The words ‘academic’ and ‘superstar’ do not usually belong in the same sentence. But if an exception were to be made, then Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak — literary theorist, feminist critic and one of the world's foremost postcolonial thinkers — would be the ideal candidate to exemplify both these nouns.

In a career spanning close to six decades, Spivak, whose trademark attire of sari paired with combat boots would create quite a stir back in the day, has not just transformed the largely impermeable world of critical theory. She has done so with gusto, and a characteristic insouciance, that brought her acclaim far beyond seminar rooms and university auditoriums.

Spivak, who turned 80 this February, was present at the recently concluded Kolkata Literature Festival (KLF) on the grounds of the 45th International Kolkata Book Fair, where she was felicitated and requested to deliver a keynote lecture. My Kolkata was there during her entire stay of a couple of hours at KLF on a late spring afternoon to listen intently to what Spivak had to say and quiz her further on her incredible career.

From deconstructing her own keynote to delving into Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction, from reflecting on the changing nature of books to recollecting her experience of translating Mahasweta Devi, Spivak was as engaging and illuminating as ever. Highlights from her address as well as her interaction with My Kolkata follow.

‘Translating Mahasweta Devi was completely unlike translating Derrida’

Spivak was asked to translate Mahasweta Devi’s works by Ranajit Guha TT archives

For those who think that the passage of years blunts a person’s rebellious edge, Spivak would come across as an aberration. Indeed, a few hours with her would surely have disabused them of such notions.

Historian Ranajit Guha had asked Spivak to make Mahasweta Devi accessible to readers in English. Spivak was renowned internationally for translating Jacques Derrida’s Of Grammatology (from French), for which she wrote an iconic (and seemingly never-ending) translator’s preface. Who better than her to take the works of the Jnanpith Award winner and a fellow Bengali to the world? Spivak, however, was not too keen.

“I don’t like to do things when I’m told to do them. Ranajit da told me to translate Draupadi and he was a bit insistent,” Spivak recalled, as if she was still annoyed that she had agreed.

What was it like translating the works of Mahasweta Devi?

“Translating is the most intimate activity and Mahasweta di liked my translation of Standayini. She told me that my writing made her feel like she was reading her own Bengali, which blew me away,” Spivak said.

How different was it to translate Mahasweta Devi after trying to explain the deftness of Derrida’s deconstruction in English? “It was completely unlike translating Derrida. He was in my field, even though I didn’t know him personally (Spivak only met Derrida in 1971, about four years after translating his work). But people resisted the fact that I was translating Derrida; they thought I was ruining my career. Whereas with Mahasweta Devi, everyone was asking me to translate her,” Spivak replied.

‘I didn’t miss out on the Eurocentrism in Derrida’

Notwithstanding the resistance she faced, translating Derrida became the turning point of Spivak’s career, if not as an academic, then definitely as a public figure. But setting the recognition and adulation aside, My Kolkata tried to probe Spivak on how she had evaluated her translation with reference to Derrida’s original work over time? Had she, for instance, missed out on Derrida’s Eurocentrism — basically the worldview that assumes the West’s superiority — only to detect it much later?

Spivak’s answer was emphatic, both as a personal clarification and rectification. “I didn’t miss out on the Eurocentrism, I missed out on the critique of Eurocentrism,” she clarified, a tad annoyed that her lacuna had not been identified precisely enough.

“Please be aware that Derrida, right from his time in Algeria, was strongly critical of Eurocentrism and first used the word ‘Eurocentrism’ in 1967. It was difficult to find that word back then. Additionally, I wasn’t at all aware of the delicacy of his analysis of informatics (no, she wasn’t interrupted to explain what that meant). He was so ahead of his time.”

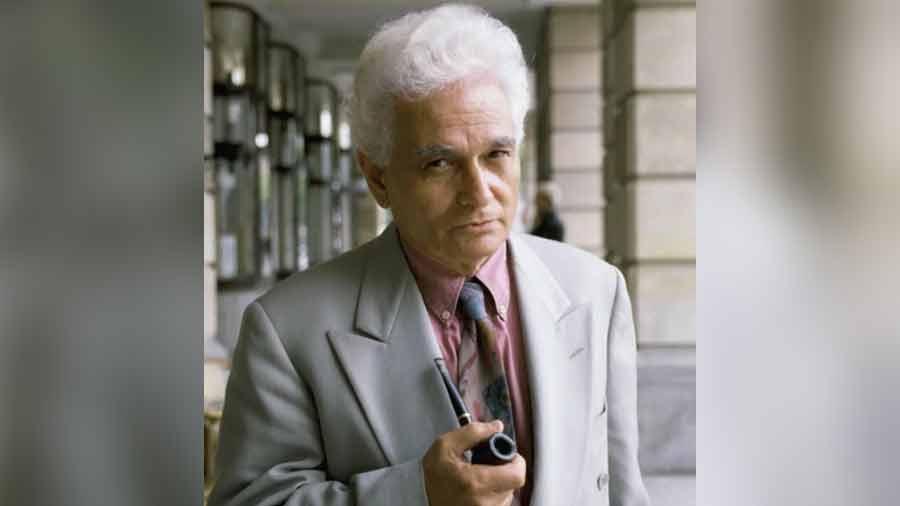

Spivak’s translation of Derrida not only made her famous but also made the French philosopher accessible to English readers TT archives

Content with her answer, which seemed to have improved her mood somewhat, Spivak added with a semi-snigger that “at that point, I didn’t really know any Hegel either. The introduction (the one she wrote) has no Hegel, which is bad. But I’ve tried to educate myself to be equal to the book.”

