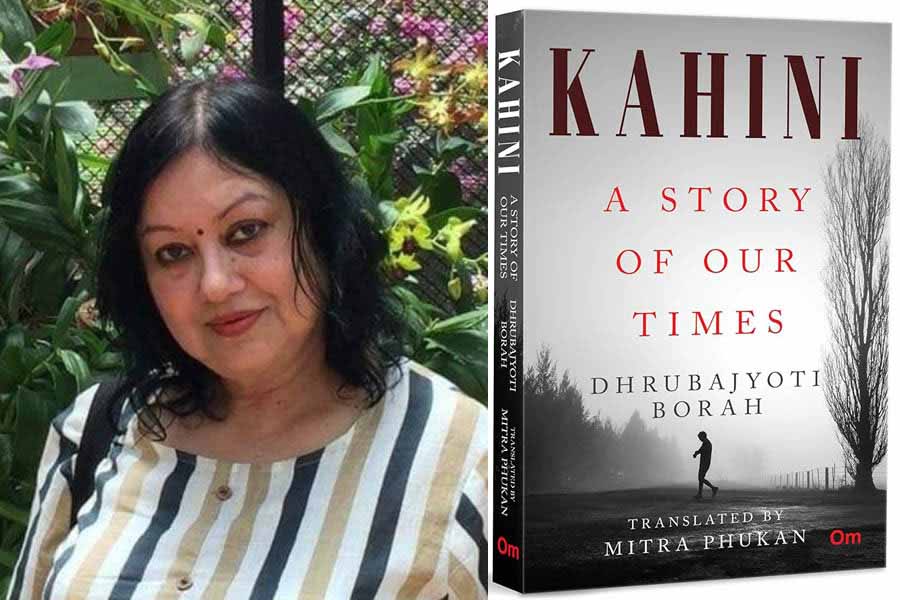

Like many hitherto inaccessible literary cultures in India, writings from the country’s Northeast, particularly Assam, are now embracing a much wider readership as they enter the lingua franca of English. Prolific and sensitive translator Mitra Phukan discusses this development with My Kolkata following the recent release of Kahini: A Story of Our Times, a layered family and social drama, published by Om Books International. Phukan’s version is the English account of Assamese writer Dhrubajyoti Borah’s 2008 novel of the same name.

Phukan is a writer, translator, columnist and trained classical vocalist. Her published works include four children’s books, a biography, the novels, The Collector’s Wife and A Monsoon of Music, and a collection of her newspaper columns titled Guwahati Gaze. Her latest works include a translation of the Assamese novel, Blossoms in the Graveyard, and A Full Night’s Thievery, her own collection of short stories. Edited excerpts from the conversation with Phukan follow.

‘Kahini is full of irony, which can translate badly if one isn’t careful’

My Kolkata: Losses in translation are inevitable. What kind of challenges did you contend with in keeping the culture and context alive in your English rendering of Kahini?

Mitra Phukan: Kahini is rooted in the contemporary realities of Assam. The extortion, sometimes by fake organisations, the corruption of different kinds, the avarice and rampant materialism — all find a place in the book. However, there’s no preachy tone at all. Getting the right tone across while translating the realities portrayed was challenging. Also, it’s full of irony, which can translate badly if one isn’t careful. There’s much humour, satire and sarcasm, too. Sometimes the tone is savage, but it’s never bitter. And yet there’s tenderness in the descriptions of the mother’s first home after marriage in the foothills of the mountains. Translating these tonal variations is always a challenge.

To get all the nuances was difficult, not least because of the conversational style in which the story is couched. Besides, I had to clear my mind and forget about my personal style of writing novels, being as close to the style of the author as possible. That’s never easy.

Also, because of this conversational style, the work in Assamese is sprinkled with many English phrases and quotes. This is what happens when we speak — we use several languages in a single sentence. But when translating into one of those languages — English in this case — it becomes difficult to constantly point out these switches from Assamese to English. Because these switches are important in the text, it wouldn’t be enough to simply gloss over the fact that they are in another language. The use of Hindi and English is also specific to the character delineation. Plus, there’s Raghu, who speaks in a delightful rustic Assamese. I feel I’ve failed to put across the authentic accent of Raghu Kai. I have still not found a way to bring across the lovely accents of rural characters either in my own works in English or in translations.

When it comes to the context, there are the usual challenges of putting across the particular cultural context without interrupting the flow of the story. I have tried to bring these in as unobtrusively as possible. In Kahini, there’s a clear hierarchy in the extended family, which is normal even in urban areas. I wanted to put across a sense of this without actually articulating it in the translation as such.

‘Literature and art are supposed to elevate the human mind and consciousness, but here they are mingled with killings’

“We come from a really fortunate land/ Our executioners and assassins wield both gun and pen.” So goes a lovely couplet in the book. In the world of Kahini, what role does poetry occupy in socio-political critique, given that it serves not only as the vehicle (the text is replete with poems by Shakespeare, Yeats, Sumitranandan Pant, etc., which are voiced by a major character) but also as the backdrop (scenes of mushairas)?

The reference in this couplet is to the insurgents who actually did wield both gun and pen. Many of them were very well-read, but they were also ruthless in their violence. The savage satire and irony of these lines startle the reader, but they are completely based on truth. Literature and art are supposed to elevate the human mind and consciousness, but here they are mingled with killings.

Conversely, we have many on the ‘opposite’ side. For example, police personnel and other law enforcers, people who have been entrusted with bringing these insurgents to justice, who are also renowned poets, novelists and short story writers. There’s a mention of this in the book, too.

The purpose of art and culture in the book is to show how one can be an extortionist and yet be a “cultured person”. There’s subversion there. It also shows the hollowness of the cultural scene and the importance of money. The grandfather becomes a fake extortionist, not so much for money but to teach his corrupt family a lesson in a society that seems to have lost its moral bearings. He quotes poetry and appreciates culture.

There are quotes from King Lear about age, which are certainly very relevant in this context. The purpose of the discourses on the Vedas is possibly to elevate. One can be an extortionist, a fake terrorist, and yet understand these lofty concepts. The two categories are not mutually exclusive.

With increasing translations, especially in English, India’s Northeastern literary scene is becoming more vibrant, forging connections with readers not only in the ‘mainland’ but in the world at large. Are there some unexpected implications, cheering or challenging, of this movement from the local to the national to the global?

I find that some excellent works, both fiction and non-fiction, remain untranslated. This is especially true of earlier works of fiction, drama and poetry. This distresses me because the work remains inaccessible to those who are outside Assam and those who don’t know or read the language. In the realm of humour, especially, I find that many earlier works have remained untranslated.

Also, I wish there would be more translations from Assamese into other Indian languages, not just English. Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, among others, and also neighbouring languages such as Bodo, Bengali, Khasi and so on. I’m talking about direct translations and not translations via English.

Soumya Duggal is an editor and freelance writer on culture. Currently working in publishing at Om Books International, her previous stints have been in business and climate journalism. She studied English and comparative literature at university, and her master’s thesis explored the Seraiki diwan of the 19th-century Sufi poet Khwaja Ghulam Farid.