Everybody writes to the Colonel. The man, an elegant six-foot-something Sikh pushing 50, is flooded with letters from families, friends, relatives, commanding officers and most of all family, friends and relatives of patients. They write to him, telephone him, signal him because they know he is stationed near a town and because he is an expert.

Colonel Harry (name changed on request) is doctor at the highest altitude army hospital in the world. “It’s not funny, is it?” he guffaws, “that your welcome to a warzone should be from the Life Insurance Corporation.”

He is referring to a giant banner just outside Leh airport that reads: “Welcome to 11,800 feet above mean sea level.” The penumbra touches you short of Leh when the cabin crew in the Airbus A320 in mid-air ensures that all window shutters are pulled down.

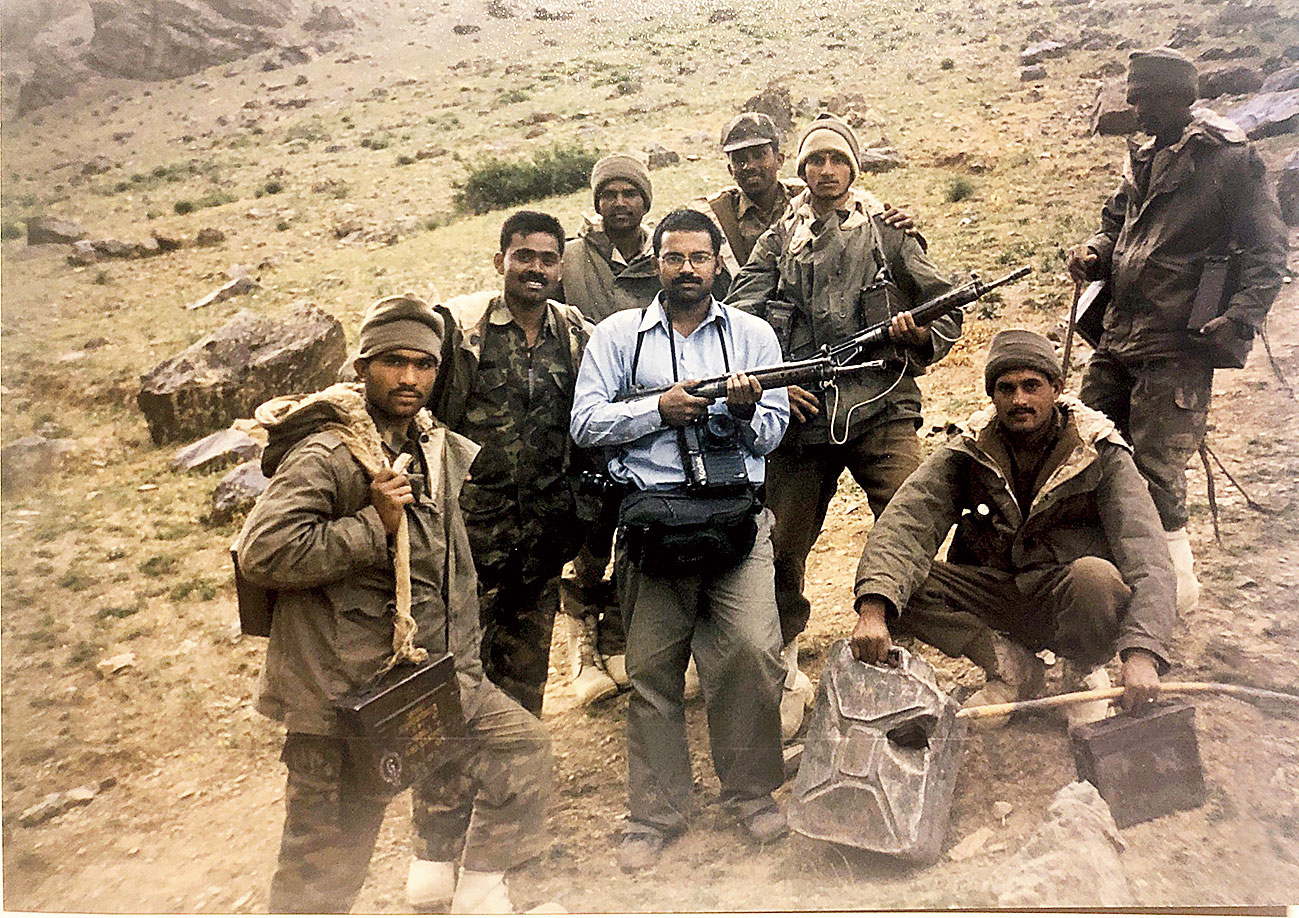

The plane is probably being escorted by an IAF fighter. Also, civilians are not meant to see the military installations on the ground. In the event, you miss out on some of the breathtaking sights of the icy Himalayas. Across the battlefront along the LoC, Col Harry’s advice is sought to decide troop deployment.

He is the Number 1 specialist on the effect of high altitude on the human body. “There is no alternative to acclimatisation,” he explains. At mean sea level, atmospheric pressure is 760mm, the concentration of oxygen in the air an average 21 per cent. Here, at 12,000 feet, pressure is 560mm, oxygen concentration 17 to 18 per cent. At 14,000 feet, oxygen level is between 14.5 and 15.5 per cent. At 17,000, it is 12.5 to 13 per cent.

Beyond 18,000 feet, it does not matter because the body does not acclimatise. High altitude-associated problems are more acute here in Ladakh because there is hardly any tree cover and consequently oxygen concentration is poorer.

So Dr Harry insists that as far as possible, fresh troops being moved here must be from comparable heights as in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

His 210-bed hospital services the Kargil, Drass, Batalik and Siachen sectors. The Colonel is interrupted by a telephone call. It is from somewhere in the Drass sector.

“Hello... Hello... Yes, I understand... You do this if you have an MO (medical officer) in one post, move the nursing staff to another...” His resources, clearly, are stretched. He could do with more doctors, nurses, medicine, more of practically everything. Shortages have meant that his job is as much about treating patients as about managing them.

“In war, there will be casualties,” he says and speaks the official line. “We are up to the situation.” He reels off no statistics. “I am sorry, I can’t give you hard information.”

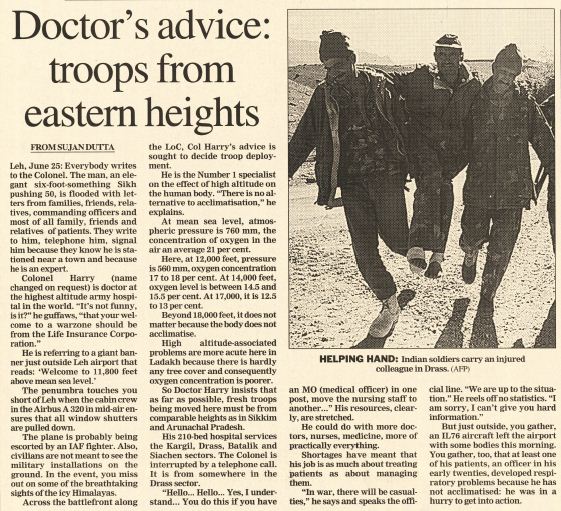

But just outside, you gather, an IL76 aircraft left the airport with some bodies this morning. You gather, too, that at least one of his patients, an officer in his early twenties, developed respiratory problems because he has not acclimatised: he was in a hurry to get into action.

Sujan Dutta in Leh

This story was first published in The Telegraph in 1999