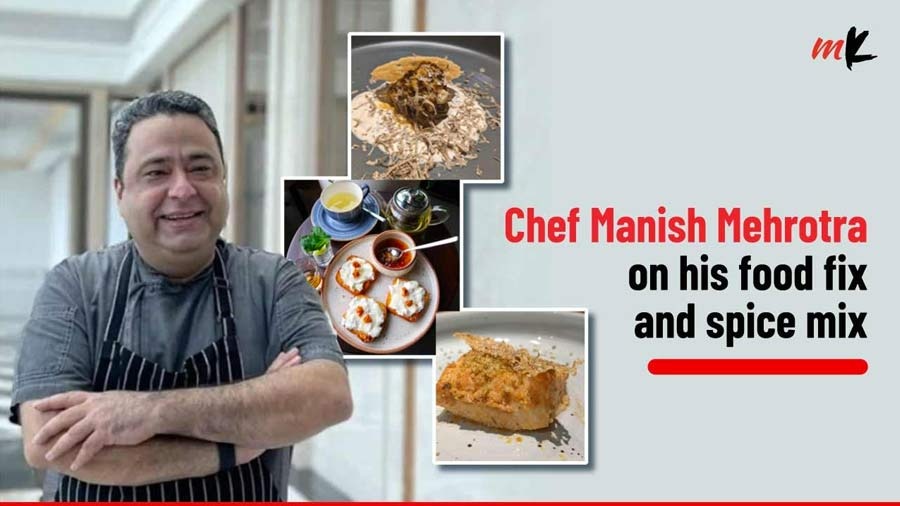

Chef Manish Mehrotra needs no introduction. His restaurant, Indian Accent, has been on the Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants list in the last seven years. He is also the #1 chef in India on the Food Superstars Top 30 Chefs list by Culinary Culture.

Masters of Marriott Bonvoy and Culinary Culture brought Indian Accent to JW Marriott Kolkata for the first time on September 24-25. The two-day event was preceded by an interaction between the celebrated chef and Culinary Culture co-founder Vir Sanghvi. Here are excerpts from the ‘Culinary Conversation’ between the two that celebrate Manish’s journey, his influence on Indian cuisine and Indian chefs, and his love for street food and nostalgia.

Manish’s journey before Indian Accent

Vir: Going to a hotel school was a career decision because you never wanted to run your father’s petrol pump. You were fascinated by the kitchen and you joined the Taj President Hotel. You left and approached people in Delhi for jobs and many people turned you down, including ITC hotels. You then ended up with Rohit Khattar’s company, which was doing the Indian Habitat Center in Delhi. You joined as the chef of Oriental Octopus, a restaurant that was way ahead of its time because it was doing authentic Oriental food at the time when the rest of Delhi was eating Punjabi Chinese. Rohit then suggested that you go to London, to revamp a nightclub called Tamaria, which served Pan-Asian cuisine. You were the chef there when we first met. I wasn’t keen on checking out nightclubs in London but I went because Rohit was a friend. After the meal, I called Rohit and said, “This is the best meal I’ve ever had in London. This man is a genius”.

At this stage, you were not doing Indian food. Later, Rohit informed me that you’d taken over a dining room in a hotel called The Manor in Delhi’s Friends Colony. It was to be an Indian restaurant and you, who had not been an Indian chef till then, would return to India and run the restaurant. It would be called Indian Accent.

You take us through the rest of the journey, Manish.

Accent in New Delhi as it looks today indianaccent.com

Manish: We were supposed to open Indian Accent in November 2008 but the 9-11 attack postponed our plans till March 2009. The restaurant was located inside a residential colony and somehow people would never be able to find it. “Kidhar hai (where is the restaurant?)?” they’d ask. Then, when they’d walk in and learn that we didn’t have things like biryani or kebabs, they’d say, “How can you open an Indian restaurant in Delhi without Butter Chicken?” But we stuck to our guns and did what we were actually trying to do. When I was in London, I saw Indian food in a different avatar. That avatar was missing from India and I wanted to bring it to people here. This was the whole idea behind Indian Accent.

Introducing India to ‘modern Indian cuisine’

Vir: Chefs had tried to do it before but failed. There was a restaurant in that exact dining room run by Vineet Bhatia, which did modern Indian food; and Avijit Saha tried, too.

