Jazz, as we all know, is the art of blending diverse elements to create a harmonious whole — a concept that perfectly embodies The Native Quartet’s formation and mission. Dedicated to advancing the Native Jazz movement, the group seamlessly merges tradition and innovation, with an aim to engage audiences across national and international stages. By weaving cultural narratives into their performances, they often create a powerful dialogue that resonates with people of all ages and backgrounds.

The quartet, featuring Delbert Dale Anderson (trumpet), Edward William Littlefield II (percussion), Michael Bartholomew Glynn (double bass), and Reuel Vallester Lubag (pianist/drummer), performed at the Calcutta School of Music on Sunny Park on a crisp December evening. Their performance focused on jazz interpretations of traditional native songs, each accompanied by a cultural story and sung in their native languages. Adding a touch of authenticity, alongside classic jazz instruments, Edward William Littlefield II integrated native percussion into the set.

Brought to the city by Prayasam and the American Center Kolkata, the band also engaged in a lively interactive session with My Kolkata before the performance. Edited excerpts follow...

My Kolkata: Could you elaborate on the concept of the Native Jazz Quartet? How did the idea of blending native/folk melodies with jazz come about?

Edward William Littlefield II: When we started, it was a motley group — Reuel, myself, Jason Marsalis (African-American), and Christian Fabian (Swedish-German). I wanted to showcase my Tlingit heritage, while Reuel shared his native folk songs. Jason brought African-American melodies from New Orleans, and Christian contributed 250-year-old melodies from his ancestors. Our goal was to perform the songs our ancestors created — beginning with Tlingit melodies.

What is the mission behind the Native Jazz movement, and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Littlefield: This mission is too personal for me. With only seven fluent Tlingit speakers left, sharing the language worldwide is my passion. As the only Tlingit jazz musician I know, I aim to engage people with my culture and help preserve it.

Delbert Dale Anderson: My elders in the Diné (Navajo) heritage have recently become more open to sharing our culture. When I first blended traditional chants with funk and hip-hop, I was unsure if it was appropriate. My elders explained that, while they would have opposed it years ago, they now believe preserving our culture through music could inspire the younger generation to reconnect with it.

How do you select and arrange native melodies for jazz, given that your music is based on the swing/bebop tradition?

Littlefield: I’m inspired by jazz masters like Benny Golson. For example, our Tlingit song Haat Yee Aadéi is thousands of years old, and while arranging it, I adapted Golson’s Killer Joe to fit the Tlingit melody. I often have conceptual melodies in mind, and Reuel helps develop them with me. That’s how we collaborate.

Michael Bartholomew Glynn: Older folk tunes are versatile and often suggest their own arrangement. Like we performed an Irish piano tune with a gospel-inspired arrangement, because I felt it would suit the piece beautifully.

Can you share a memorable example of audience interaction from your performances, which often turn into ‘cultural stories’?

Anderson: Recently, at the Hornbill Festival, I shared a story about a healing landscape and played a simple piece — just one repeated note. The audience clapped after each note, responding more emotionally than I’ve experienced in the US. Later, people told me they could feel and understand what I was expressing about the place.

Was it challenging to adapt your native music into jazz, given your diverse backgrounds?

Anderson: Jazz naturally brings cultures together, so collaboration happened easily. Like Congo Square, the birthplace of jazz, our band shares diverse traditions. Each member contributes songs from their culture, blending them respectfully. Personally, I avoid performing prayers or sacred songs to honour cultural boundaries. While many bands stick exclusively to jazz or jazz standards, we focus on blending these traditions in a way that’s both safe and respectful.

The Native Jazz Quartet performing at Calcutta School of Music

Reuel Vallester Lubag: It’s all about living in the moment. You might play the same song two days in a row, but each time, it feels like a different song. That’s because the audience has such an impact on us — the more they enjoy the performance, the more we enjoy playing.

How do you see your work contributing to cross-cultural understanding through jazz?

Lubag: For me, it feels completely natural. When I first started playing music, one of the earliest albums I remember listening to was Ambassador Satch by Louis Armstrong, followed by works from Benny Goodman and others. These musicians shared their culture while interacting with others, and that’s the essence of jazz. We’re striving to build bridges. People often discuss diplomacy, but at its core, it’s really about sharing.

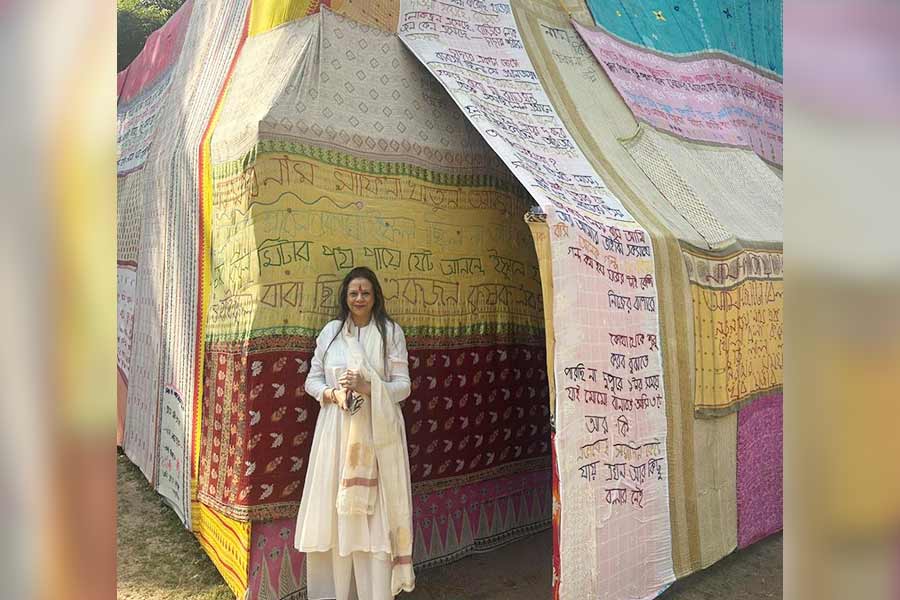

Juan Clar, deputy director, American Center Kolkata and Chaitali Ganguly, principal, Calcutta School of Music facilitated the band members before the show

How has touring and performing at international festivals influenced your music and collaboration?

Anderson: Touring internationally has greatly influenced my music. In Johannesburg, South Africa, we created an album with Zulu and San artistes whose unique harmonies deeply moved me. Their contributions inspired me to incorporate such harmonies into my playing. Experiences like these shape how I approach music and collaboration.