bakers, and Premila Paul at SCILET, the Study Centre for Indian Literature in English and Translation in Madurai.

Many writers find it awkward to reflect on what they themselves are doing

Persuading writers to write about writing is harder than it sounds, for two main reasons.

Firstly, they are busy people, who may also be trying to earn a decent living from their work. To their credit, none of our contributors asked for money. Nor did we offer any. Understandably, though, a few of the writers we approached declined because they were simply too busy.

Secondly, many writers find it awkward to reflect on what they themselves are doing. As opposed to writing about other authors or reflecting on writing in general. It is a bit like stopping to consider how you breathe (or ride a bicycle), and then…oops, finding yourself in difficulties.

Yet many said ‘yes’, and so we were able to assemble a team that included experienced professionals, promising newcomers, best-selling authors, Sahitya Akademi award winners and recipients of prestigious national and international prizes. It has been a privilege working with them, and we are grateful for the very many personal insights that they have shared with us.

What will you find in this book? With a couple of exceptions, all the contributions are by working practitioners in different genres. These genres naturally include the “big three” — novel, drama and poetry — but also the short story (Anjum Hasan), writing for children (Paro Anand), writing for television (Gajra Kottary), and humour (Krishna Shastri Devulapalli).

We also have such topics as the role of memory in writing (Gita Viswanath). There are essays on how to write about love (Simran Paul) and about psychopaths (Heena Rathore-Pardeshi) — treated separately, I might add — though T.W. Geraghty’s essay on writing about sex could easily have been titled “How Not to Write about Sex” because of the hilarious examples of bad writing that it quotes!

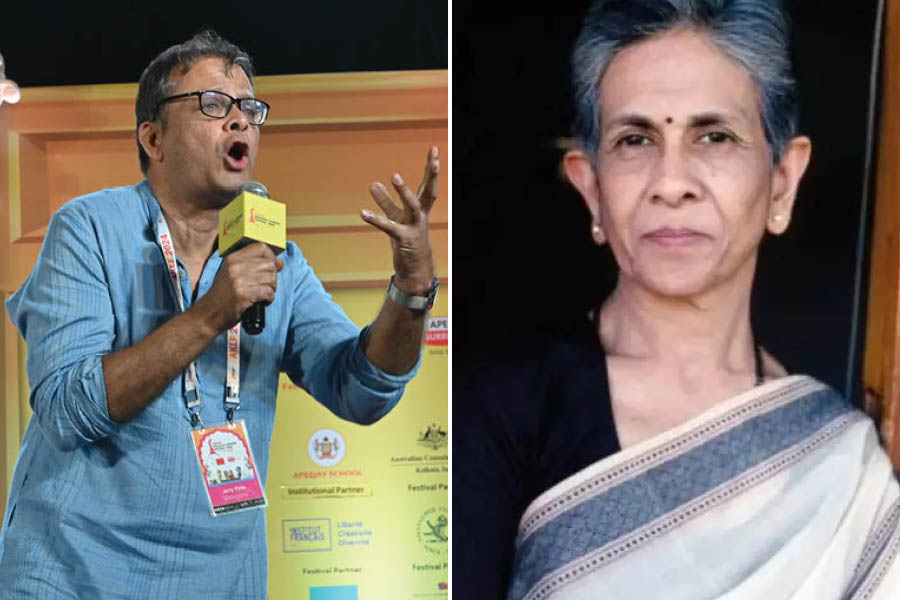

Contributions from Jerry Pinto, Shanta Gokhale, Shashi Deshpande, and more

In the book, Jerry Pinto (left) writes on translation while Shashi Deshpande writes about the process of writing TT Archives

There are articles about specific forms of fiction, such as mystery (Manjiri Prabhu), fantasy (by myself), mythology (Suhail Mathur), and historical fiction (Christoph Werner), and differing but personal takes on the writing of poetry by two distinguished poets, Arundhathi Subramaniam and Randhir Khare. Jerry Pinto provides a delightful allegory of translation. Shanta Gokhale reveals that there are “Many Ways to Make a Play”, while Ramu Ramanathan intriguingly advises young playwrights to “follow their nose”. And there is a lively essay by the master of Indian noir, Zac O’Yeah.

Young Indians with good language skills and an interest in science and technology can actually earn a good living from their writing through technical translation. (Bear in mind that very few poets, novelists and dramatists ever make serious money from their work.) Bruce W. Irwin’s explanation takes the form of a recipe, an approach also taken (logically enough) by Ramona Sen in her article on food writing.

The collection is book-ended by perceptive essays by Shashi Deshpande (“About Writing”) and Anil Menon (“A Writing Life”).

You would have noticed a few non-Indian names. Most of our authors live in India, but we also have contributions from the Indian diaspora, and from the US, the UK, Ireland, and Germany. That is by way of a reminder that, as Hilda points out in her preface, wherever you are, if you write in English, you are part of what is arguably the world’s greatest literary tradition. And Indian writing can now stand comparison with the very best writing in English.

The road to writing is not an easy one, although we believe that our book will be of help to those who are considering embarking on it, or have already done so. What is the reward (apart from the fame and riches that might, though more probably won’t, be achieved)? Let Shashi Deshpande have the last word. The hard work and the frustrations are more than made up for by those moments, she says, when the words flow and her pen glides across the paper, moments that are “like tasting a slice of heaven”.

Get your copy of The Moving Finger: Writers on Writing here.