Manish: Yes, so we started explaining to people what exactly we were trying to do. Foodistan (a professional chef competition on NDTV) also helped create that buzz and slowly the restaurant started becoming popular. It helped that we broke a lot of rules! You see, I was never trained as an Indian chef. I started my career at the Thai Pavilion under chef Ananda Solomon, so I was trained as a Pan-Asian chef. That helped me to convert techniques in Indian food. If somebody said you can make chicken tikka only in a tandoor on a seekh, I disagreed because there are other ways.

Chef Manish set trends by bringing ‘nostalgic’ street food to restaurant menus. “In that era, there was no street food in a restaurant. The notion that you could go to a fancy expensive restaurant to eat phuchka… you would really be laughed at! People would say, ‘Go eat phuchka outside Victoria Memorial, why are you coming to the restaurant?’” said Vir. Indian Accent/ Facebook

Vir: You weren’t trained as an Indian chef, but you weren’t trained as a French chef either. What was happening in London, in those days, was that chefs would take an Indian dish, temper the masala level, get rid of the chillies and would present it on the plane as though it was French food. So because of the French-ification of Indian cuisine, it was food that looked good. Suppose a chef in London was doing a mutton korma, he would probably use high-quality beef instead of the goat we use in India. He’d make the gravy a little thicker and glossier. He’d make sure it’s less spicy. He’d pour it on the bottom of the plate and then put four cubes of beef on it. It was taking existing Indian dishes and changing the way in which it was presented. The difference with Manish’s food and modern Indian food, as it was called then, was that his was not Frenchified. It wasn’t just about any kind of presentation. There was no sense in trying to imitate European food; he developed his own style.

Manish: When people ask, ‘What do you mean by modern Indian food?’ I really don’t understand the term. I am doing traditional Indian food with unique combinations. Hence a Blue Cheese Naan or a Pork Ribs with Meetha Achar. You won’t find two cuisines in one dish on my menu, ever. So you will never find idli with Kashmiri spices or a Paneer Chettinad. There is a lot of street food influence on my menu.

Pork Ribs with Meetha Achar

‘Frenchification’ of Indian food VS ingredients, flavours and techniques

Vir: You were thinking about ingredients and how you can match them. For instance, what does blue cheese have in common with naan? But you made it work. You shared the example of Gujarati sweet achar and pork ribs, which were probably imported Chilean ribs in those days. Who would have thought of merging those things together? So what you were doing, in a sense, was not looking at Indian food and saying, ‘How can I tweak this dish?’ You were looking at ingredients and at flavours and using your skills and Indian techniques to try and create something. But even with techniques, you were not a slave to some catering college idea of chicken tikka. You were willing to do different things.

Manish: When I see my early menus from 13 years ago, I realise I have also evolved and learnt a lot. My first menu used to have a Chyawanprash Cheesecake and we used to do it with Badam Doodh!

Vir: I think it’s fair to say not everything worked (laughs)!

Manish: There were dishes like Dodha Barfi Treacle Tart, which were an instant hit. Dodha barfi is basically a Diwali-centric barfi made in Punjab and Rajasthan. It’s a hardcore barfi with wheat, coconut, sugar, lots of ghee and dry fruit. When I tasted the treacle tart (British dessert), I thought why not make a treacle tart from dodha barfi?

Of street food and nostalgia

Vir: There are two things you introduced to Indian food — one is street food and the other is nostalgia. Tell us more about those.

Manish: Everybody misses their childhood. So the idea was to create dishes that would make us nostalgic and in a way help that memory to linger and pass on to the next generation. I have a 15-year-old daughter and she is keen to know about the things I ate in my childhood — be it a popsicle, chaat, kulfi or churan. I still remember we used to get our churan from Kolkata, a company called Chamria. Then there are a lot of nostalgia-ridden dishes on my menu like Daulat ki Chaat, Old Monk Rum Ball, Besan Ladoo and Haji Ali-inspired Custard Apple Cream (because we were in Dadar Catering College and we used to take a bike and go to Haji Ali to eat that). I use besan as the base for my cheesecake because it is associated with the childhood memory of friends bringing besan ladoos from home in the hostels we stayed in.

Old Monk Rum Ball and Daulat ki Chaat

Vir: At what stage do you think Indian food is at now?

Manish: We are moving down the right path. There are a few things that worry me, especially in Delhi, like whenever we are moving towards only multi-cuisine restaurants because whatever is opening is serving pizza, sushi, momos and butter chicken.

And my biggest nightmare is Papdi Chaat with mayonnaise! In the last five years, the amount of mayonnaise we have started in everything, even samosa, is really worrying.

