Multiple iterations of the Ramayana have featured at the forefront of the public imagination in India. More often than not, the political and religious ramifications of the epic have eclipsed its cultural, literary and historical value. The Sea of Separation (Harvard University Press), Philip Lutgendorf’s most recent English translation of significant episodes Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas, is a timely reminder of the poetic value the Ramayana possesses in the canon of global literature as well as for an Anglophone readership.

Myths pervade and sustain our everyday life in ways we rarely recognise. Over centuries, they shape the collective imagination of a race or a community. This is pertinent in the case of the Ramayana — a saga of the Hindu god Vishnu’s descent into the human realm as his seventh incarnation, Ram, king of Ayodhya, to eradicate the evil demon, Ravana. An allegorical take on the battle between good and evil, the Ramayana, like most epics, also becomes a humanised tale of love and devotion between Ram and his wife, Sita. It is no exaggeration to suggest that the Ramayana is a cultural monument that represents a series of values that is revered in the Indian ethos.

Lutgendorf’s edition preserves much of Tulsidas’s original style, retaining its rhythmic grandeur

Philip Lutgendorf is a prominent scholar of Hindi and modern Indian studies Wikimedia Commons

Many versions, retellings and editions of the Ramayana abound, of which Valmiki’s Ramayana is considered the first Sanskrit precedent. Indian poet AK Ramanujan argued that the number of Ramayanas and the range of their influence in South and South-East Asia over the past two-and-a-half millennia are astonishing. Yet, the most popular and widely circulated retelling of the story is the one composed by the famous bhakti poet Tulsidas, a contemporary of the Mughal emperor Akbar, who rendered the epic in Awadhi and published it as Ramcharitmanas.

Philip Lutgendorf, a prominent scholar of Hindi and modern Indian Studies, offers a dynamic and lucid free-verse translation of some of the most famous episodes from Tulsidas’s Manas. For centuries after its inception, Manas has remained the most popular version of the epic in North India and a pioneer of classical vernacular literature. It has been adapted into countless local dialects, performed in theatre and even presented on television. Tulsidas’s retelling enriches the oral, literary and dramatic tradition of the Ramakathas or stories of Ram. The poem’s literary force derives from the ideology of bhakti or devotion to Vishnu. The sustained hymn-like tone of bhakti writing replicates the devout frenzy of the devotees who worship Ram as transcendent divinity.

Lutgendorf’s edition preserves much of Tulsidas’s original style, retaining its rhythmic grandeur while making it accessible to an English-speaking audience. In discussing the unique repetitiveness that recurs in several phrases and epithets of the poem, the translator points out the linguistic differences between Hindi and English. But while it is impossible to completely duplicate the dizzying, almost hypnotic rhythm of Tulsidas’s verse, Lutgendorf succeeds in translating its clarity, compactness of expression, and a certain momentum.

Morally ambivalent moments of the epic are brought to life again and again by the translation

Manas comprises four interwoven dialogues — between the Hindu deity Shiva and his wife, Parvati; between the Vedic sages, Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaj; between the immortal crow Bhushundi and the divine eagle Garuda; and finally Tulsidas’s argument presented to his audience. The Sea of Separation handpicks well-known episodes of the poem in three sub-books called “In the Forest”, “The Kingdom of Kishikindha” and “The Beautiful Quest”. The tale includes the years of Ram’s exile and his disputes with the race of demonic beings called rakshasas, leading to the abduction of Sita. This is followed by Ram’s alliance with the divine monkeys and his worshipper, Hanuman’s, feat of visiting Lanka to send news to Sita. Each sub-book commences with a grand invocation to the gods and jumps into the thick of things, being voiced by narrators who, as Tulsidas’s mouthpieces, celebrate Ram’s deific valour.