‘I don’t know what my talk is going to be about’

At KLF, Spivak, as expected, was more than equal to her audience. Her keynote was billed as being on books, thoughts and language, a brief so deliciously vague that someone of Spivak’s academic pedigree could have spoken for the whole day. Instead, she took just over 15 minutes, before opening the floor to questions.

Before the talk, Spivak chatted with familiar faces at the author’s lounge, where we dared to ask her what she was going to discuss on stage. “I don’t know what my talk today is going to be about. I couldn’t know the answer to this question and I doubt that anyone could,” was her inimitable response.

Spivak’s keynote at KLF was on books, thought and language Arijit Sen

Over the decades, Spivak has been criticised for her “excessively elliptical prose”, which makes her “so bewilderingly eclectic” as to be “pretentiously opaque” (in the words of literary theorists Stephen Howe and Terry Eagleton). Simultaneously, she has also been credited by good friend and feminist critic Judith Butler for inspiring and changing the thinking of “tens of thousands of activists and scholars”.

‘The nature of the book has changed profoundly’

When she eventually delivered her keynote at KLF, Spivak did not attempt to be esoteric. Nor did she try to change how people thought. Claiming to “avoid giving a keynote as I’m giving a keynote” (try deconstructing that!), Spivak mostly shared anecdotes for the first part of her talk. From joking about how she was concerned not to set the place on fire and emulate Derrida (from 1997) to outlining her long association with the Book Fair since her days as a “young, politicised individual”, there was a clear geniality to Spivak’s first few minutes on stage. Thereafter, she transitioned, tackling the subject of her talk head on, opening with the statement that “the nature of the book as an object has changed profoundly”.

“Today, the world is so divided into race, caste, gender and class that what the book means depends very much on those divisions, too,” she said.

“My father’s mother, a very smart woman, could read a little, but she couldn’t write. From her point of view, there was no such thing as a book. Nowadays there’s a profusion of books, which has brought about an upward class mobility. When I compare myself to my father’s mother, I can see myself to be from a different class, maybe a different race, too,” she continued, designating the “different race” part as worthy of elaboration on another day.

Could a change in the nature of the book also be a factor in how the humanities are perceived around the world, with many arguing that the humanities are in crisis?

“No, I don’t believe that the humanities are in crisis,” Spivak asserted. “The humanities are self-trivialised, this is something that’s happening everywhere and at all levels.”

‘I won’t use PDFs’

Spivak urged the audience at KLF to imagine a world where there would be no books

Speaking about the bhadralok culture in West Bengal and how, even to this day, there remains “a small intellectually elite group (among Bengalis) that really cares about books”, Spivak acknowledged that we must be able to imagine a time when there are no books. A time when “people don’t know how to read or write… (and consequently) don’t know how to vote”.

The next point that Spivak raised in her speech addressed a pertinent concern of contemporary readers: how to retain a special relationship with physical books in an age of digital copies, or, as Spivak called them (not without an undercurrent of derision), “PDFs”?

“I tell my students at Columbia University that I won’t use PDFs. I want them to hold the books in their hands and to write and annotate on the pages of the books. I don’t want students to blank after my course, and that can happen when you don’t rely on physical books,” she explained.

A student from the audience challenged Spivak’s argument, questioning how youngsters who were yet to earn for themselves could be expected to buy large, expensive books instead of downloading free PDFs. “You don’t look particularly poor to me. When I look at young middle class women, I feel like telling them that rather than spending money on jewellery, please spend money on books. Moreover, a number of my books have been republished by Indian publishers and aren’t all that expensive. You can try those out,” Spivak said, to a roar of approval.

‘Literature can’t make a truth claim’

Spivak was relatively happier with the subsequent interjection from the audience, which posed the question of whether books were changing the way we love. Spivak partially agreed, before proceeding to analyse how “books aren’t just instruments of learning, for the literary is something that learns from the singular and the unverifiable”.

Towards the end of her keynote, Spivak differentiated between ‘mere learning’ and ‘literary learning’

“This is why most books, especially literature, can’t make a truth claim,” she said. “Our imagination is neither rational nor irrational, and yet the way it perceives books can be said to come from a place of something called love.”

Finally, as part of her concluding insights, Spivak urged readers to differentiate between “mere learning” and “literary learning” wherein the former only allows one “to control the text” while the latter lets one “surrender oneself to the text”.

“The literary exists so that we can go towards it,” she summed up, demonstrating with aplomb how she endures as a repository of constantly compelling wisdom. Or rather, to use her own words, someone who is “a bad teacher, but a serious one”.