The good thing is that ‘real Indian food’ is moving forward and people are becoming aware that it’s not only about naan and curry. Chefs like Gaggan Anand, chef Vineet Bhatia, or New York’s Chintan Pandya, are doing Indian food the right way.

India has many talented chefs, like Avinash Martin, who are not only doing modern Indian food but also taking regional food and upgrading it.

I believe that Indian food used to be slightly intimidating. People outside India were afraid to eat or cook that cuisine in their house. And until the time people do not relate to our food, the cuisine will not move forward. This is now changing. People are trying Indian food at home and learning that it doesn’t have to be spicy, and that it’s not only about curry and rice or naan.

A melting pot of influence

Vir: How are today’s chefs different from your generation?

Manish: They are fantastic. Chefs like Himanshu (Saini), Saurabh (Udinia) and Prateek (Sadhu) are researching and finding out old recipes. We don’t have to invent recipes, we just have to explore India and we find thousands of recipes which are worthy of being served in a great restaurant.

Vir: In France, in the ’30s and ’40s, there was a chef named Fernand Point, who ran a restaurant called La Pyramid and all the chefs who worked with him took his style of cooking and created what ultimately became the nouvelle cuisine. When I look at the scene in India, I see a somewhat similar situation. Farzi Cafe was started by two chefs who worked in Indian Accent. The most successful Indian restaurant in the Middle East at the moment is Tresind and is run by a chef who worked in Indian Accent (Himanshu Saini). One of the most successful and popular Indian restaurants in Singapore is called Revolver, also run by a chef who used to work at Indian Accent (Saurabh Udinia). There are other restaurants I won’t name, which are not necessarily run by chefs who worked at Indian Accent, but have pretty much plagiarised it. Do you think you’re getting to that stage where your influence now extends beyond your own restaurant because your chefs have gone forth?

Manish: It feels good to see that chefs who started under you are now carving their own path. When Himanshu’s restaurant got a Michelin star, he called me first saying, “Chef, ashirwad dijiye.” I don't have a Michelin star and I have had restaurants in London and New York but these guys, whether it is Himanshu or Sourabh, they are doing so well and I couldn’t be happier for them.

Vir: But more than individuals doing well, they have taken forward your philosophy, techniques, and in many cases, your dishes.

Manish: That happens sometimes because the restaurant owners want that from the chefs. Honestly we’ve done so many different dishes in the last 13 years that there’s enough for everyone. At Comorin, too, I see entire teams from hotel chains ordering everything from the menu, and then suddenly I start Comorin dishes on restaurant menus. For example, we were the first one to serve Cheeni Malai Toast in a restaurant in Delhi, which was inspired from Kolkata, and now it’s on other menus. I look at it this way — until the time Indian food is moving forward, there’s nothing wrong.

It’s a learning curve for India’s best chef

Vir: Do you ever wonder because you’ve been so influential early in your career and 13 years later you’re still the best chef in India — that you won’t be able to keep this up? Keep creating new dishes?

Manish: Every time I plan my chef-tasting menu, I think, “This is it. I’ve given it my all, now I can’t do it anymore”. But two months later, there’s a new tasting menu. I keep on researching and I’m a great believer in books. I use the internet only for a little bit of research, but the real knowledge comes from books.

Chef Manish at work

Vir: Many great chefs have access to the best ingredients and therefore can do things differently. But you’ve done well with cheap ingredients. I remember, you used to use Basa, this horrible, mass-produced farm fish, and you turned out a great dish with that.

Manish: We’re still doing that dish but with a cod now. I tried to use other fish but Delhi is a bit particular. The fish should be boneless. It should be without the skin. And it should not smell fishy. So only the Basa seemed to work! As soon as the smell of fish was there, I’d hear, ‘Fresh nahin hai’. If you think about using sardines, you’re finished! I used Basa in that particular dish like paneer — as a flavour carrier.

Vir: Most of us have mattar (peas) at home and are used to it. But you use the sweet petits pois, which is very unusual for an Indian chef. Where does that come from?

Manish: I tasted those peas for the first time in a restaurant in Amaya (a Michelin-starred restaurant in London). When we use it, it carries so well. It works very well.

Vir: Is it true that for the New York Indian Accent, you used to import Tata Salt?

Manish: It’s true! The salt there… how can I put it… the salt was not salty! If you added more, it changed the flavour. And not just Tata Salt, I even asked for Amul Butter!