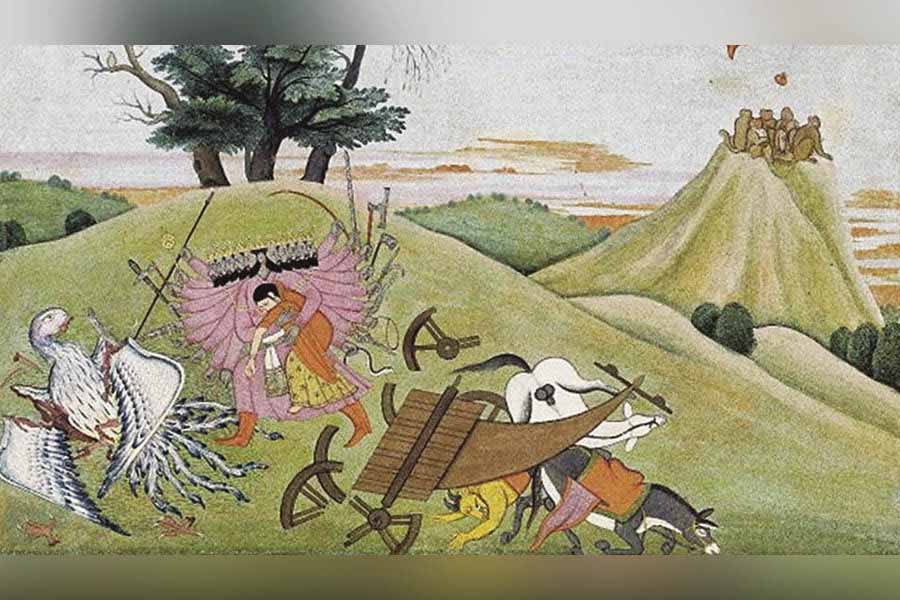

The 46 stanzas of “In the Forest”' alternate between Ram’s encounters with sages in the forest and violent demons. The poetry is as robust as it is adulatory when narrating the hapless fate of Surpanakha, Ravana’s sister, who tries to seduce both Ram and his brother, threatens Sita’s life, and has her nose and ears sliced off by Lakshman. Retribution is swift and brutal as Ravana plots to avenge his sister by luring Sita with a demon disguised as a golden stag and kidnaps her. The vulture Jatayu’s noble attempt to rescue Sita is narrated with grandiose descriptions and his death in the arms of Ram is poignant.

The next section deviates from the main storyline of Sita’s rescue as Ram comes to the aid of Sugriv by slaying his older brother, Bali, the king of the monkeys. Even in the scene where Bali castigates his brother and his allies for catching him unawares, a violation of the heroic code, Tulsidas’s positioning of Ram as divine saviour is absolute, as Bali later expresses gratitude for dying at his hand. Such morally ambivalent moments of the epic are brought to life again and again by the translation, leaving them open for interpretation. The mood of bhakti permeates every verse; both Hanuman and Sugriv instantly recognise Ram’s divinity, and the exiled monkey ruler only reluctantly resumes his throne, for he would have renounced the world to worship at Ram’s feet.

A compelling initiation into Indian narrative poetry, mysticism and spirituality

Lutgendorf seamlessly connects 16th century verses with present-day poetry

What follows is a tale made no less interesting by our familiarity with it. In “The Beautiful Quest”, Ram’s alliance with the monkeys initiates the search for Sita’s location and climaxes in Hanuman’s journey to Lanka. This section focuses on the powerful Hanuman, who is worshipped as a god in his own right. Mischievous and playful, Hanuman leaps over the Southern Ocean to Lanka, makes his way into the forest of Ashoka and delivers his lord’s ring to a distraught Sita. His verses assuring Sita of Ram’s love and promises of rescuing her are some of the most moving, powerful lines of Tulsidas’s poem. Equally stunning is the description of Lanka and the terrifying Ravana, whose punishment of Hanuman backfires when the monkey sets the city ablaze with the fire on his tail. This is also when Ravana’s brother Vibhisana defects to Ram’s army, after being moved to devotion by Ram’s benevolence. The last section concludes with Ram’s army’s plan to build a bridge of stone that floats on the seas.

The message of the Ramayana has endured across time — it is the triumph of good over evil, gods over demons, and an ode to a supreme being. Such words as “He whose body is dark as a blue lotus/ and who is more lovely than a billion love gods—/ listen to the litany of his merits—/ whose name is a fowler for the birds of sin” cannot stem from anything but an unshakeable faith in a celestial saviour, a faith powerful enough to transcend ages. Living in Kali Yuga, or the age of evil as it is called, reminders of such faith are reassuring. Lutgendorf’s dexterity with language and its texture is impressive, as he seamlessly connects 16th century verses with present-day poetry, couching an ancient tradition in contemporary poetics. For myth lovers or for those curious about one of the greatest works originating from India, The Sea of Separation is a must-read. It is a compelling initiation into Indian narrative poetry, mysticism and spirituality.